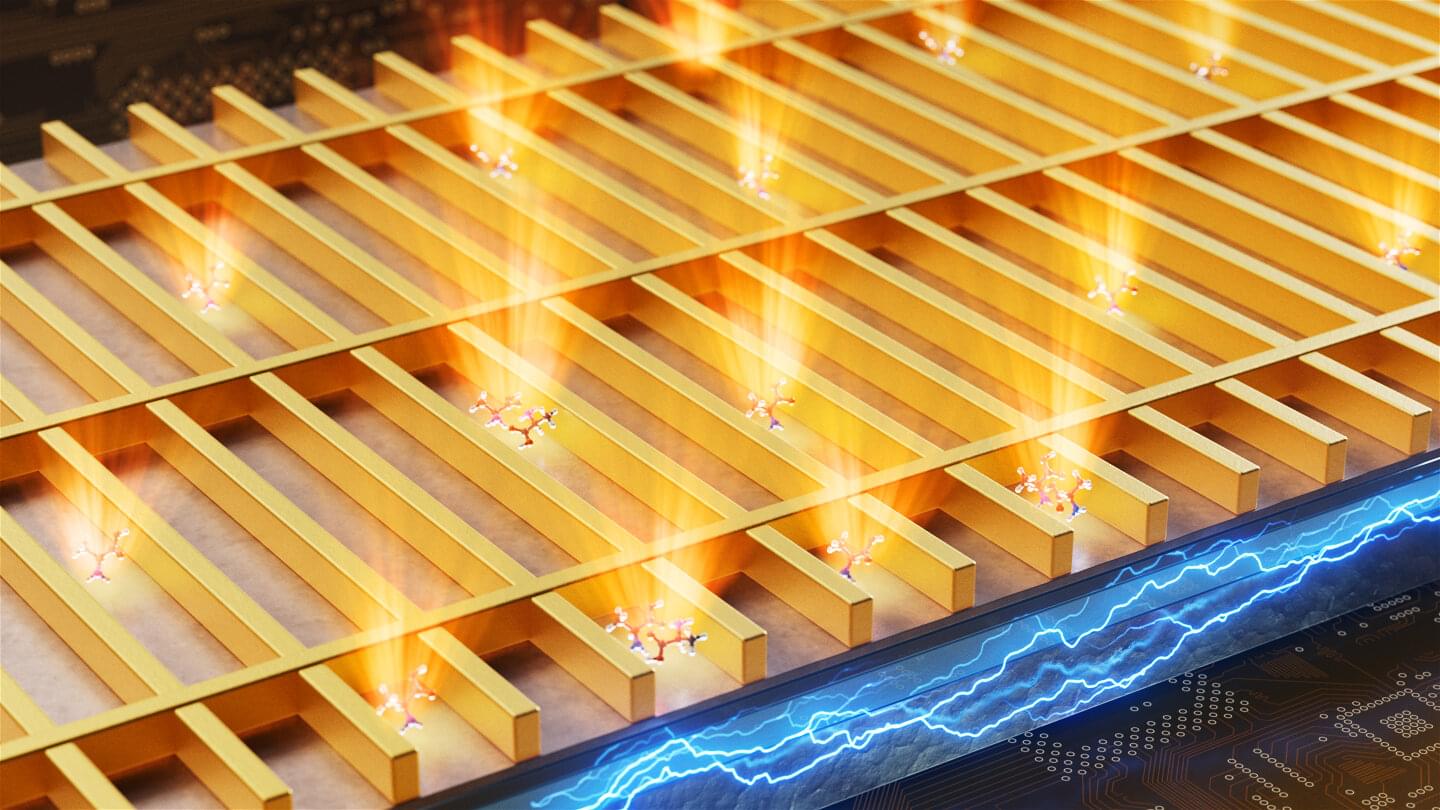

Optical biosensors use light waves as a probe to detect molecules, and are essential for precise medical diagnostics, personalized medicine, and environmental monitoring.

