A first-ever stretchy electronic skin could equip robots and other devices with the same softness and touch sensitivity as human skin, opening up new possibilities to perform tasks that require a great deal of precision and control of force.

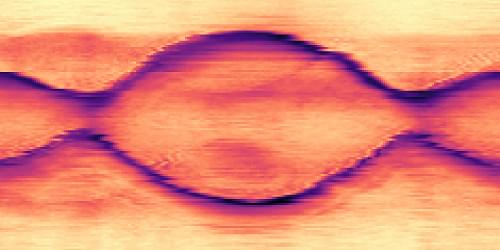

A proposed experiment could bring scientists closer to answering the long-standing question of whether gravity is a classical or a quantum phenomenon.

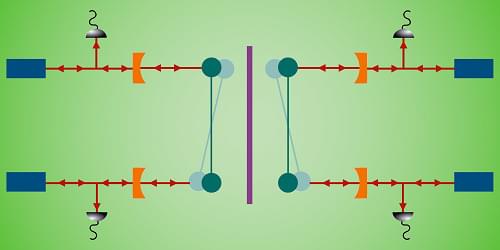

A method for freely adjusting the parameters of a loop of optical fiber enables the exploration of exotic topological phases of matter.

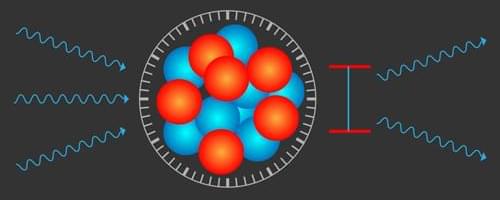

Researchers use a laser to excite and precisely measure a long-sought exotic nuclear state, paving the way for precise timekeeping and ultrasensitive quantum sensing.

Any reliably produced, periodic phenomenon—from the swing of a pendulum to the vibrations of a single atom—can form the basis of a clock. Today’s most precise timekeeping is based on extremely narrow electronic transitions in atoms, which resonate at optical frequencies. These stupendously precise optical atomic clocks lose just 1 second (s) in about 30 billion years. However, they could potentially be outperformed by a nuclear clock, which would instead “tick” to the resonant frequency of a transition that occurs in the atomic nucleus instead of in the electronic shell. The most promising candidate for this nuclear standard is an exceptionally low-energy and long-lived excited state, or isomer, of the isotope thorium-229 (229 Th). Researchers have now achieved the long-sought goal of exciting this transition with ultraviolet light.

