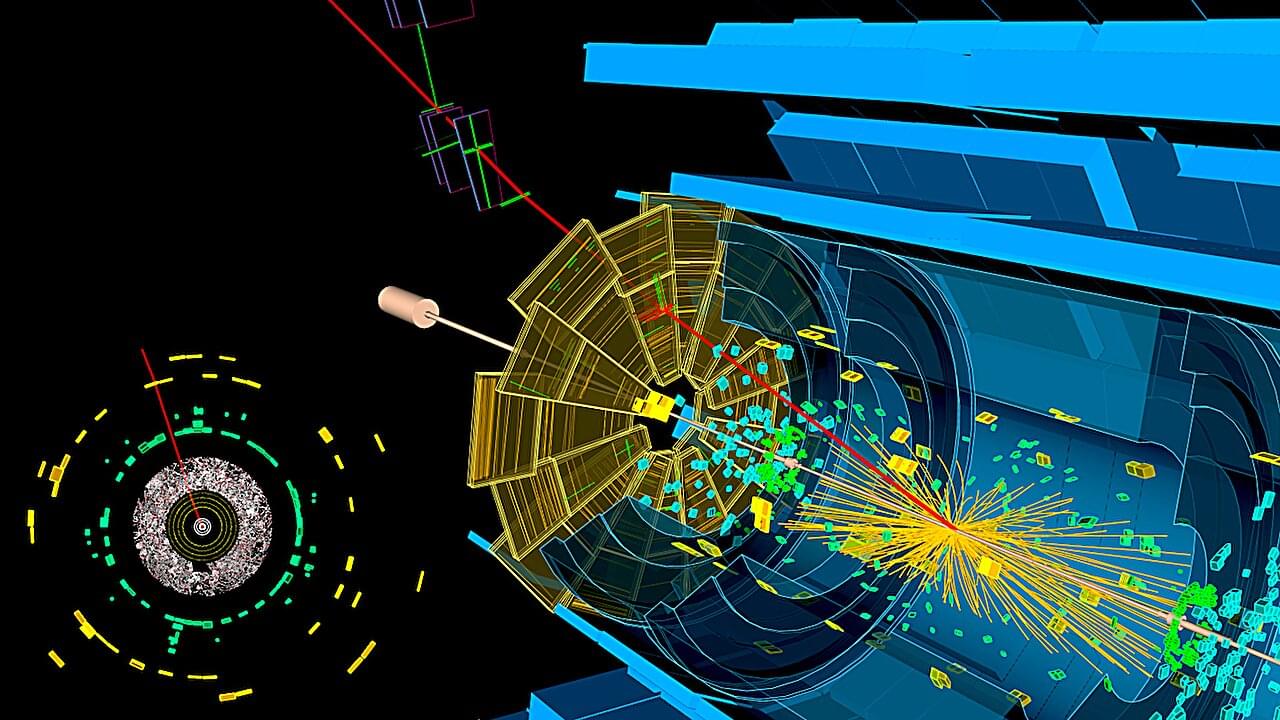

The Large Hadron Collider (LHC) is tough on electronics. Situated inside a 17-mile-long tunnel that runs in a circle under the border between Switzerland and France, this massive scientific instrument accelerates particles close to the speed of light before smashing them together. The collisions yield tiny maelstroms of particles and energy that hint at answers to fundamental questions about the building blocks of matter.

Those collisions produce an enormous amount of data—and enough radiation to scramble the bits and logic inside almost any piece of electronic equipment.

That presents a challenge to CERN’s physicists as they attempt to probe deeper into the mysteries of the Higgs boson and other fundamental particles. Off-the-shelf components simply can’t survive the harsh conditions inside the accelerator, and the market for radiation-resistant circuits is too small to entice investment from commercial chip manufacturers.