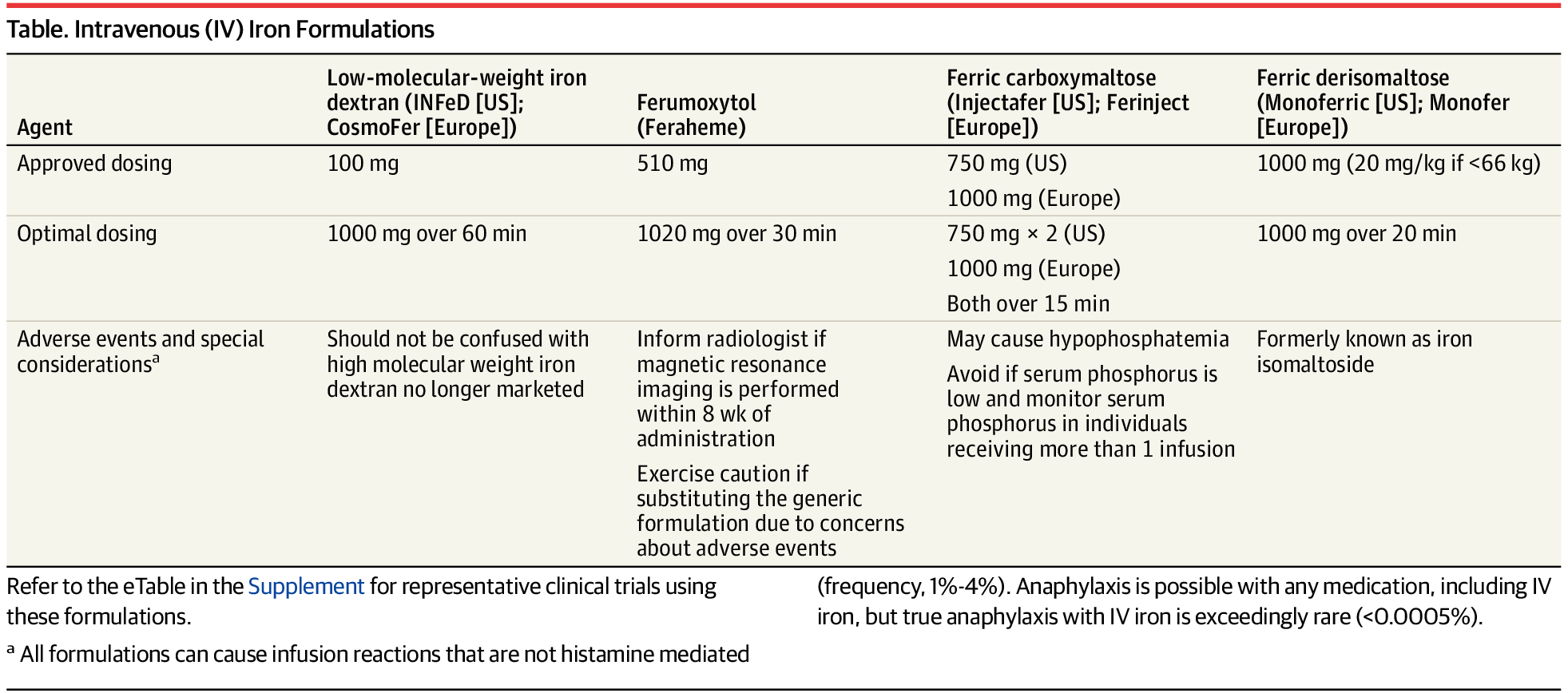

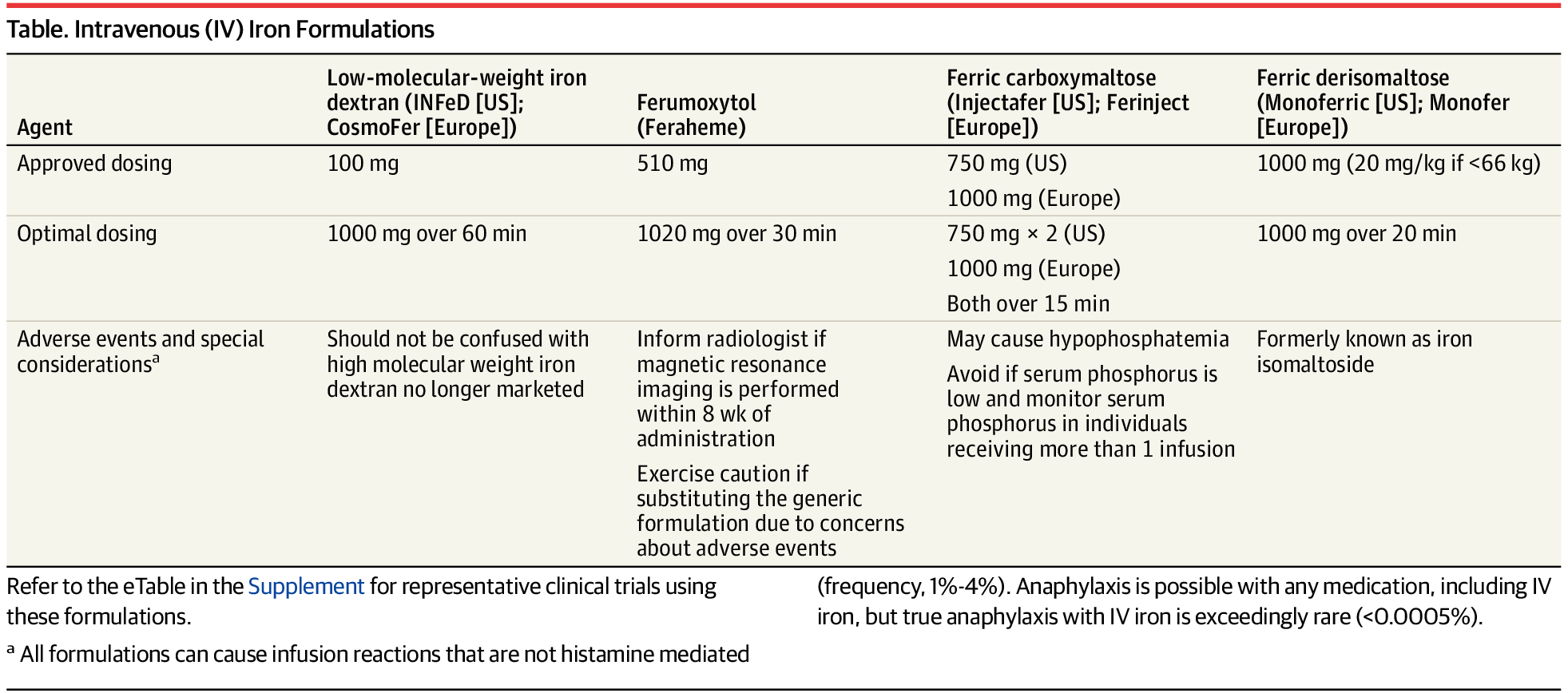

This narrative review examines the screening, diagnosis, and treatment of adults with absolute iron deficiency without anemia and iron-deficiency anemia.

Many of the robotic systems developed in the past decades are inspired by four-legged (i.e., quadruped) animals, such as dogs, cheetahs and horses. By replicating the agile movements of these animals, quadruped robots could move swiftly on the ground, crossing long distances on various terrains and rapidly completing missions.

Yet realistically and robustly replicating the fluid motions observed in animals using robotic systems can be very challenging. While some existing four-legged robots were found to be very agile and responsive to changes in their environment, these systems typically integrate advanced actuators and computational components that consume a lot of energy.

Researchers at EPFL’s CREATE Lab and Delft University of Technology (TU Delft) recently developed a new four-legged robot called PAWS (Passive Automata With Synergies), which could reproduce the fluid and adaptive movements of animals using fewer actuators. This robot, introduced in a paper in Nature Machine Intelligence, leverages so-called motor synergies, which are coordinated patterns of muscle activation that allow animals to perform agile motions consuming less energy.

Everyone needs to see “Starship Troopers.” It’s just a great movie – we’re doing our part! Whether you’ve seen it a million times or are just curious what the hype’s about, we’ve got everything you need to know about this satirical sci-fi classic.

