Developers are navigating confusing gaps between expectation and reality. So are the rest of us.

For the first time, researchers at UBC have demonstrated how to reliably produce an important type of human immune cell — known as helper T cells — from stem cells in a controlled laboratory setting. The findings, published today in Cell Stem Cell, overcome a major hurdle that has limited the development, affordability and large-scale manufacturing of cell therapies. The discovery could pave the way for more accessible and effective off-the-shelf treatments for a wide range of conditions like cancer, infectious diseases, autoimmune disorders and more.

“This is a major step forward in our ability to develop scalable and affordable immune cell therapies.”

Dr. Peter Zandstra

Ranked among the world’s top medical schools with the fifth-largest MD enrollment in North America, the UBC Faculty of Medicine is a leader in both the science and the practice of medicine. Across British Columbia, more than 12,000 faculty and staff are training the next generation of doctors and health care professionals, making remarkable discoveries, and helping to create the pathways to better health for our communities at home and around the world.

DeepSeek V4 to challenge OpenAI GPT and Anthropic Claude with coding breakthroughs

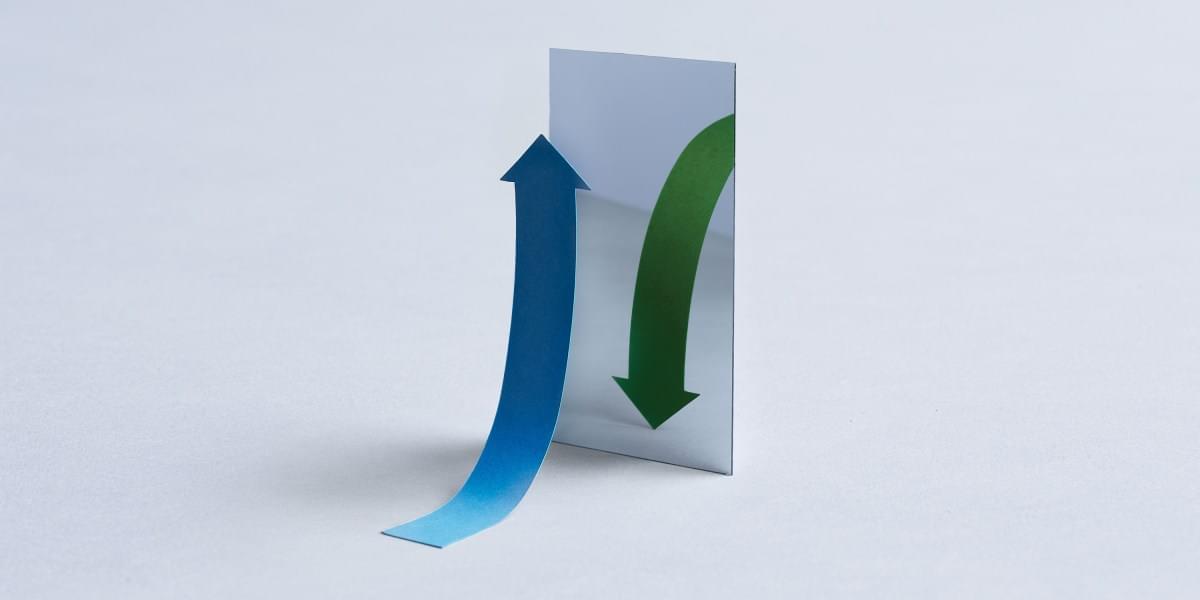

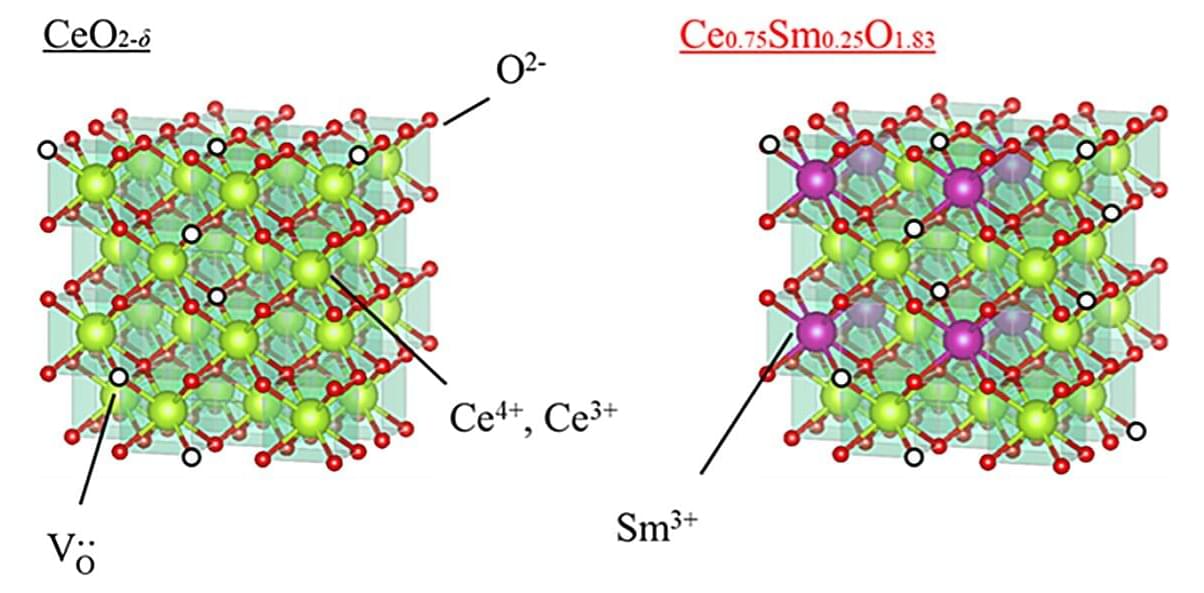

Under the threat of climate change and geopolitical tensions related to fossil fuels, the world faces an urgent need to find sustainable and renewable energy solutions. While wind, solar, and hydroelectric power are key renewable energy sources, their output strongly depends on environmental conditions, meaning they are unable to provide a stable electricity supply for modern grids.

Solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs), on the other hand, represent a promising alternative; these devices produce electricity on demand directly from clean electrochemical reactions involving hydrogen and oxygen.

However, existing SOFC designs still face technical limitations that hinder their widespread adoption for power generation. SOFCs typically rely on bulk ceramic electrolytes and require high operating temperatures, ranging from 600–1,000 °C. This excessive heat not only forces manufacturers to use expensive, high-performance materials, but also leads to earlier component degradation, limiting the cell’s service life and driving up costs.

But there is nothing in biology yet found that indicates the inevitability of death. This suggests to me that it is not at all inevitable, and that it is only a matter of time before the biologists discover what it Читать

A research team at the Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf (HZDR) has developed a radiopharmaceutical molecule marker that can visualize tumors that carry the cell surface protein Nectin-4. This primarily occurs in the body in cases of urothelial carcinoma, a common form of bladder cancer.

