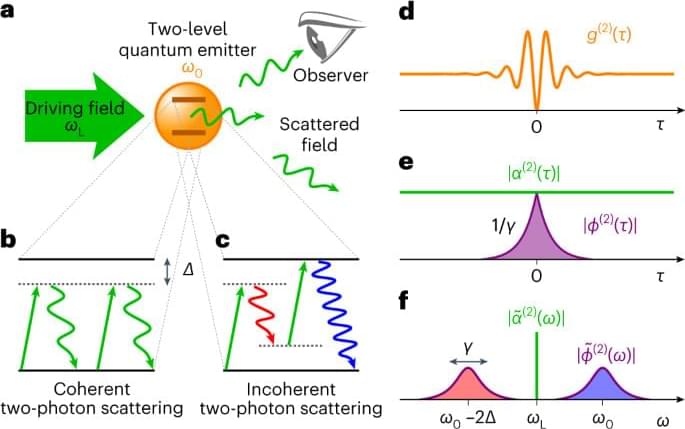

To tackle the problem, the LIGO Scientific Collaboration followed an approach, proposed in 2001, that involves squeezing the noise ellipse differently at different frequencies. This frequency-dependent squeezing is realized by coupling the interferometer to a 300-m-long “filter” cavity. Through the cavity, the team could tailor the spectrum of the squeezed state, injecting amplitude squeezing in the low-frequency region and phase squeezing in the high-frequency region, says Victoria Xu, also of MIT LIGO Lab. “This [approach] allows us to reduce the limiting forms of quantum noise in each frequency band,” she says.

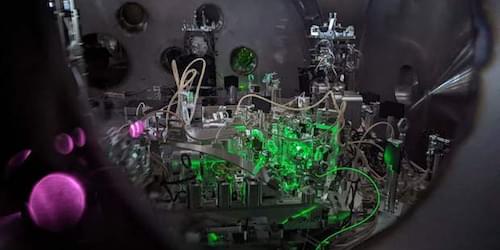

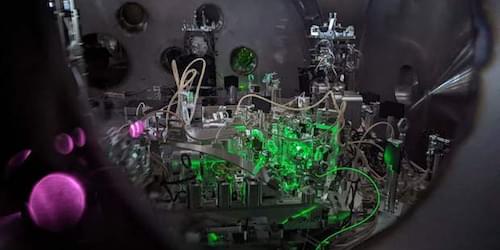

The frequency-dependent approach had previously been demonstrated in tabletop systems but implementing it to mitigate radiation-pressure noise in a full-scale gravitational-wave detector was a massive engineering challenge, Xu says. An important aspect was the minimization of optical losses due to imperfect optical components or to a mismatch of the light modes propagating in the various parts of the setup—the filter cavity, the squeezer, and the interferometer. “Any loss can be seen as a ‘port’ through which regular, nonsqueezed vacuum can enter,” Barsotti says.

The LIGO Scientific Collaboration tested frequency-dependent squeezing during the commissioning of the instrument upgrades for the fourth run, comparing detector noise spectra for no squeezing, frequency-independent squeezing, and frequency-dependent squeezing. Frequency-dependent squeezing yielded similar enhancements to frequency-independent squeezing at high frequencies while eliminating the degradation below 300 Hz due to radiation-pressure noise. The team estimated that the improved noise performance would increase the distance over which mergers can be detected by 15%–18%, corresponding to up to a 65% increase in the volume of the Universe that the LIGO interferometer will be able to probe. Quantum optics specialist Haixing Miao of Tsinghua University in China says this result demonstrates an exceptional ability to manipulate quantum states of light with optical cavities but also offers an impressive demonstration that quantum measurement theory applies to the kilometer scales of a gravitational-wave detector.