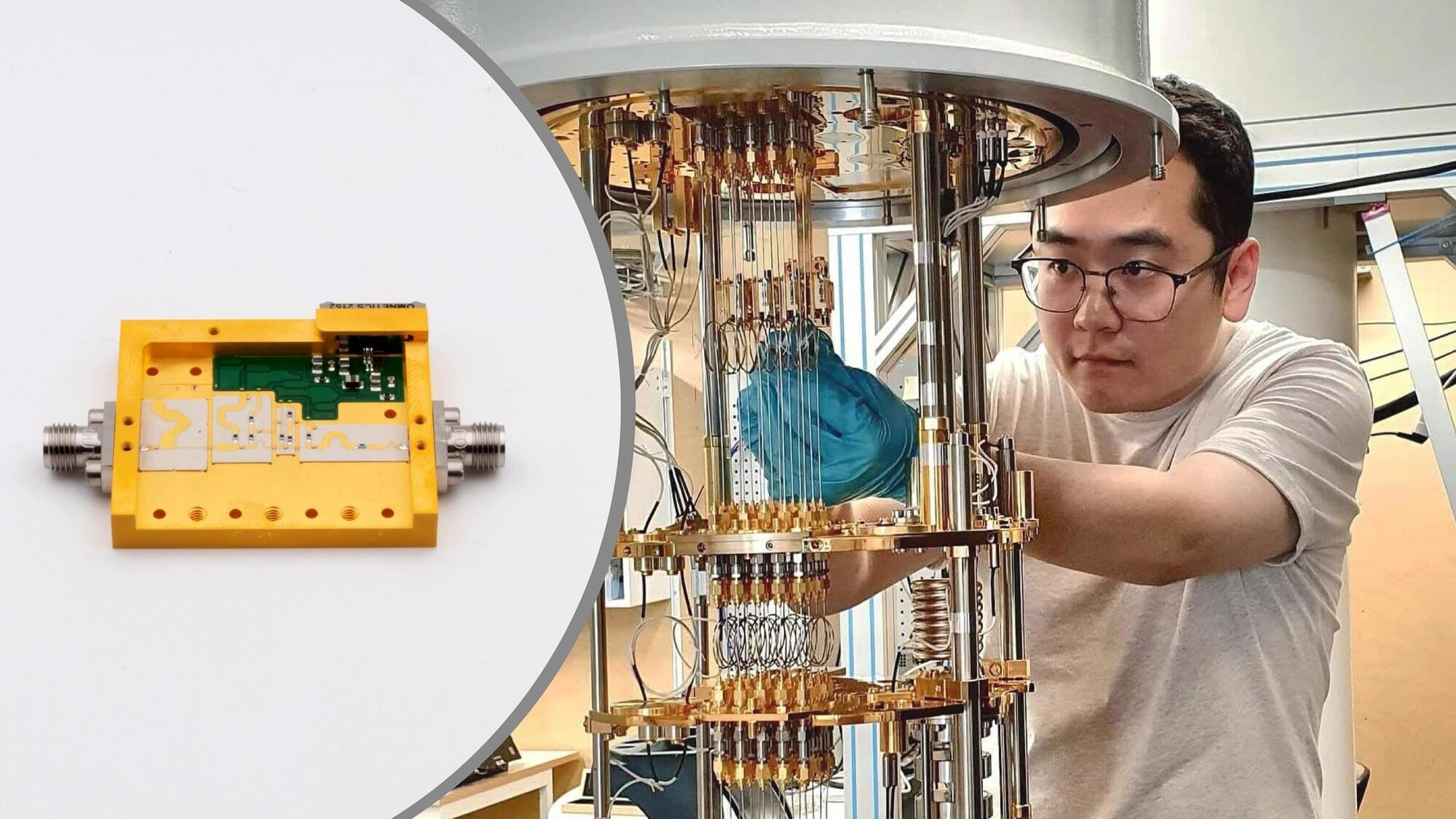

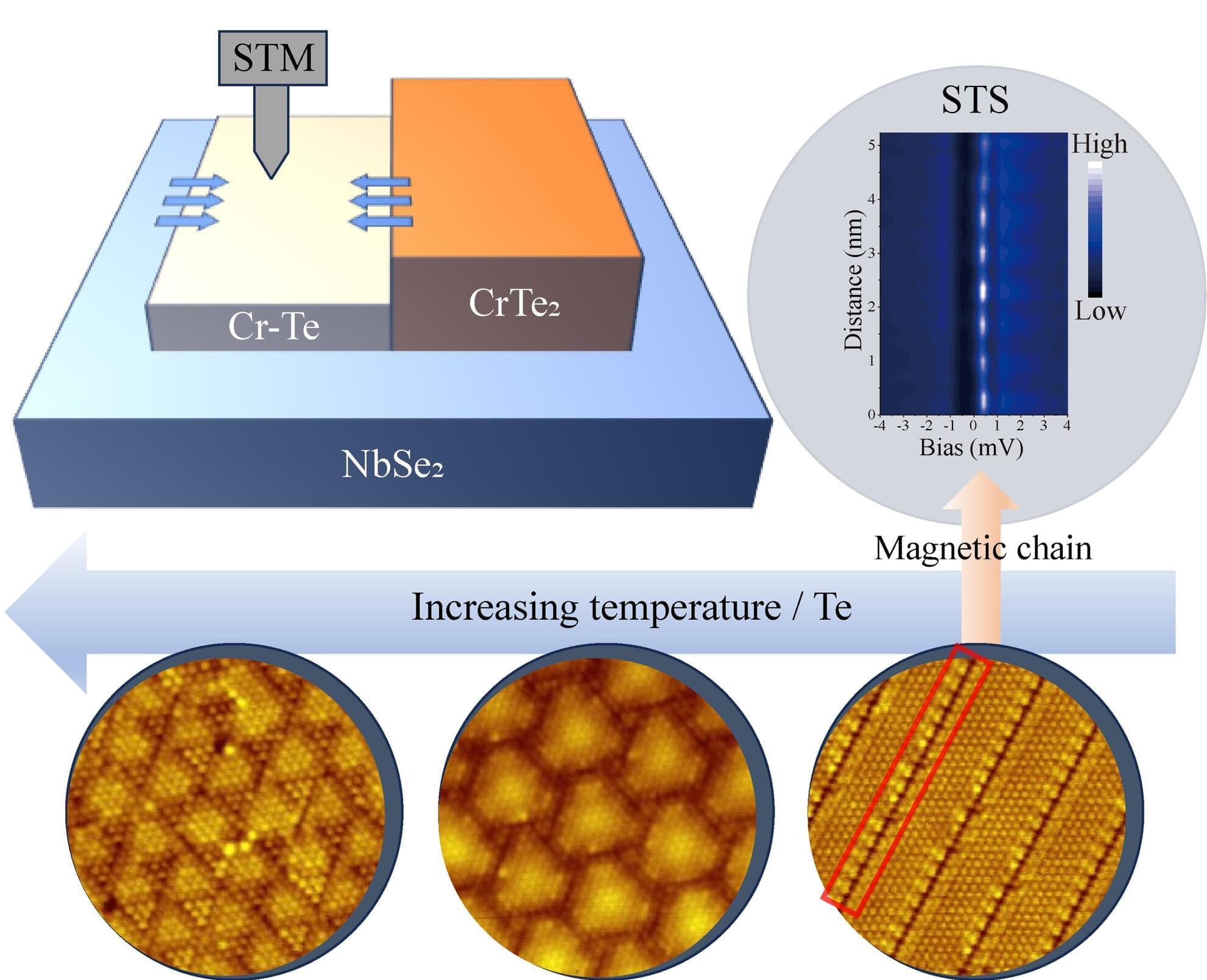

Magnetic-superconducting hybrid systems are key to unlocking topological superconductivity, a state that could host Majorana modes with potential applications in fault-tolerant quantum computing. However, creating stable, controllable interfaces between magnetic and superconducting materials remains a challenge.

Traditional systems often struggle with lattice mismatches, complex interfacial interactions, and disorder, which can obscure the signatures of topological states or mimic them with trivial phenomena. Achieving precise control over magnetic structures at the atomic scale has been a long-standing challenge in this field.

Published in Materials Futures, the researchers developed a novel sub-monolayer CrTe2/NbSe2 heterostructure. By carefully depositing Cr and Te on NbSe2 substrate, they observed a two-stage growth process: an initial compressed Cr-Te layer forms with a lattice constant of 0.35 nm, followed by the formation of an atomically flat CrTe2 monolayer with a lattice constant of 0.39 nm. Annealing the Cr-Te layer can trigger stress-relief reconstruction, which creates stripe-like patterns with edges that host localized magnetic moments, effectively forming one-dimensional magnetic chains.