In pre-clinical trials, the drug candidate, NECT-224, proved stable and was successfully used in humans for the first time. As the team has now reported in the Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, in the future, it could be used to better identify patients who would benefit from Nectin-4-targeted therapies.

Many modern cancer drugs only work when the target structure to which they are supposed to bind is also present on the tumor cells. In the case of urothelial carcinoma, the cell surface protein Nectin-4 lends itself to this purpose. It serves as a “door sign” for antibody-coupled agents that are able to eliminate tumor cells in a targeted fashion. But not every tumor produces the same amount of Nectin-4.

Over the past few decades, researchers have used ultracold atomic gases to simulate high-temperature superconductors and other materials in which electrons interact strongly. Frustratingly, these experiments have failed to uncover the temperature dependence of certain “p-wave” interactions relevant to some superconductors and superfluids. Now Kenta Nagase and his colleagues at the Institute of Science Tokyo have tracked how these interactions change as a cloud of lithium atoms is cooled toward absolute zero [1]. The results could help scientists better understand the behavior of certain exotic superconductors.

In a p-wave interaction, particles collide with each other in such a way that their interaction strength depends on their relative orientations. The inherent complexity of these interactions, such as their occurrence through three different scattering channels, meant that their predicted temperature dependence lacked experimental confirmation. To surmount this hurdle, Nagase and his colleagues isolated and analyzed the contributions to the interactions from each channel. They repeated their experiment at many temperatures, controlled by the strength of the optical trap confining the lithium cloud.

As they cooled the lithium cloud, Nagase and his colleagues saw that the strength of p-wave interactions increased, in agreement with predictions. These interactions caused the lithium atoms to briefly form fragile molecules, mimicking the pairing of electrons in a superconductor. The measured number, angular distribution, and behavior of such molecules were also consistent with expectations. These properties had been explored in the lab only partially, so the new work provides stronger support for current models of ultracold atomic gases.

A textbook rule for the relationship between the structure and strength of a material breaks down for high-speed deformations, like those caused by strong impacts.

On the microscale, metallic materials are made of homogeneous crystalline regions—grains—separated by disordered boundaries. In general, materials with smaller grains are stronger because they have more grain boundaries, which impede deformation. But researchers have now demonstrated a radical departure from this rule: With rapid deformation, such as that from an explosive impact, finer grained metals are softer, not harder [1]. This new insight, the researchers hope, could be useful for engineers developing impact-resistant alloys for armor, aerospace structures, or hypersonic vehicles.