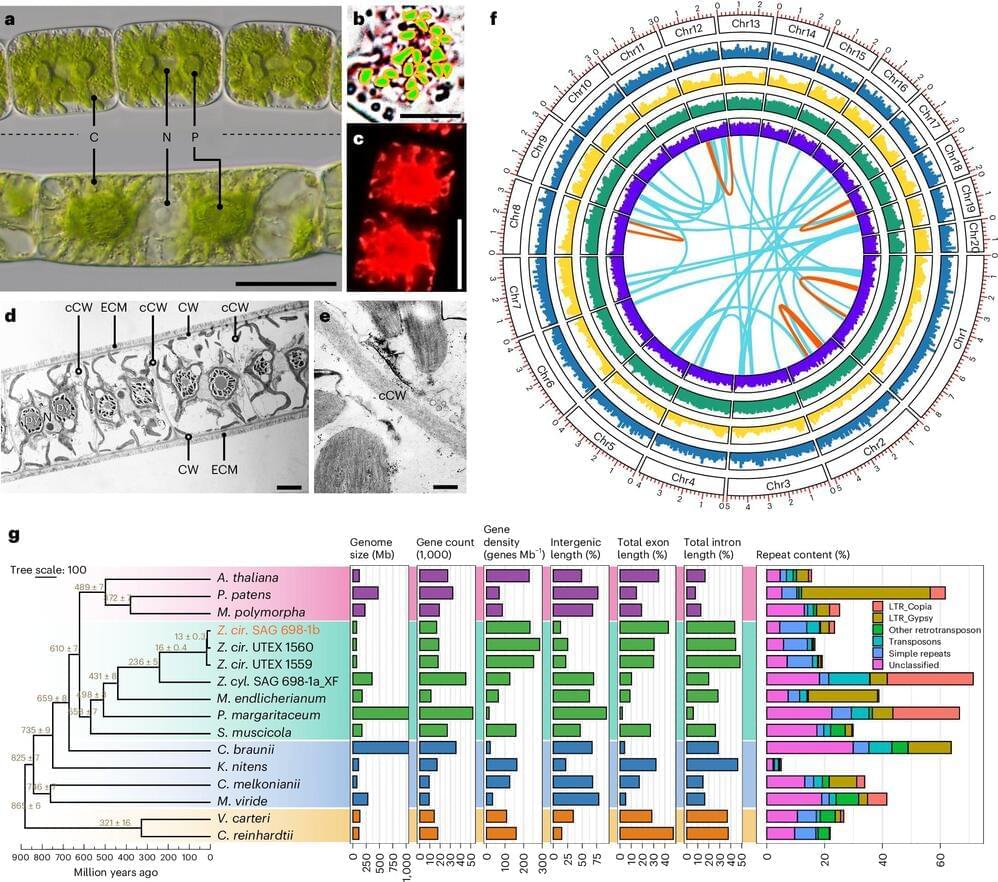

Plant life first emerged on land about 550 million years ago, and an international research team co-led by University of Nebraska–Lincoln computational biologist Yanbin Yin has cracked the genomic code of its humble beginnings, which made possible all other terrestrial life on Earth, including humans.

