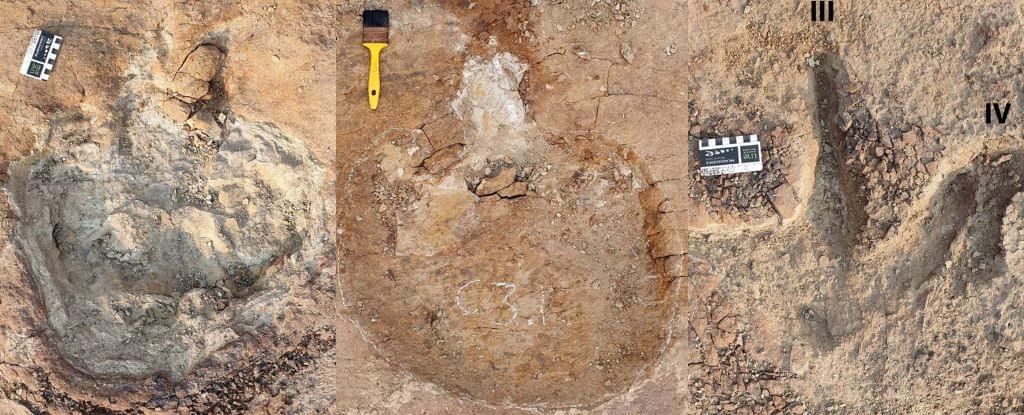

Roughly 76 million years ago, a herd of herbivorous dinosaurs left a trail of footprints that reveals different species may have walked together – and been stalked together, too.

An international team of paleontologists discovered the trackways preserved in ironstone at Canada’s Dinosaur Provincial Park. This area is known for its remarkable fossil specimens, but these are the first good set of tracks found in the area.

They reveal something fascinating: tracks from at least five ceratopsian dinosaurs appear alongside those of an ankylosaurid, meaning this could be the first evidence of multi-species herding among dinosaurs.