Physicists in Australia and the United Kingdom have found a way to reshape quantum uncertainty, offering a new method that bypasses the limits set by the well-known Heisenberg uncertainty principle. Their discovery could lay the groundwork for next-generation sensors with extraordinary precision, with potential uses in navigation, medical imaging, and astronomy.

The Heisenberg uncertainty principle, first introduced in 1927, states that it is impossible to know certain pairs of properties, such as a particle’s position and momentum, with unlimited accuracy at the same time. In practice, this means that increasing precision in one property inevitably reduces certainty in the other.

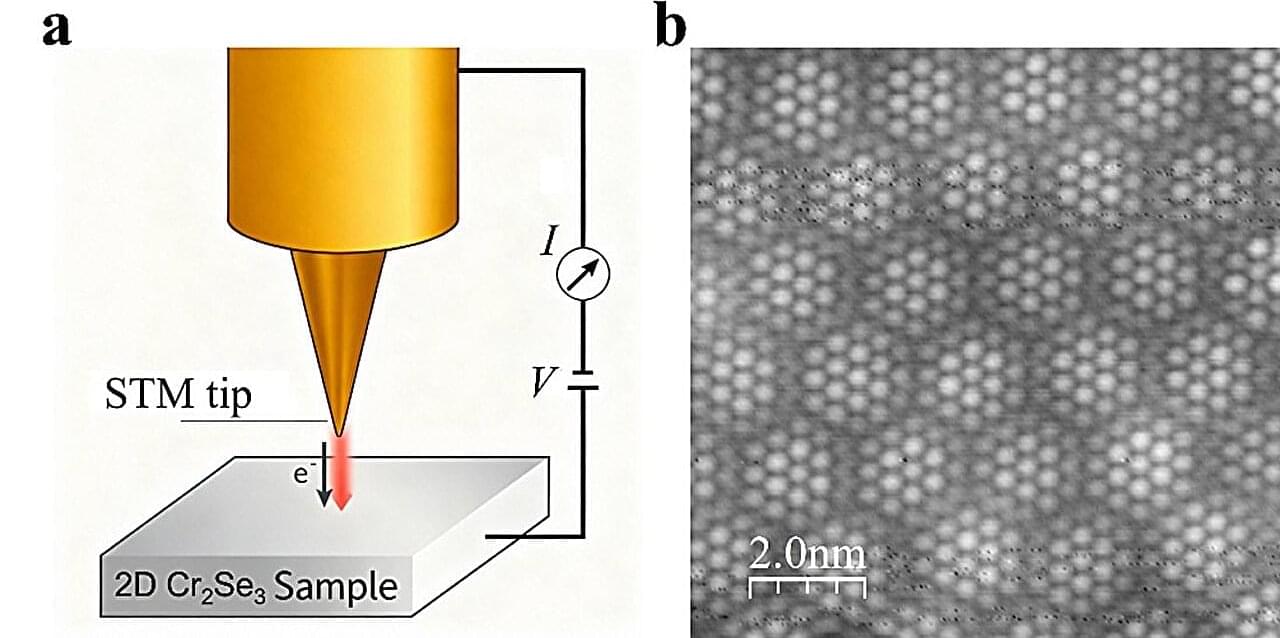

In a study published in Science Advances, researchers led by Dr. Tingrei Tan of the University of Sydney Nano Institute and School of Physics demonstrated how to design an alternative trade-off, one that allows position and momentum to be measured simultaneously with exceptional accuracy.