Google signed a “definitive agreement” to acquire Wiz for $32 billion in an all-cash deal.

New research from India has made it 10 times cheaper to construct buildings on-site using a 3D printer.

A report from The Better India highlights the work of Dr. Pradeepkumar Sundarraj, who built the Kelvin6K Pro. It’s India’s first on-site construction 3D printer that can build a 2,500-square-foot home in less than 30 days.

Ultrahigh Energy Cosmic Rays are the highest-energy particles in the universe, whose energies are more than a million times what can be achieved by humans. But while the existence of UHECRs has been known for 60 years, researchers have not succeeded in formulating a satisfactory explanation for their origin that explains all the observations.

But a new theory introduced by New York University physicist Glennys Farrar provides a viable and testable explanation for how UHECRs are created.

“After six decades of effort, the origin of the mysterious highest-energy particles in the universe may finally have been identified,” says Farrar, a Collegiate Professor of Physics and Julius Silver, Rosalind S. Silver, and Enid Silver Winslow Professor at NYU. “This insight gives a new tool for understanding the most cataclysmic events of the universe: two neutron stars merging to form a black hole, which is the process responsible for the creation of many precious or exotic elements, including gold, platinum, uranium, iodine, and xenon.”

All eyes will be on Nvidia’s GPU Technology Conference this week, where the company is expected to unveil its next artificial intelligence chips. Nvidia chief executive Jensen Huang said he will share more about the upcoming Blackwell Ultra AI chip, Vera Rubin platform, and plans for following products at the annual conference, known as the GTC, during the company’s fiscal fourth quarter earnings call.

On the earnings call, Huang said Nvidia has some really exciting things to share at the GTC about enterprise and agentic AI, reasoning models, and robotics. The chipmaker introduced its highly anticipated Blackwell AI platform at last year’s GTC, which has successfully ramped up large-scale production, and made billions of dollars in sales in its first quarter, according to Huang.

Analysts at Bank of America said in a note on Wednesday that they expect Nvidia to present attractive albeit well-expected updates on Blackwell Ultra, with a focus on inferencing for reasoning models, which major firms such as OpenAI and Google are racing to develop.

The analysts also anticipate the chipmaker to share more information on its next-generation networking technology, and long-term opportunities in autonomous cars, physical AI such as robotics, and quantum computing.

In January, Nvidia announced that it would host its first Quantum Day at the GTC, and have executives from D-Wave and Rigetti discuss where quantum computing is headed. The company added that it will unveil quantum computing advances shortening the timeline to useful applications.

The same month, quantum computing stocks tanked after Huang expressed doubts over the technology’s near-term potential during the chipmaker’s financial analyst day at the Consumer Electronics Show, saying useful quantum computers are likely decades away.

Large Language Models (LLMs) both threaten the uniqueness of human social intelligence and promise opportunities to better understand it. In this talk, I evaluate the extent to which distributional information learned by LLMs allows them to approximate human behavior on tasks that appear to require social intelligence. In the first half, I will compare human and LLM responses in experiments designed to measure theory of mind—the ability to represent and reason about the mental states of other agents. Second, I present the results of an evaluation of LLMs using the Turing test, which measures a machine’s ability to imitate humans in a multi-turn social interaction.

Cameron Jones recently graduated with a PhD in Cognitive Science from the Language and Cognition Lab at UC San Diego. His work focuses on comparing humans and Large Language Models (LLMs) to learn more about how each of those systems works. He is interested in the extent to which LLMs can explain human behavior that appears to rely on world knowledge, reasoning, and social intelligence. In particular, he is interested in whether LLMs can approximate human social behavior, for instance in the Turing test, or by persuading or deceiving human interlocutors.

https://scholar.google.com/citations?… / camrobjones.

/ camrobjones.

Convergent engagement of neural and computational sciences and technologies are reciprocally enabling rapid developments in current and near-future military and intelligence operations. In this podcast, Prof. James Giordano of Georgetown University will provide an overview of how these scientific and technological fields can be — and are being — leveraged for non-kinetic and kinetic what has become known as cognitive warfare; and will describe key issues in this rapidly evolving operational domain.