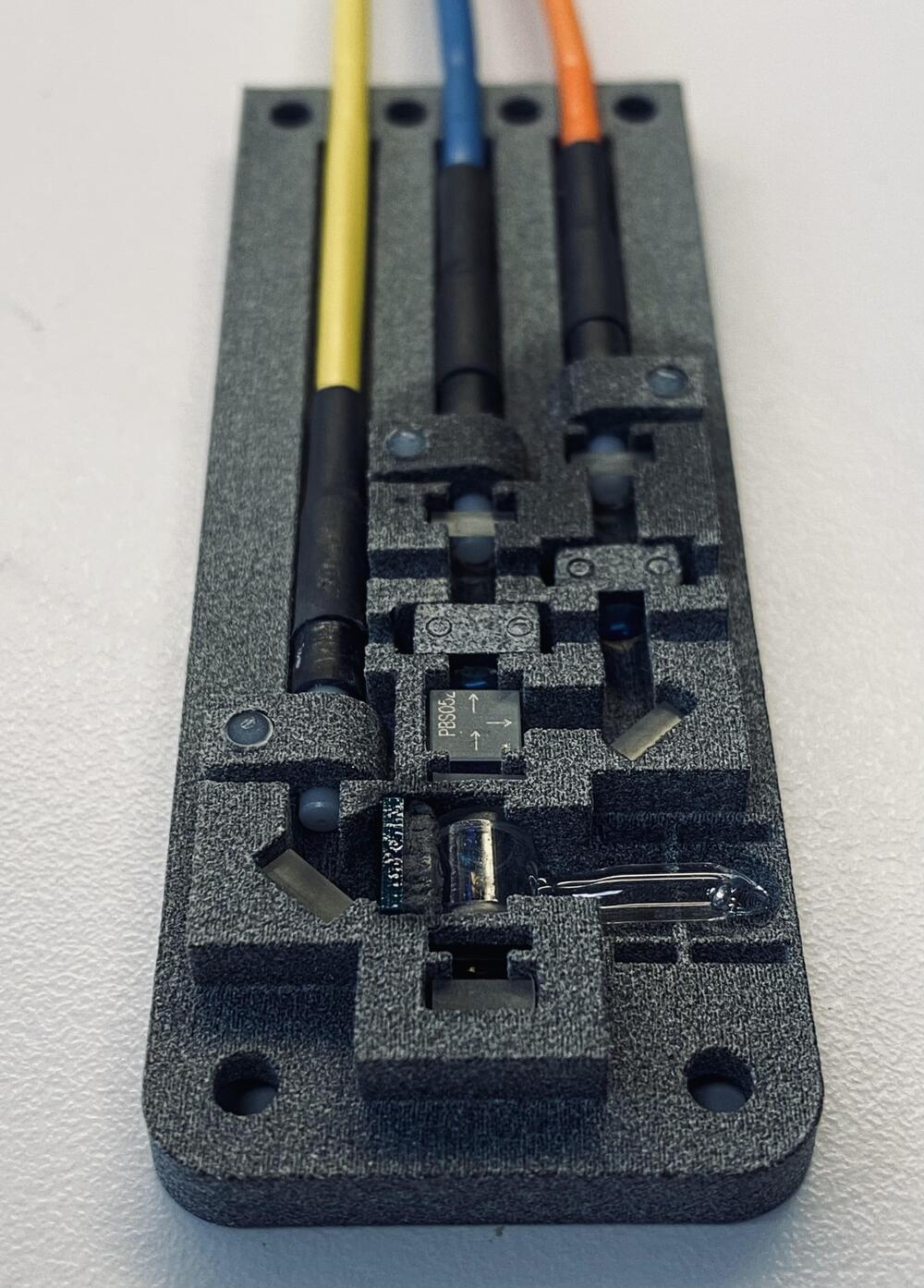

A research team at the University of Pittsburgh led by Alexander Star, a chemistry professor in the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences, has developed a fentanyl sensor that is six orders of magnitude more sensitive than any electrochemical sensor for the drug reported in the past five years. The portable sensor can also tell the difference between fentanyl and other opioids.

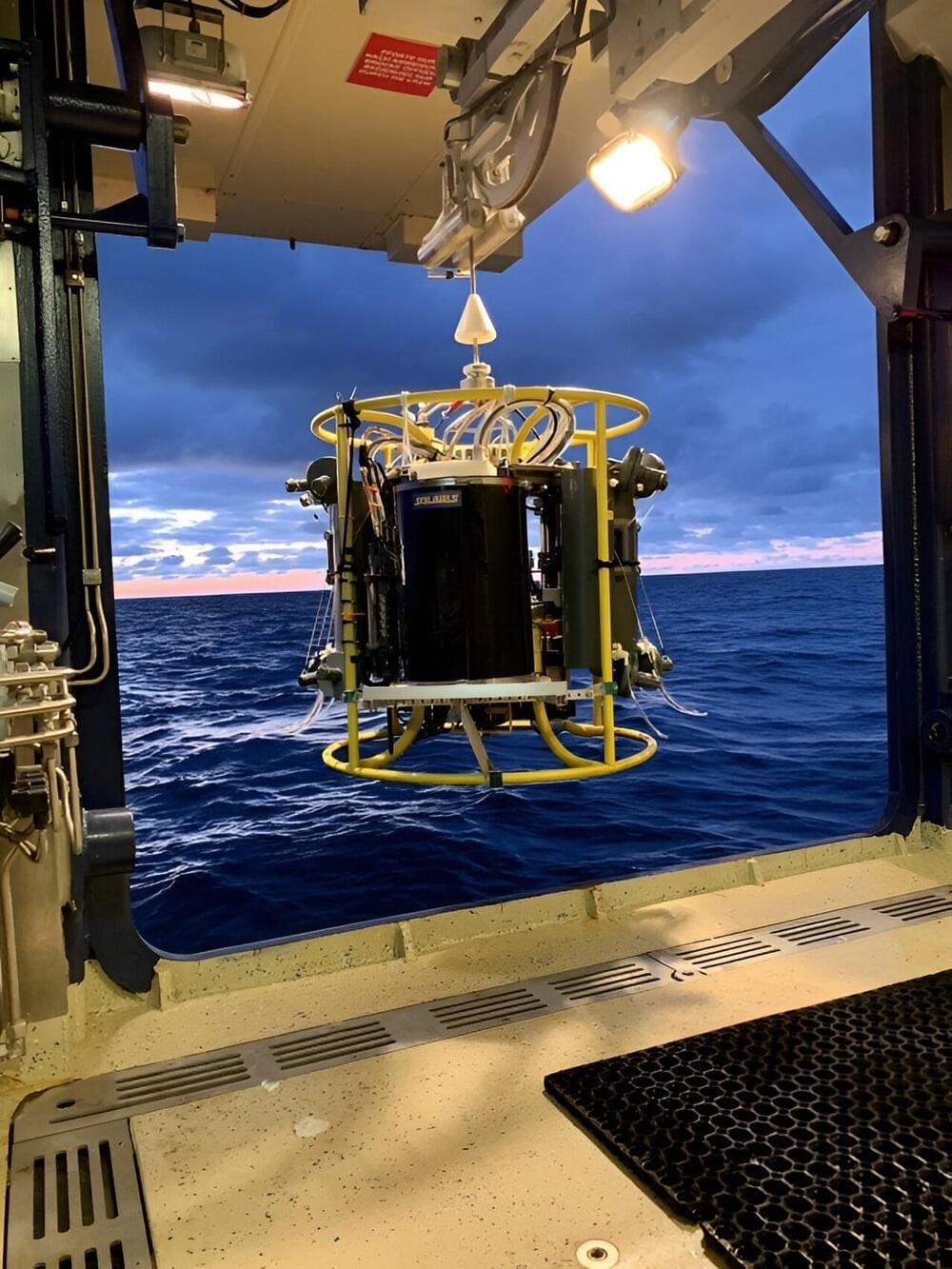

Human activities account for a substantial amount—anywhere from 20% to more than 60%—of toxic thallium that has entered the Baltic Sea over the past 80 years, according to new research by scientists affiliated with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and other institutions.