The yield strength of a material is the stress (force) at which it begins to deform permanently rather than springing back. At the atomic scale in crystalline materials, this deformation occurs when sections of the crystal slide past one another, facilitated by the motion of structural defects called dislocations. But at grain boundaries, dislocations are halted and can pile up, which translates into resistance to deformation and increased yield strength. Materials with smaller grains have more grain boundaries than those with larger grains, so smaller grains are associated with higher strength.

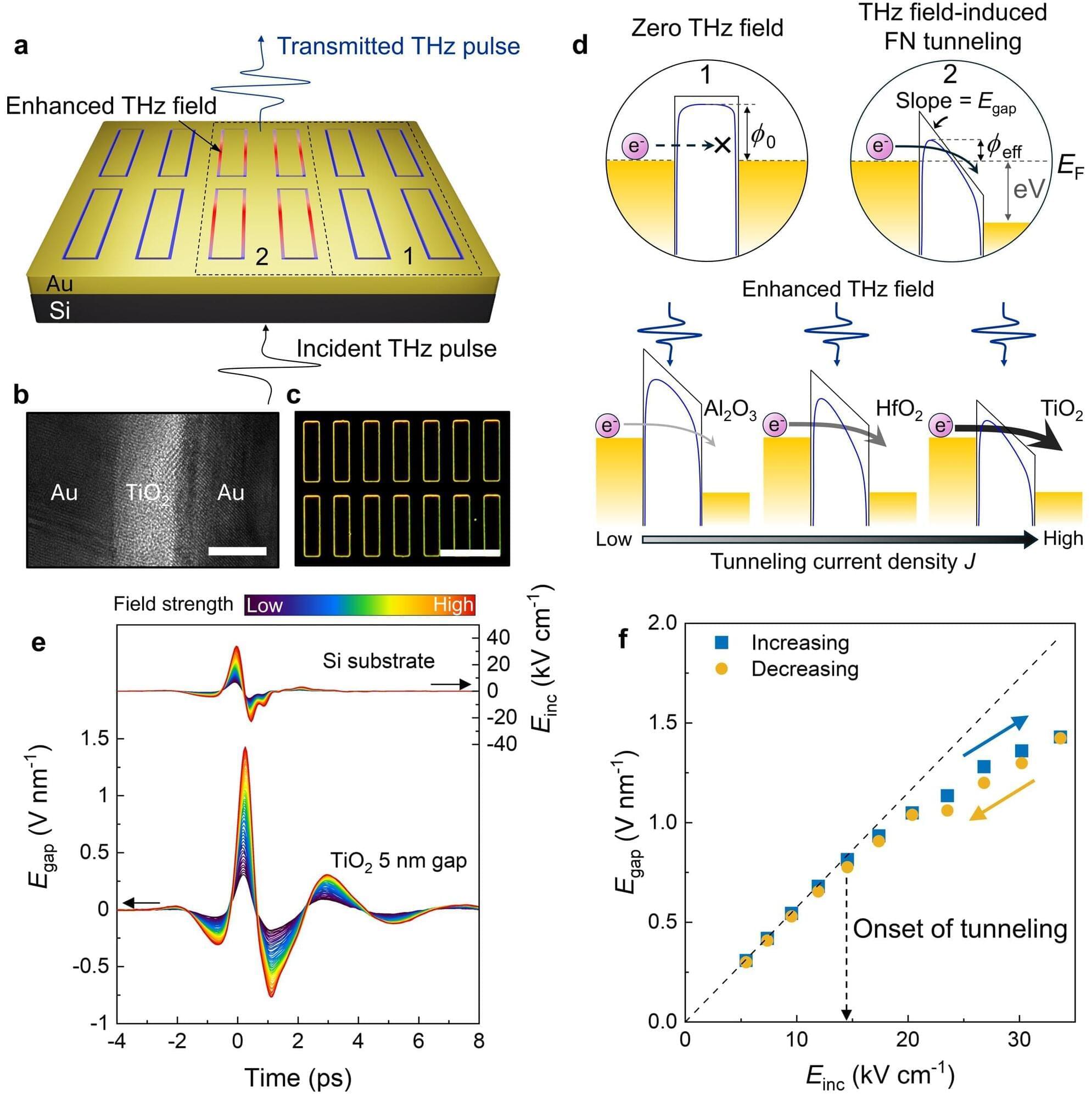

A research team affiliated with UNIST has unveiled a quantum device, capable of ultra-fast operation, a key step toward realizing technologies like 6G communications. This innovation overcomes a major hurdle that has long limited the durability of such devices under high electrical fields.

Professor Hyeong-Ryeol Park from the Department of Physics at UNIST, in collaboration with Professor Sang Woon Lee at Ajou University, has developed a terahertz quantum device that can operate reliably without suffering damage from intense electric fields—something that has been a challenge for existing technologies.