#StarshipTroopers #SciFi #Movies.

Things You Only Notice In Starship Troopers As An Adult | 0:00

Deleted Starship Trooper Scenes That You Never Knew Existed | 9:30

The Most Pause-Worthy Moments In Starship Troopers | 15:27

The Starship Troopers scene that means more than you think | 25:38

The Biggest Differences Between Starship Troopers And The Book | 30:02

What Starship Troopers Looks Like Without Special Effects | 43:26.

Visit Official Looper Website.

https://www.looper.com

The very public sharing of Gene Hackman and Betsy Arakawa’s health details raises ethical questions over privacy.

What’s Optimal For Biomarkers? https://www.patreon.com/posts/27-blood-whats-119239968Join us on Patreon! https://www.patreon.com/MichaelLustgartenPhDDiscount…

One of the key takeaways from the experiment is that quantum mechanics does not conform to classical expectations. By creating a GHZ-type paradox in 37 dimensions, the researchers demonstrated a breakdown of local realism in ways previously unexplored.

In classical terms, the paradox suggests that an event could occur without a causative link—like a letter appearing in your mailbox without a postal worker delivering it. In quantum terms, the experiment showed that the relationship between entangled particles was so deeply nonlocal that their correlations could not be explained by any hidden variables.

The research team mathematically confirmed that their experiment achieved the strongest recorded manifestation of quantum nonlocality. By showing that the paradox holds true even under extreme conditions, they provided new evidence that classical models fail to explain the quantum world.