October 23rd — 25th at AT&T Conference Center in Austin TX — Join us for 2 days to connect with visionaries, spark bold ideas, and dive into the future of space. Don’t just watch—be part of the conversation.

Ladislaus Bortkiewicz was born in Saint Petersburg, Imperial Russia, to two ethnic Polish parents: Józef Bortkiewicz and Helena Bortkiewicz (née Rokicka). His father was a Polish nobleman who served in the Russian Imperial Army.

Bortkiewicz graduated from the Law Faculty in 1890. In 1898 he published a book about the Poisson distribution, titled The Law of Small Numbers. [ 1 ] In this book he first noted that events with low frequency in a large population follow a Poisson distribution even when the probabilities of the events varied. It was that book that made the Prussian horse-kicking data famous. The data gave the number of soldiers killed by being kicked by a horse each year in each of 14 cavalry corps over a 20-year period. Bortkiewicz showed that those numbers followed a Poisson distribution. The book also examined data on child-suicides. Some [ 2 ] have suggested that the Poisson distribution should have been named the “Bortkiewicz distribution.”

In political economy, Bortkiewicz is important for his analysis of Karl Marx’s reproduction schema in the last two volumes of Capital. Bortkiewicz identified a transformation problem in Marx’s work. Making use of Dmitriev’s analysis of Ricardo, Bortkiewicz proved that the data used by Marx was sufficient to calculate the general profit rate and relative prices. Though Marx’s transformation procedure was not correct—because it did not calculate prices and profit rate simultaneously, but sequentially—Bortkiewicz has shown that it is possible to get the correct results using the Marxian framework, i.e. using the Marxian variables constant capital and variable capital it is possible to obtain the profit rate and the relative prices in a three-sector model. This “correction of the Marxian system” has been the great contribution of Bortkiewicz to classical and Marxian economics but it was completely unnoticed until Paul Sweezy’s 1942 book “Theory of Capital ist Development”

Google is investing an additional €5 billion in Belgium over the next two years to expand its cloud and AI infrastructure. This includes expansions of our data center campuses in Saint-Ghislain and will add another 300 full time jobs. We’ve also announced new agreements with Eneco, Luminus and Renner which will support the development of new onshore wind farms and support the grid with clean energy.

Our commitment goes beyond infrastructure. We’re also equipping Belgians with the skills needed to thrive in an AI-driven economy, at no cost and will fund non-profits to provide free, practical AI training for low-skilled workers.

This is an extraordinary time for European innovation and its digital and economic future. Google is deepening its roots in Belgium and investing in its residents to unlock significant economic opportunities for the country, helping to ensure it remains a leader in technology and AI.

What a difference a year makes! Today Hera’s asteroid mission for planetary defence is cruising through deep space on the far side of the Sun, headed to its final destination: the Didymos binary asteroid system. But a year ago, on 7 October 2024, it was unsure if the mission was ever going to take off at all.