James Giordano PhD, is the Pellegrino Center Professor in the Departments of Neurology and Biochemistry; Chief of the Neuroethics Studies Program; Co-director of the Project in Brain Sciences and Global Health Law and Policy; and Chair of the Subprogram in Military Medical Ethics at Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington DC. Professor Giordano is Senior Bioethicist of the Defense Medical Ethics Center, and Adjunct Professor of Psychiatry at the Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences; Distinguished Stockdale Fellow in Science, Technology, and Ethics at the United States Naval Academy; Senior Science Advisory Fellow of the SMA Branch, Joint Staff, Pentagon; Non-resident Fellow of the Simon Center for the Military Ethic at the US Military Academy, West Point; Distinguished Visiting Professor of Biomedical Sciences, Health Promotions, and Ethics at the Coburg University of Applied Sciences, Coburg, GER; Chair Emeritus of the Neuroethics Project of the IEEE Brain Initiative; and serves as Director of the Institute for Biodefense Research, a federally funded Washington DC think tank dedicated to addressing emerging issues at the intersection of science, technology and national defense. He previously served as Donovan Group Senior Fellow, US Special Operations Command; member of the Neuroethics, Legal, and Social Issues Advisory Panel of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA); and Task Leader of the Working Group on Dual-Use of the EU-Human Brain Project. Prof. Giordano is the author of over 350 peer-reviewed publications, 9 books and 50governmental reports on science, technology, and biosecurity, and is an elected member of the European Academy of Science and Arts, a Fellow of the Royal Society of Medicine (UK), and a Fulbright Professorial Fellow. A former US Naval officer, he was winged as an aerospace physiologist, and served with the US Navy and Marine Corps.

Originally released December 2023._ In today’s episode, host Luisa Rodriguez speaks to Nita Farahany — professor of law and philosophy at Duke Law School — about applications of cutting-edge neurotechnology.

They cover:

• How close we are to actual mind reading.

• How hacking neural interfaces could cure depression.

• How companies might use neural data in the workplace — like tracking how productive you are, or using your emotional states against you in negotiations.

• How close we are to being able to unlock our phones by singing a song in our heads.

• How neurodata has been used for interrogations, and even criminal prosecutions.

• The possibility of linking brains to the point where you could experience exactly the same thing as another person.

• Military applications of this tech, including the possibility of one soldier controlling swarms of drones with their mind.

• And plenty more.

In this episode:

• Luisa’s intro [00:00:00]

• Applications of new neurotechnology and security and surveillance [00:04:25]

• Controlling swarms of drones [00:12:34]

• Brain-to-brain communication [00:20:18]

• Identifying targets subconsciously [00:33:08]

• Neuroweapons [00:37:11]

• Neurodata and mental privacy [00:44:53]

• Neurodata in criminal cases [00:58:30]

• Effects in the workplace [01:05:45]

• Rapid advances [01:18:03]

• Regulation and cognitive rights [01:24:04]

• Brain-computer interfaces and cognitive enhancement [01:26:24]

• The risks of getting really deep into someone’s brain [01:41:52]

• Best-case and worst-case scenarios [01:49:00]

• Current work in this space [01:51:03]

• Watching kids grow up [01:57:03]

The 80,000 Hours Podcast features unusually in-depth conversations about the world’s most pressing problems and what you can do to solve them.

Learn more, read the summary and find the full transcript on the 80,000 Hours website:

Nita Farahany on the neurotechnology already being used to convict criminals and manipulate workers

Check out my quantum mechanics course on Brilliant! First 30 days are free and 20% off the annual premium subscription when you use our link ➜ https://brilliant.org/sabine.

