Even consciousness could reveal its secrets someday with this realistic simulation, researchers hope. It will not only provide an inner window on brain disorders, but may become sophisticated enough to mimic the human brain’s full complexity.

Frequent tanning bed users may have up to an eight times greater risk for melanoma than people considered at high risk for melanoma who don’t use tanning beds, according to a new study that also showed how tanning beds alter melanoma-linked DNA on the molecular level and damage areas of skin not usually exposed to the sun.

A case-control cohort study of patients considered at high risk for melanoma finds that tanning bed users have higher rates of melanoma and disease with significantly more mutations.

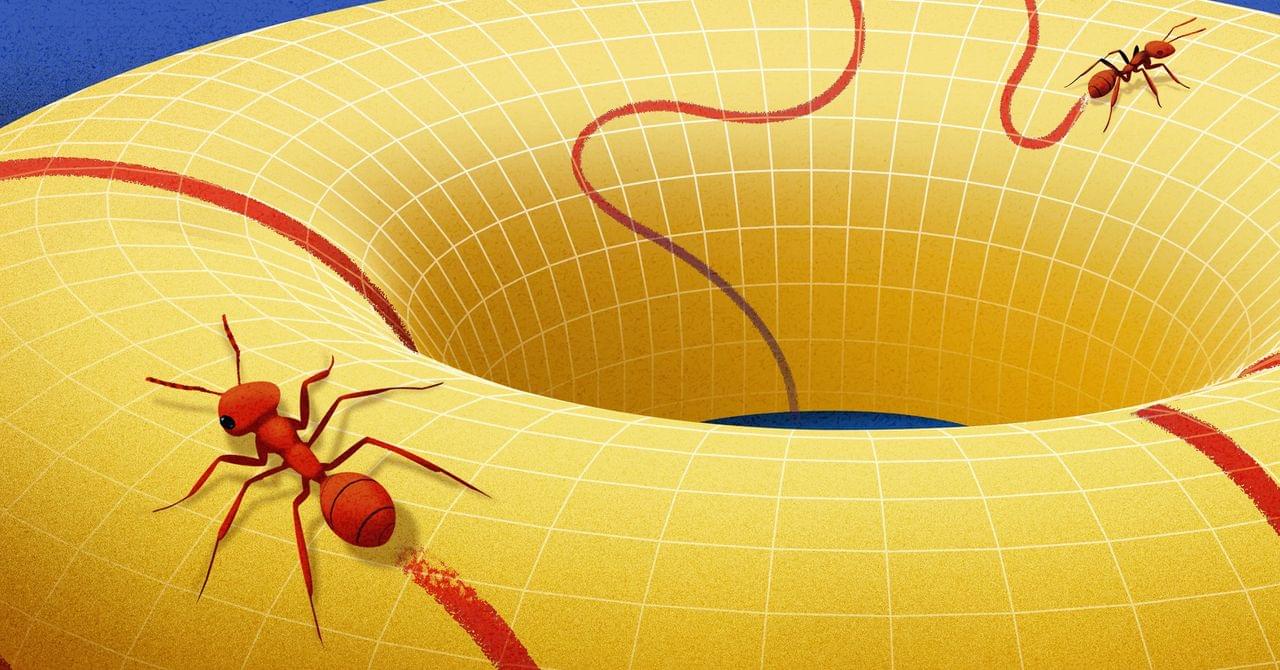

The world is full of such shapes—ones that look flat to an ant living on them, even though they might have a more complicated global structure. Mathematicians call these shapes manifolds. Introduced by Bernhard Riemann in the mid-19th century, manifolds transformed how mathematicians think about space. It was no longer just a physical setting for other mathematical objects, but rather an abstract, well-defined object worth studying in its own right.

This new perspective allowed mathematicians to rigorously explore higher-dimensional spaces—leading to the birth of modern topology, a field dedicated to the study of mathematical spaces like manifolds. Manifolds have also come to occupy a central role in fields such as geometry, dynamical systems, data analysis, and physics.

The masses of fundamental particles such as the Z and W bosons could have arisen from the twisted geometry of hidden dimensions, a new theoretical paper has demonstrated.