Precisely measuring the energy states of individual atoms has been a historical challenge for physicists due to atomic recoil. When an atom interacts with a photon, the atom “recoils” in the opposite direction, making it difficult to measure the position and momentum of the atom precisely. This recoil can have big implications for quantum sensing, which detects minute changes in parameters, for example, using changes in gravitational waves to determine the shape of the Earth or even detect dark matter.

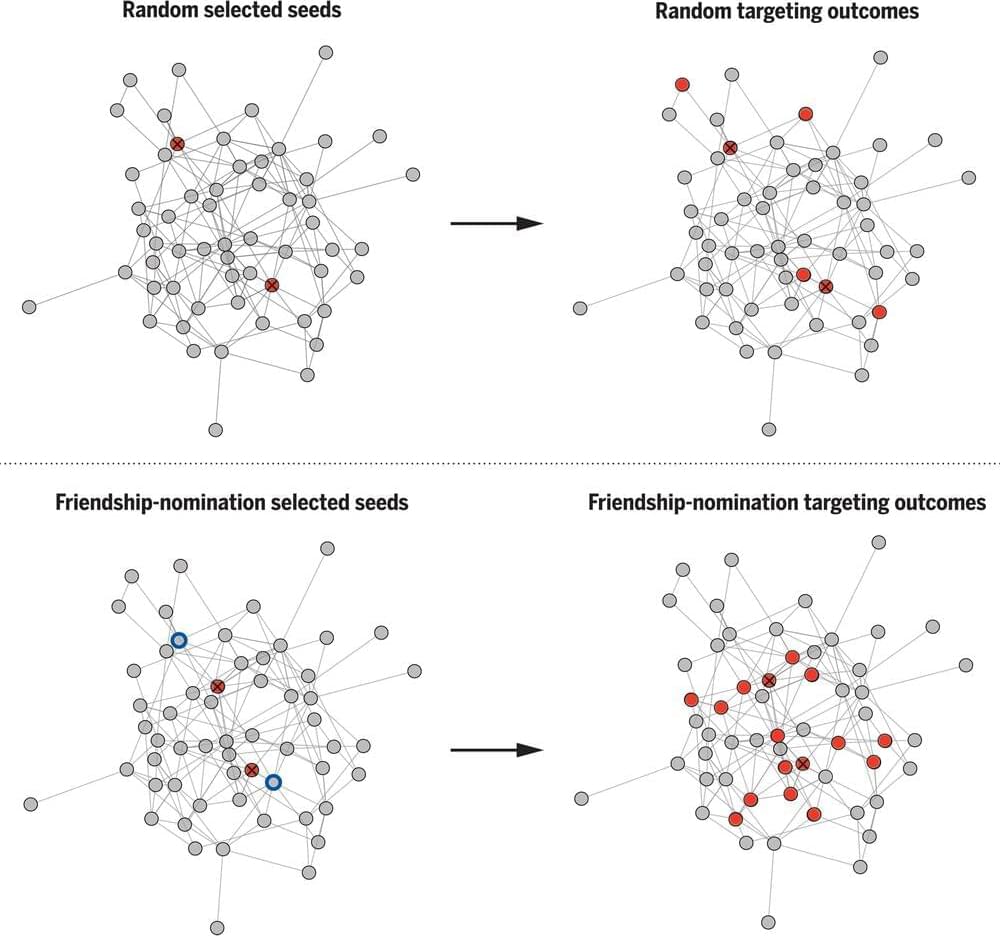

A new study co-authored by Yale sociologist Nicholas A. Christakis demonstrates that tapping into the dynamics of friendship significantly improves the possibility that a community will adopt public health and other interventions aimed at improved human well-being.

Hvidovre Hospital has the world’s first prototype of a sensor capable of detecting errors in MRI scans using laser light and gas. The new sensor, developed by a young researcher at the University of Copenhagen and Hvidovre Hospital, can thereby do what is impossible for current electrical sensors—and hopefully pave the way for MRI scans that are better, cheaper and faster.