Getting older means losing things. Some are fine, like any f**ks you have left to give or your tolerance for cheap tequila. Others, like the ability to follow a conversation in a loud room, hit harder.

But scientists now think there’s a way to fight back. And it might start at a piano bench.

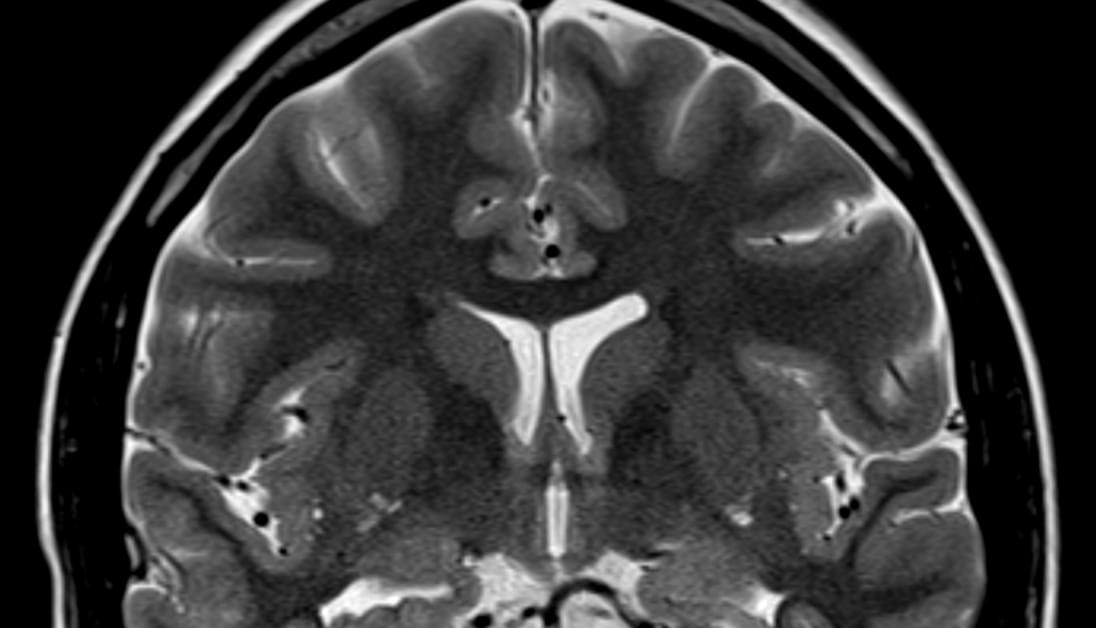

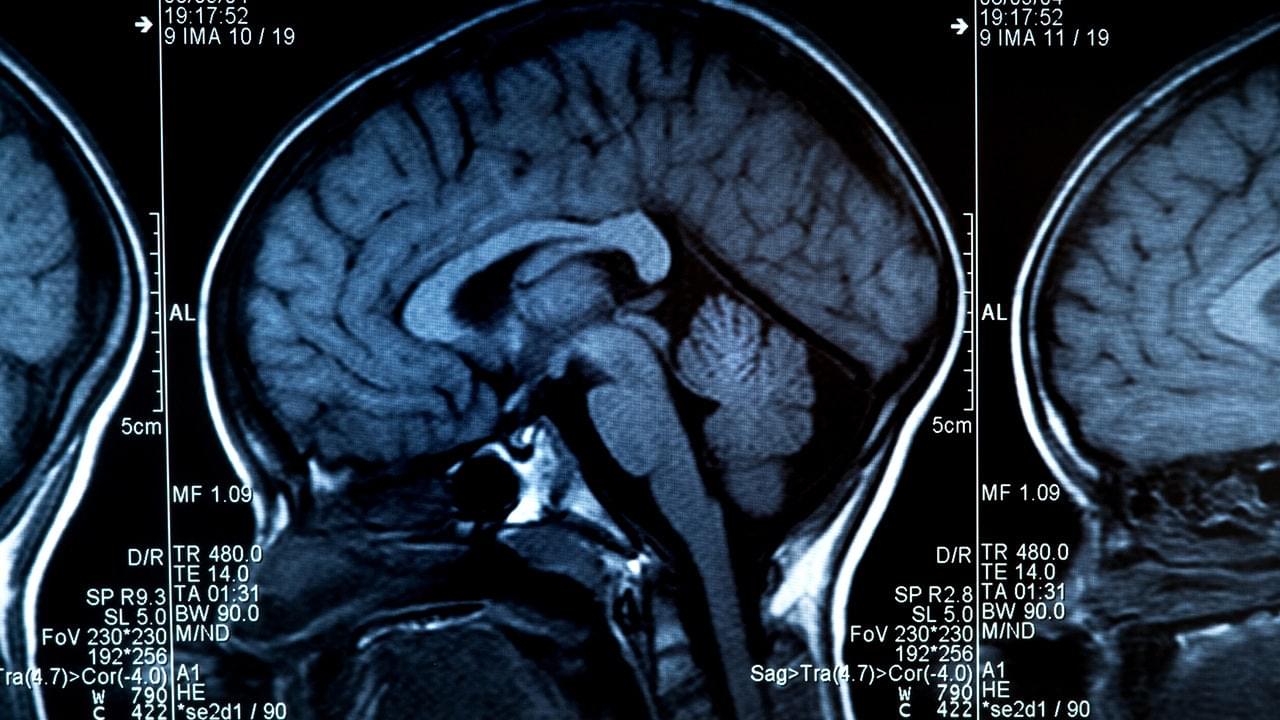

Researchers publishing in PLOS Biology found that older adults who have played music for decades have brains that function more like those of someone half their age, at least when it comes to understanding speech in loud environments. In brain scans, they showed cleaner, more focused activity while listening to spoken syllables buried in background noise. Their brains weren’t scrambling. They already knew what to do.