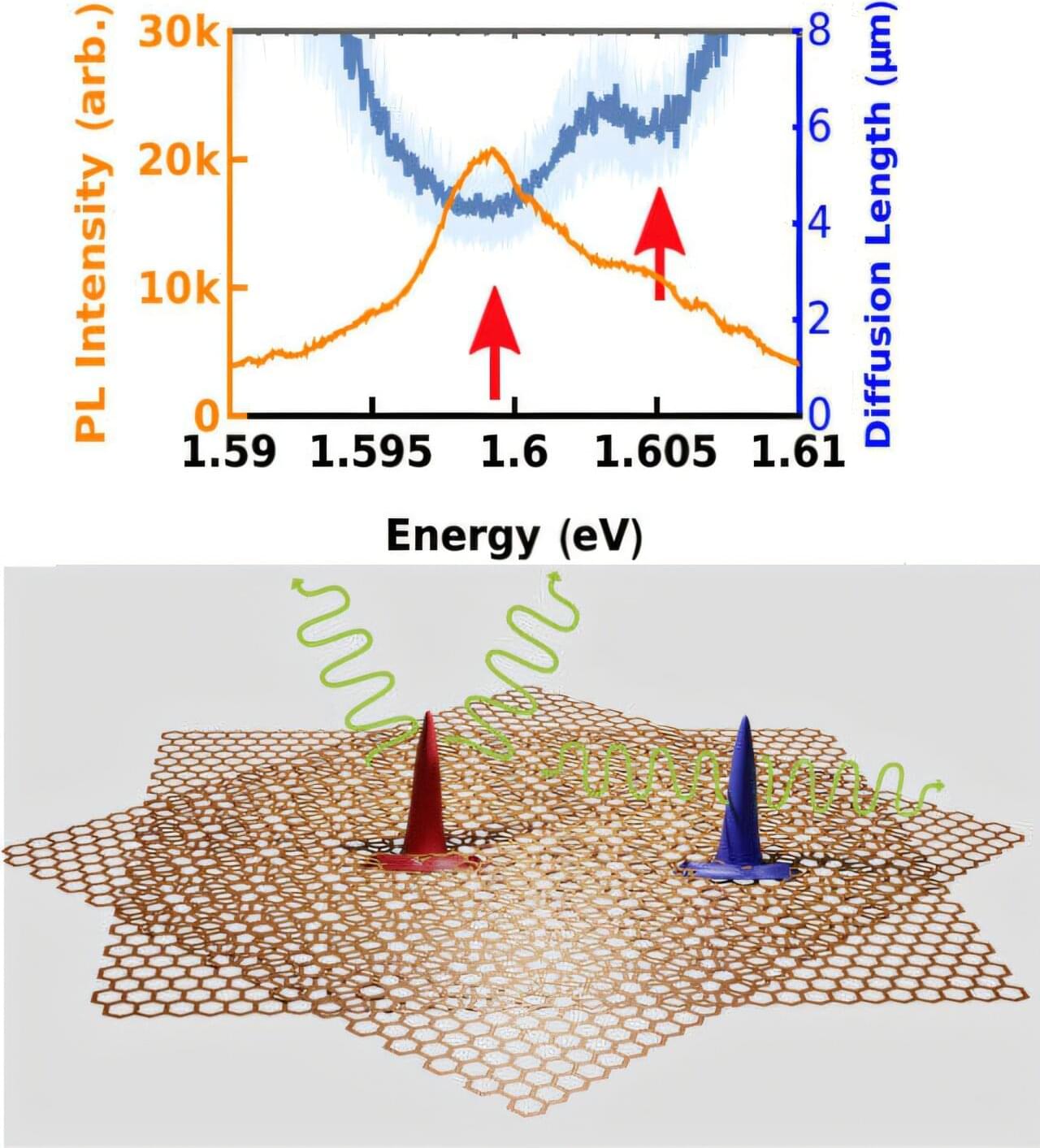

In 2020, a group of MIT researchers detected an anomaly in the nuclei of ytterbium atoms. They said that the nuclei’s strange behavior might be indicative of a “dark force” caused by a currently-undiscovered mystery particle that might make up dark matter. In 2020, the anomaly only had a significance of 3 sigma. But now, another group has confirmed it at a whopping 23 sigma! What does that mean for physics? Let’s find out.

Paper: https://journals.aps.org/prl/abstract… Check out my new quiz app ➜ http://quizwithit.com/ 💌 Support me on Donorbox ➜ https://donorbox.org/swtg 📝 Transcripts and written news on Substack ➜ https://sciencewtg.substack.com/ 👉 Transcript with links to references on Patreon ➜ / sabine 📩 Free weekly science newsletter ➜ https://sabinehossenfelder.com/newsle… 👂 Audio only podcast ➜ https://open.spotify.com/show/0MkNfXl… 🔗 Join this channel to get access to perks ➜

/ @sabinehossenfelder 🖼️ On instagram ➜

/ sciencewtg #science #sciencenews #physics #darkmatter.

🤓 Check out my new quiz app ➜ http://quizwithit.com/

💌 Support me on Donorbox ➜ https://donorbox.org/swtg.

📝 Transcripts and written news on Substack ➜ https://sciencewtg.substack.com/

👉 Transcript with links to references on Patreon ➜ / sabine.

