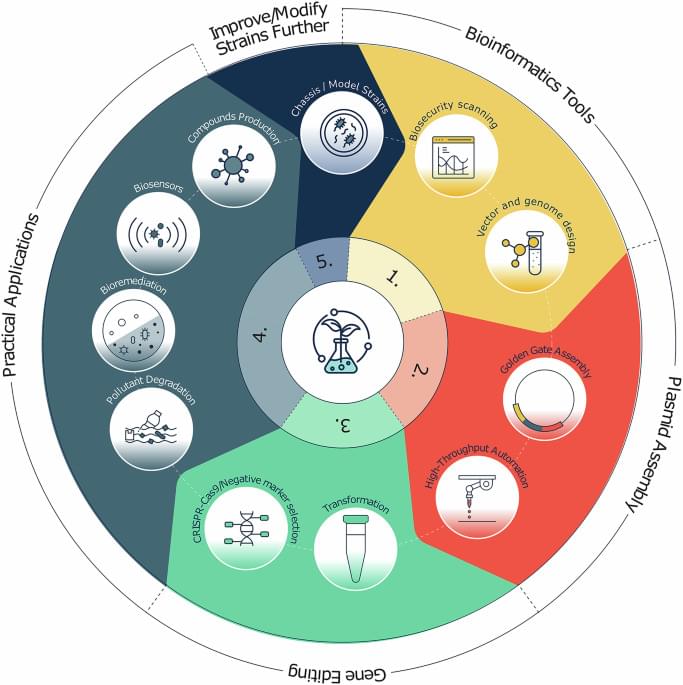

Engineering biology applies synthetic biology to address global environmental challenges like bioremediation, biosequestration, pollutant monitoring, and resource recovery. This perspective outlines innovations in engineering biology, its integration with other technologies (e.g., nanotechnology, IoT, AI), and commercial ventures leveraging these advancements. We also discuss commercialisation and scaling challenges, biosafety and biosecurity considerations including biocontainment strategies, social and political dimensions, and governance issues that must be addressed for successful real-world implementation. Finally, we highlight future perspectives and propose strategies to overcome existing hurdles, aiming to accelerate the adoption of engineering biology for environmental solutions.

The scale of global environmental challenges requires a multi-pronged approach, which utilises all the technologies at our disposal. Here, authors provide their perspective on the potential of engineering biology for environmental biotechnology, summarizing their thoughts on the key challenges and future possibilities for the field.