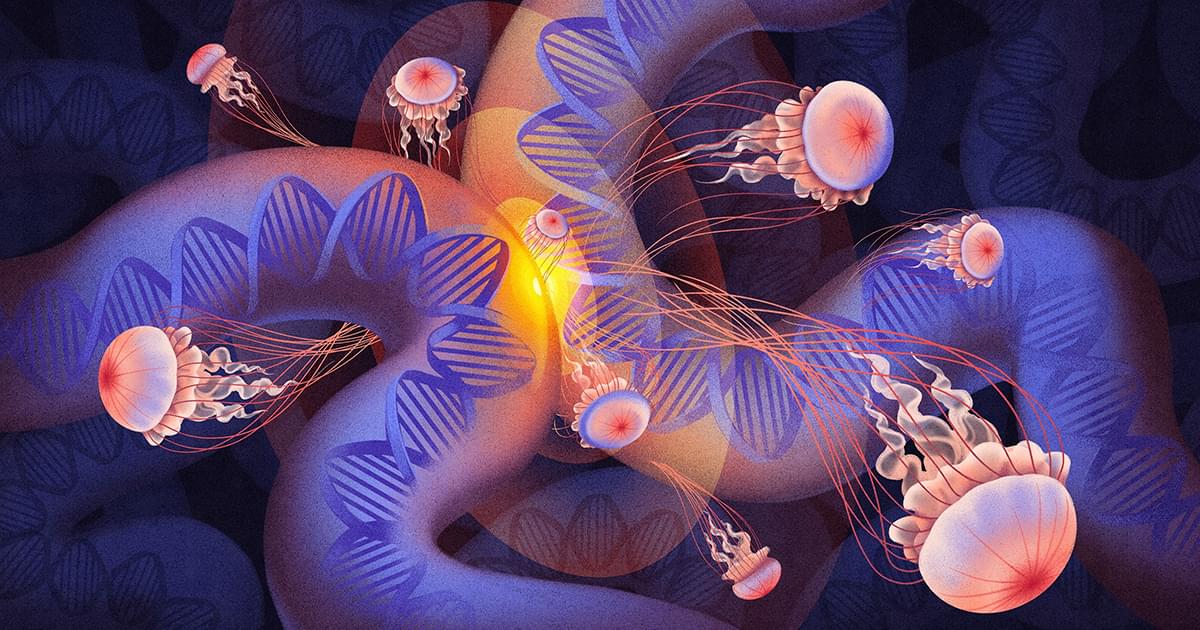

Since Madeline Lancaster first created brain organoids back in 2013, they have become widely used for brain research around the world. But what exactly are they? Are they effectively miniature brains in dishes? Could implanting them in animals create super-smart mice? How close are we to crossing ethical lines? Michael Le Page visited Lancaster at her lab at the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge, UK, to find out.

Learn more ➤ https://www.newscientist.com/article/.… ➤ https://bit.ly/NSYTSUBS Get more from New Scientist: Official website: https://bit.ly/NSYTHP Facebook: https://bit.ly/NSYTFB Twitter: https://bit.ly/NSYTTW Instagram: https://bit.ly/NSYTINSTA LinkedIn: https://bit.ly/NSYTLIN About New Scientist: New Scientist was founded in 1956 for “all those interested in scientific discovery and its social consequences”. Today our website, videos, newsletters, app, podcast and print magazine cover the world’s most important, exciting and entertaining science news as well as asking the big-picture questions about life, the universe, and what it means to be human. New Scientist https://www.newscientist.com/ 00:00 Introduction 00:54 Making the first brain organoid 01:52 What are brain organoids? 03:12 What makes our brains unique? 04:08 Modelling disease 07:01 Transplanting organoids into animals 10:41 Could we make full-sized brains? 13:19 Are brain organoids conscious? 15:21 Ethical guidelines.

Subscribe ➤ https://bit.ly/NSYTSUBS

Get more from New Scientist:

Official website: https://bit.ly/NSYTHP

Facebook: https://bit.ly/NSYTFB

Twitter: https://bit.ly/NSYTTW

Instagram: https://bit.ly/NSYTINSTA

LinkedIn: https://bit.ly/NSYTLIN

About New Scientist:

New Scientist was founded in 1956 for “all those interested in scientific discovery and its social consequences”. Today our website, videos, newsletters, app, podcast and print magazine cover the world’s most important, exciting and entertaining science news as well as asking the big-picture questions about life, the universe, and what it means to be human.

New Scientist.

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has decided to award the 2025 Nobel Prize in chemistry to Susumu Kitagawa, Richard Robson and Omar M. Yaghi \.

Painting walls in light colors, insulating roofs, choosing medium-sized windows, and aligning buildings to the sun’s path may seem like simple choices. But they could provide powerful defenses against climate change for millions of people in the world’s most vulnerable regions.

That’s the message of a study, appearing in the journal Energy and Buildings, which identifies low-cost, climate-smart design strategies as crucial for future housing in Latin America’s rapidly warming cities.

Researchers used computer simulations to test how various climate-resilient building projects would perform under current and projected climate conditions in five major cities—Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, in Brazil, Santiago (Chile), Bogotá (Colombia), and Lima (Peru).