📩 Free weekly science newsletter ➜ https://sabinehossenfelder.com/newsle…

👂 Audio only podcast ➜ https://open.spotify.com/show/0MkNfXl…

🔗 Join this channel to get access to perks ➜

/ @sabinehossenfelder.

🖼️ On instagram ➜ / sciencewtg.

#science #sciencenews #physics #darkmatter

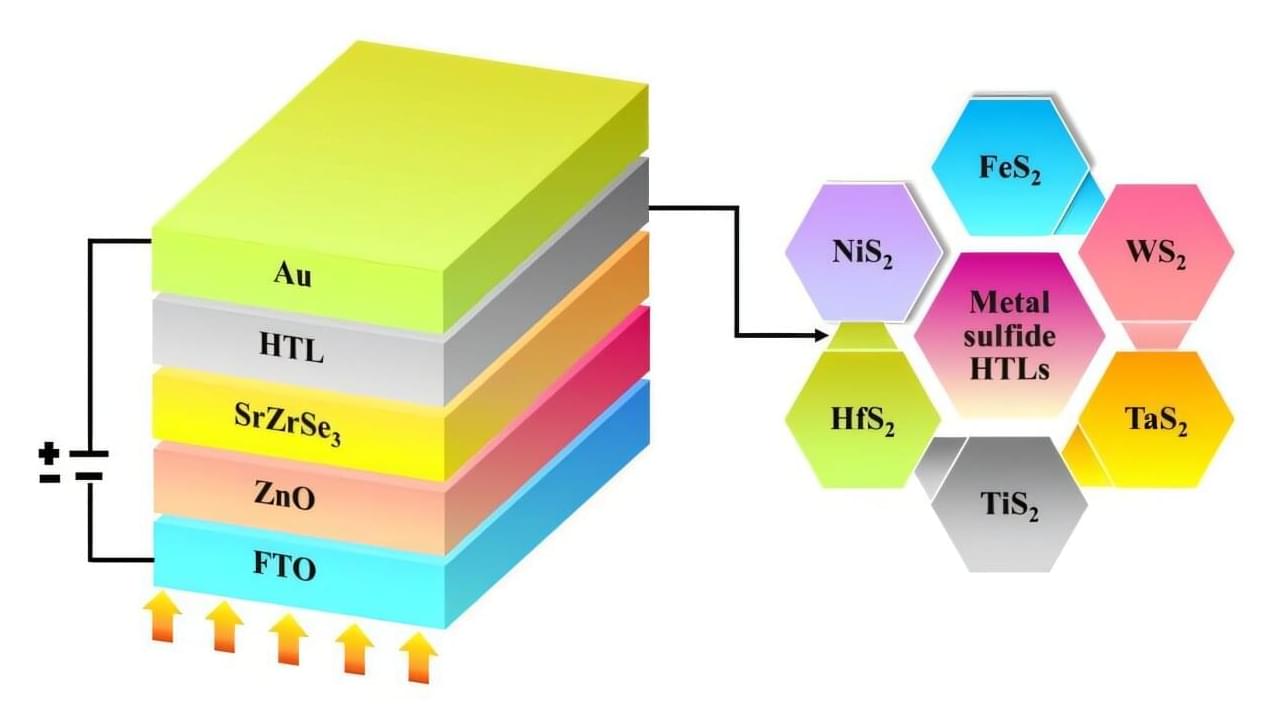

As the world increasingly prioritizes sustainable energy solutions, solar power stands out as a leading candidate for clean energy generation. However, traditional solar cells have encountered several challenges, particularly regarding efficiency and stability. But what if there was a better alternative? Imagine a solar cell that is affordable, more stable and highly efficient. Does it sound like science fiction? Not anymore. Meet SrZrSe3 chalcogenide perovskite, a rising star in the world of photovoltaics.

Our research team at the Autonomous University of Querétaro in Mexico has recently unveiled a solar cell crafted from a unique material called SrZrSe3. This novel approach is turning heads in the pursuit of affordable and efficient solar energy.

For the first time, we have successfully integrated advanced inorganic metal sulfide layers, known as hole transport layers (HTLs), with SrZrSe3 using SCAPS-1D simulations. Our work, published in Energy Technology, has significantly raised the power conversion efficiency (PCE) to an impressive rate of more than 27%, marking an advancement in solar technology.