“Our work shows that vascular function is affected before metabolic dysfunction appears, which challenges current assumptions,” the last author of the study.

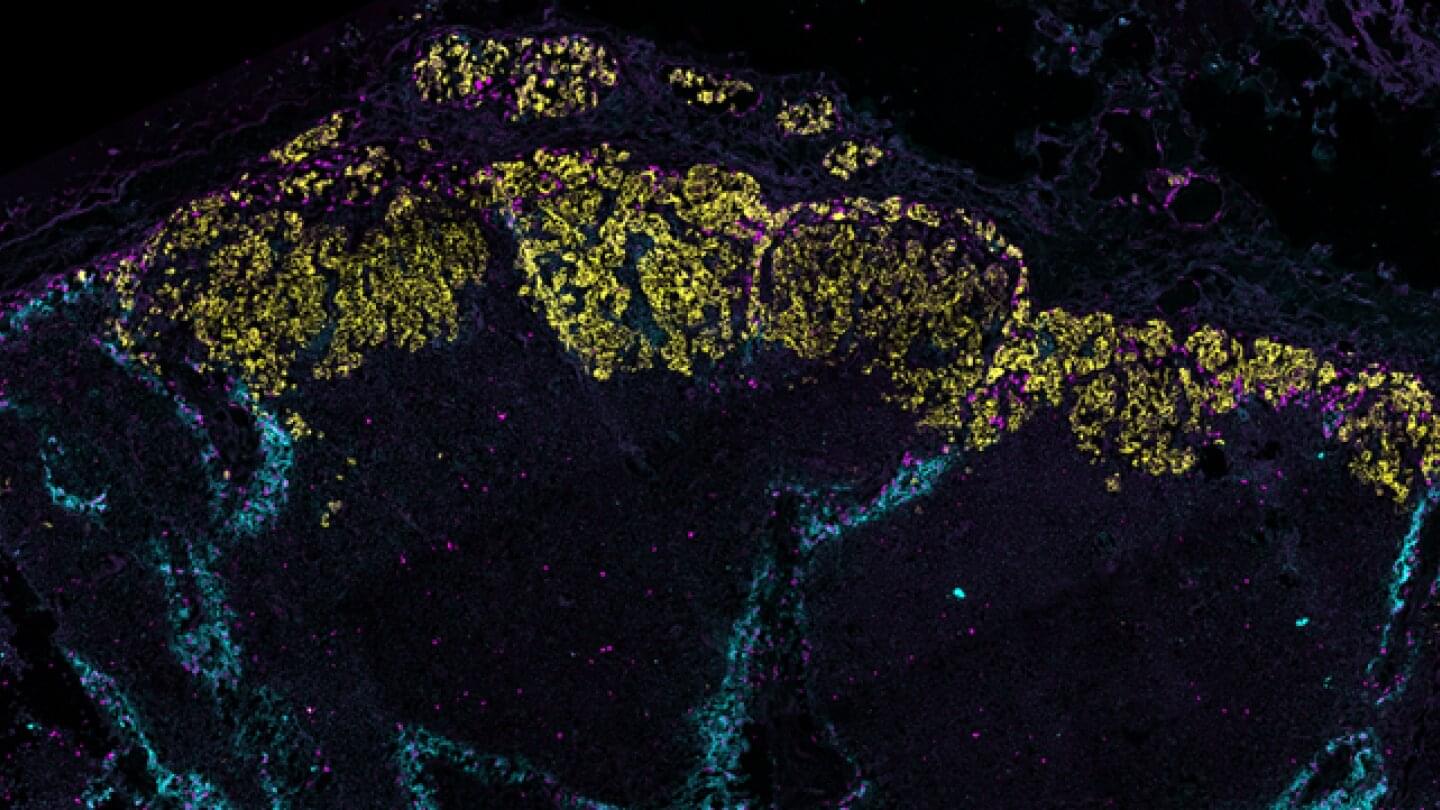

The study found that the dysfunction is driven by oxidative stress in endothelial cells, a potential early sign of future cardiovascular disease. The findings could help clinicians better assess risk and focus on preventive measures.

“We observed that early intervention can restore vascular function in affected animals, pointing to new opportunities for disease prevention later in life,” adds the first author.

A new study i reveals that sons born to mothers with type 1 diabetes may develop early vascular dysfunction – independently of metabolic health. The finding, published in Cell Reports Medicine, may help shape future strategies to prevent cardiovascular disease early in life.

Children of women with type 1 diabetes are known to be at increased risk of developing cardiovascular diseases. This new study is, according to the researchers, the first to show that the risk is linked to early dysfunction in blood vessel cells in sons, even before any metabolic issues arise.

Researchers used a combination of animal models, Swedish and Danish health registries, and a small clinical study to explore the link. Results show a sex-specific effect: only sons displayed early vascular changes.