The work has outlined a way to bypass the Higgs field as the source of particle masses, offering a new tool for understanding how the Higgs field itself might have emerged, as well as a possible means of addressing some of the persistent gaps in the Standard Model of particle physics.

“In our picture,” says theoretical physicist Richard Pinčák of the Slovak Academy of Sciences, “matter emerges from the resistance of geometry itself, not from an external field.”

In collisions at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider, hotter than the Sun’s core by a staggering margin, scientists have finally solved a long-standing mystery: how delicate particles like deuterons and their antimatter twins can exist at all. Instead of forming in the initial chaos, these fragile nuclei are born later, when the fireball cools, from the decay of ultra-short-lived, high-energy particles.

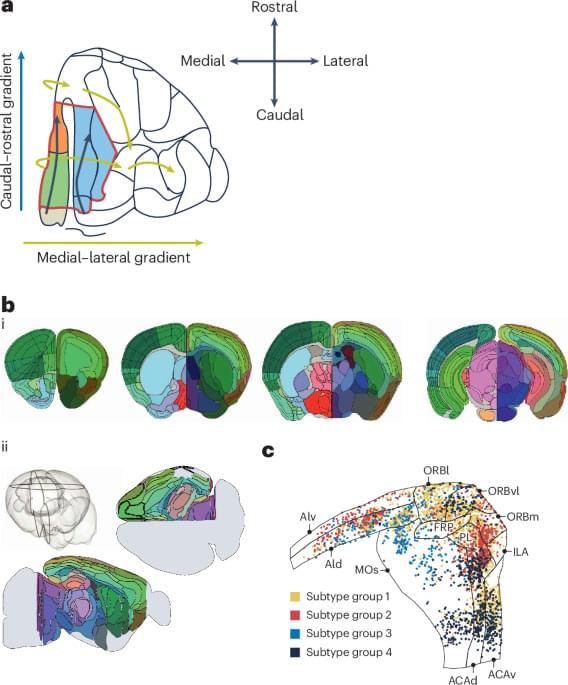

For decades, neuroscience textbooks have taught us that the brain is organized into discrete areas — like Broca’s area for language or V1 for early vision, each with a well-defined role. This kind of areal parcellation has shaped how we interpret brain imaging, neural recordings, and even theories of cognition.

But this new article challenges that foundational idea. Instead of treating brain areas as the central units of brain function, the authors argue that brain organization is more complex, multi-layered, and distributed than traditional area-based frameworks suggest.

The authors begin with a simple observation: the ways in which neuroscientists define cortical areas, based on cell structure (cytoarchitecture), connectivity, or response properties — don’t always point to the same boundaries. In other words, different methods of dividing the cortex produce different “maps,” and there’s surprisingly little convergence on a single, definitive set of brain areas.

This inconsistency raises a big question: If areas aren’t consistently defined by structure or connectivity, can we really treat them as the fundamental units of brain function.

Parcellation of the cortex into functionally modular brain areas is foundational to neuroscience. Here, Hayden, Heilbronner and Yoo question the central status of brain areas in neuroscience from the perspectives of neuroanatomy and electrophysiology and propose an alternative approach.