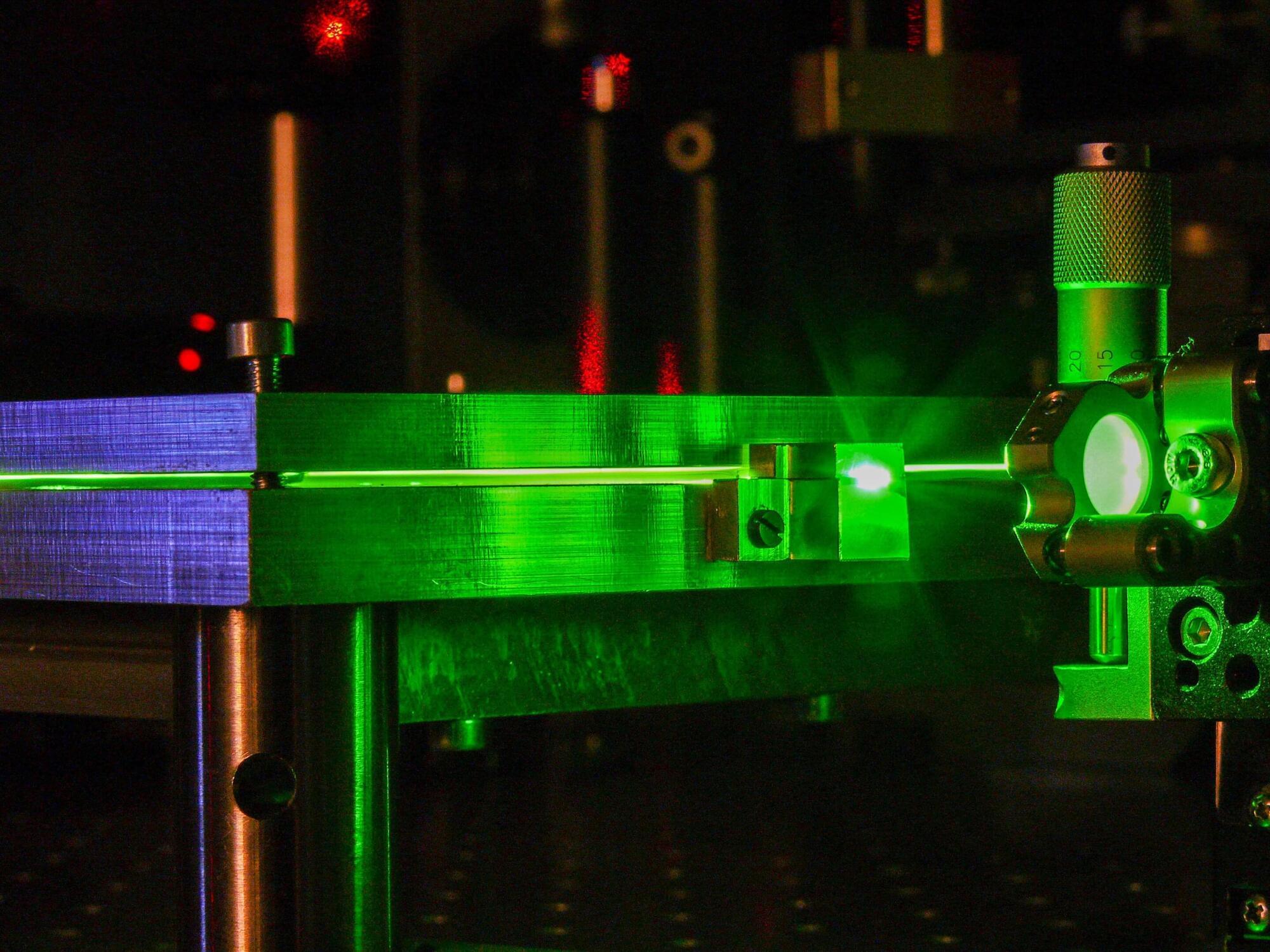

The Mamyshev oscillator (MO) is a type of fiber laser capable of producing high-energy laser pulses at a tunable repetition rate. It is a mode-locked laser which uses light traveling within a closed-loop cavity to produce laser emission. Harmonic mode-locking (HML) is an advanced form of mode-locking process where multiple laser pulses are produced within one round trip of light. MOs employing HML are used for several advanced applications such as optical communication, frequency metrology, and micromachining.

