Researchers at Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden and at the University of Magdeburg in Germany have developed a novel type of nanomechanical resonator that combines two important features: high mechanical quality and piezoelectricity. This development could open doors to new possibilities in quantum sensing technologies.

Dell Technologies expands its computing (HPC) portfolio, offering powerful solutions to help organizations quickly innovate with confidence.

With a range of new offers, Dell delivers technologies and services to help power demanding applications while making HPC capabilities more accessible to businesses.

Dell PowerEdge servers champion advanced modeling and datasets.

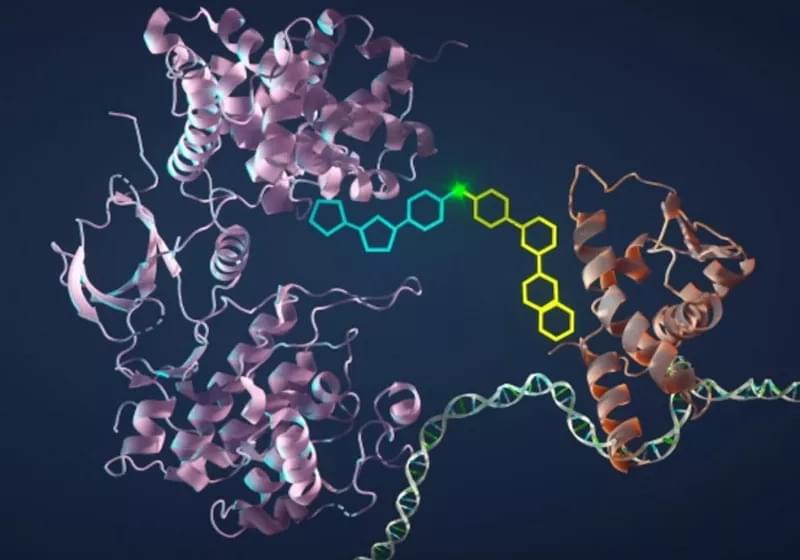

The researchers’ recently published study describes a way to re-activate apoptosis in mutated cells, which would amount to forcing cancer to self-destruct through a bioengineered, bonding molecule.

Gerald Crabtree, one of the study’s authors and a professor of development biology, said he had the idea while hiking through Kings Mountain, California, during the pandemic period. The new compound would have to bind two proteins which already exist in the cancerous cells, turning apoptosis back on and making the cancer kill itself.

“We essentially want to have the same kind of specificity that can eliminate 60 billion cells with no bystanders,” Crabtree said, so that no cell gets destroyed if it isn’t the proper target of this new killing mechanism. The two proteins in question are known as BCL6, an oncogene which suppresses apoptosis-promoting genes in the B-cell lymphoma, and CDK9, an enzyme that catalyzes gene activation instead.

In recent years, standing has been touted as a remedy to a sedentary lifestyle, especially for desk workers who spend long hours seated at their screens.

But a new study from researchers in Australia and the Netherlands has found standing for long periods of time might not be much better than sitting after all – and actually comes with its own life-threatening risks.

Just under seven years of data from 83,013 adults were collected as part of the UK Biobank, using wrist-worn devices to track their activity, sleep, and sedentary time. The amount of time individuals spent standing and sitting was matched with incidences of cardiovascular diseases – coronary heart disease, heart failure and stroke – as well as circulatory diseases – low blood pressure on standing, varicose veins, chronic venous insufficiency, and venous ulcers.

A rare species of bee was found on land where the company was planning to put a nuclear-powered artificial intelligence data center, the Financial Times reported, citing people familiar with the matter. Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg reportedly told employees during an all-hands meeting that the rare bees would further complicate a deal with an existing nuclear power plant to build the data center.

Even the exact definition of AGI is still heavily debated, making it a murky milestone.

Regardless, the stakes are high: the AI industry has poured untold billions of dollars into building out datacenters to train AI models, an investment that’s likely many years away from paying off.

Naturally, OpenAI CEO and hypeman Sam Altman has remained optimistic. During a Reddit AMA this week, he even claimed that AGI is “achievable with current hardware.”

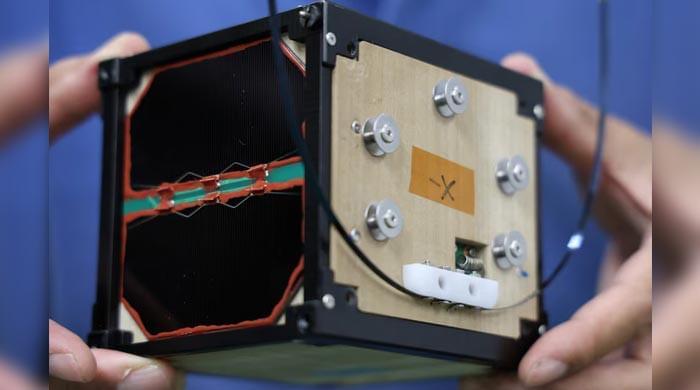

The world’s first wooden satellite, built by Japanese researchers, was launched into space on Tuesday, in an early test of using timber in lunar and Mars exploration.

LignoSat, developed by Kyoto University and homebuilder Sumitomo Forestry, will be flown to the International Space Station on a SpaceX mission, and later released into orbit about 400 kilometres above the Earth.

Named after the Latin word for “wood”, the palm-sized LignoSat is tasked to demonstrate the cosmic potential of the renewable material as humans explore living in space.

Researchers develop nanomaterial textiles for wireless power, allowing real-time data transmission without the need for bulky batteries.

Meta AI Is Ready For War

Posted in military, robotics/AI

Meta is letting the US military and defense contractors use its Llama AI model for national security purposes.

Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 146002

Posted in materials

Revealing hidden layers in superconducting nickelates.

In a collaborative effort, researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Solid State Research (MPI-FKF) have discovered a new crystal structure in La₃Ni₂O₇, a material known to exhibit high-temperature superconductivity under high pressure.