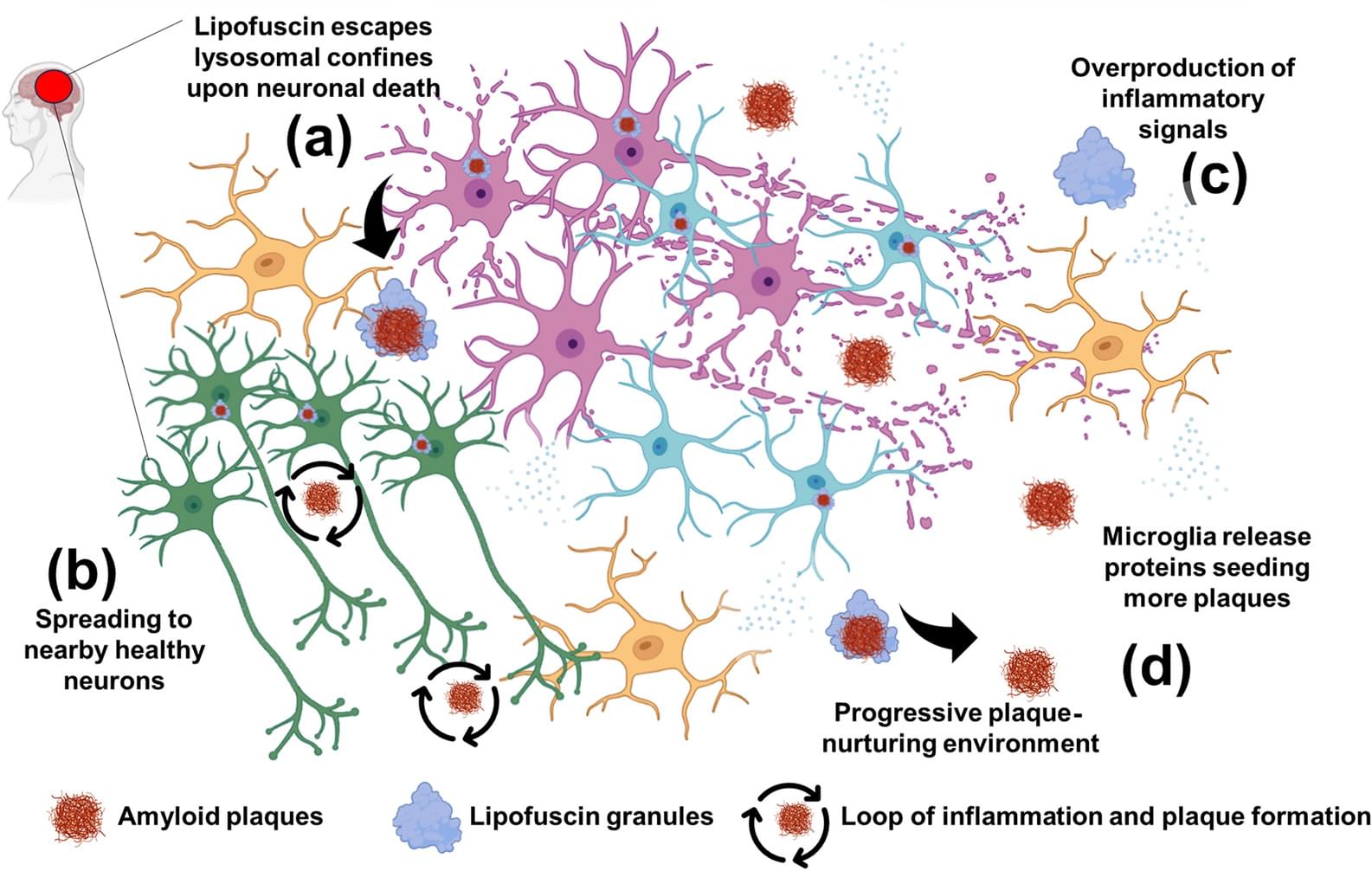

Lipofuscin, a marker of aging, is the accumulation of autofluorescent granules within microglia and postmitotic cells such as neurons. Lipofuscin has traditionally been regarded as an inert byproduct of cellular degradation. However, recent findings suggest that lipofuscin may play a role in modulating age-related neurodegenerative processes, and several questions remain unanswered. For instance, why do lipofuscin granules accumulate preferentially in aged neurons and microglia? What happens to these pigments upon neuronal demise? Particularly in neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s disease (AD), why does amyloid β (Aβ) deposition usually begin in late adulthood or during aging? Why do lipofuscin and amyloid plaques appear preferentially in grey matter and rarely in white matter? In this review, we argue that lipofuscin should be revisited not as a simple biomarker of aging, but as a potential modulator of neurodegenerative diseases. We synthesize emerging evidence linking lipofuscin to lysosomal dysfunction, oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation and disease onset—mechanisms critically implicated in neurodegeneration. We also explore the potential interactions of lipofuscin with Aβ and their spatial location, and summarize evidence showing that lipofuscin may influence disease progression via feedback loops affecting cellular clearance and inflammation. Finally, we propose future research directions toward better understanding of the mechanisms of lipofuscin accumulation and improved lysosomal waste clearance in aging.