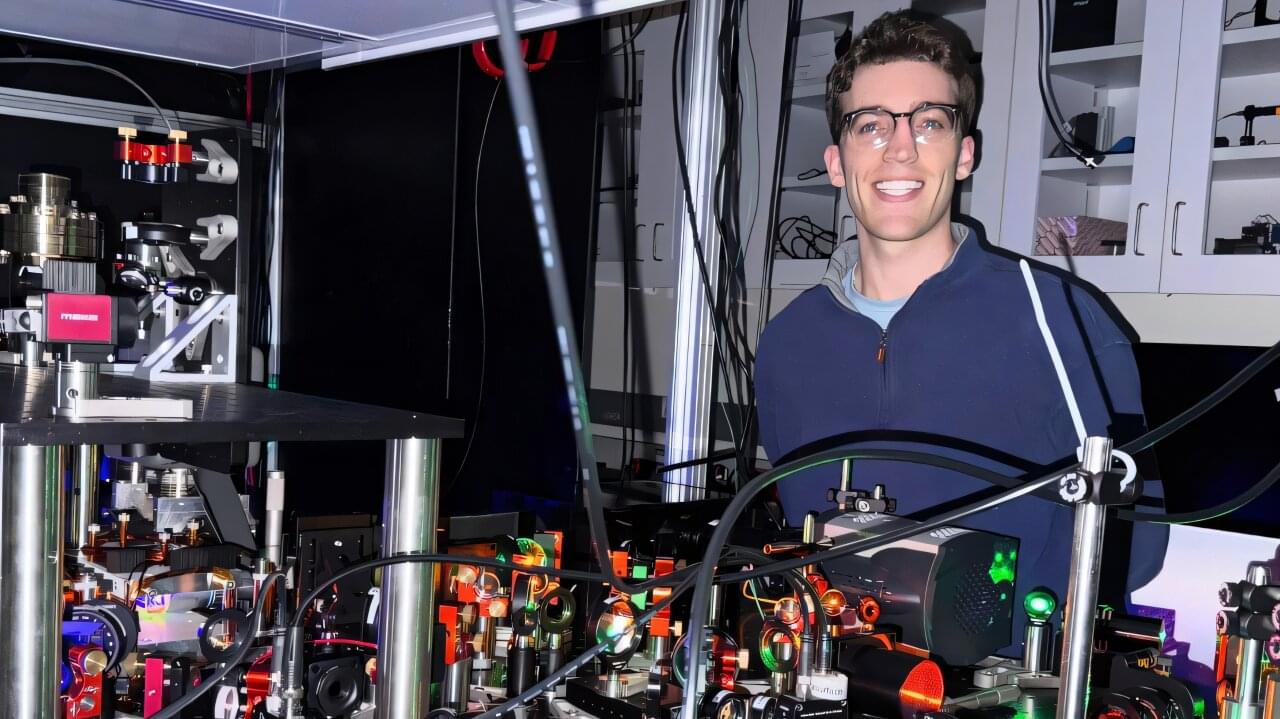

Blink and you might miss it, but if you keep your eye on the monitors in professor Sebastian Will’s lab, you’ll catch a series of single-second flashes that light up the screen. Each flash is an atom of strontium, a naturally occurring alkaline-earth metal, being briefly captured and held in place by “tweezers” made of laser light. “We can see single atoms,” says graduate student Aaron Holman. “Seeing those never gets old.”

The lab saw its first atom at the end of 2022, after two years of constructing the experimental setup—a complicated and carefully calibrated series of atomic sources, vacuum chambers, magnets, electronics, and lasers that trap individual atoms and place them into custom arrangements—from scratch.

Holman, currently a 5th-year Ph.D. student in Physics, helped build the “TweeSr” project, as it’s referred to in the lab, from the ground up. A pure atomic, molecular, and optical (AMO) physicist at heart, he’s now working on ways to turn fundamental research on how atoms, molecules, and light interact into new technologies with collaborators at Columbia Engineering. He’s also heading toward bigger scales as part of a quantum network that is currently under construction.

Two German physicists have unveiled a compact magnet layout that outperforms the famed Halbach array, delivering stronger, more even magnetic fields without bulky superconductors.

Their 3D-printed ring stacks matched analytic predictions and could slash the cost of MRI machines while opening doors for levitation tech and particle accelerators.

Breakthrough in Magnetic Field Generation.