Quantum metals are metals where quantum effects—behaviors that normally only matter at atomic scales—become powerful enough to control the metal’s macroscopic electrical properties.

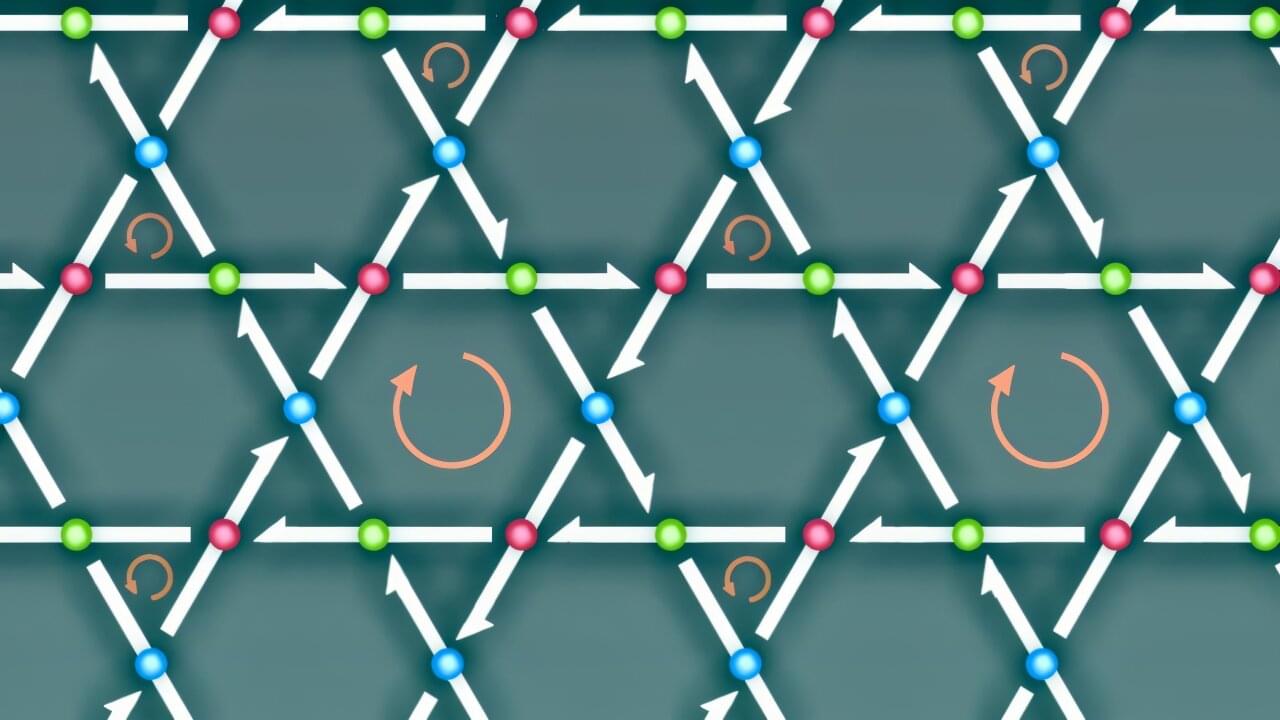

Researchers in Japan have explained how electricity behaves in a special group of quantum metals called kagome metals. The study is the first to show how weak magnetic fields reverse tiny loop electrical currents inside these metals. This switching changes the material’s macroscopic electrical properties and reverses which direction has easier electrical flow, a property known as the diode effect, where current flows more easily in one direction than the other.

Notably, the research team found that quantum geometric effects amplify this switching by about 100 times. The study, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, provides the theoretical foundation that could eventually lead to new electronic devices controlled by simple magnets.