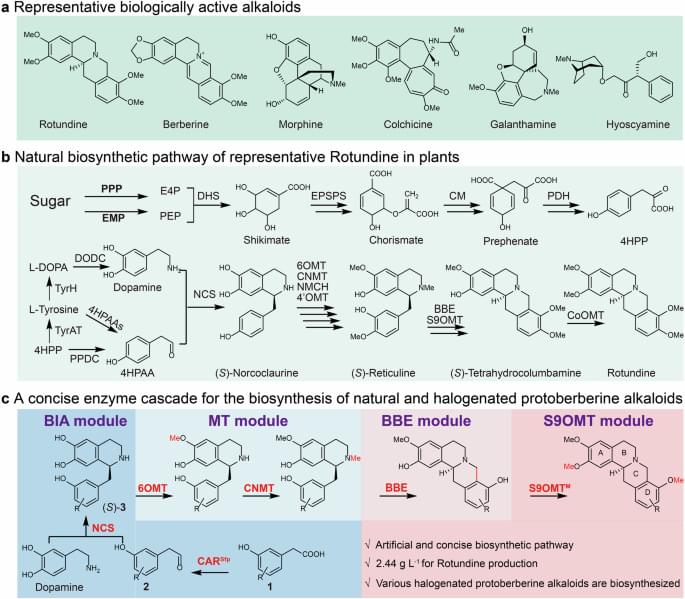

Plant-derived alkaloids are an important class of natural products with various pharmacological properties1,2,3,4, including Rotundine (L-tetrahydropalmatine), berberine, morphine, colchicine, galanthamine and hyoscyamine (Fig. 1a). Many of them have been used as traditional medicines in China, Native America, India and the Islamic region. For instance, Rotundine was first isolated from Corydalis5, a plant that has been used as traditional Chinese herbal medicine for over a thousand years, known for its analgesic, anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective, anti-addictive, and antitumor activities6,7,8. Today, it also serves as an alternative to anxiolytic and sedative drugs from the addictive benzodiazepine group, as well as analgesics9. However, similar to many plant-derived natural products10,11, the commercial use of plant-derived alkaloids still mainly relies on extraction from medicinal plants with low abundance12,13,14,15, which is further affected by climate change, cultivation methods and location. Moreover, due to the lack of appropriate functional groups, derivatization of naturally occurring alkaloids to increase structural complexity and diversity through chemical methods remains challenging, restricting further drug development. Although chemical synthesis methods have been developed to overcome these issues, they often involve harsh conditions and heavy-metal catalysts16,17. In addition, the structural complexity of alkaloids, with their chiral centers and regioselective modifications, often results in low yields.

With the elucidation of the biosynthetic pathways of alkaloids and advancements in synthetic biology18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27, many efforts have been made to biosynthesize natural and unnatural alkaloids in microorganisms, including Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Escherichia coli28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35 (Fig. 1b). However, challenges such as the complexity of their biosynthetic pathways, the difficulties in expressing plant-derived P450 enzyme36,37,38 and berberine bridge enzyme (BBE)29,34,39,40, and the cytotoxicity from the accumulation of alkaloids or its intermediates34,41 always results in low production titers28,29,34, such as 16.9 mg L-1 production in berberine and 68.6 mg L-1 production in Rotundine in engineered yeasts, which still lack commercial viability. In fact, this remains a common manufacturing challenge for the heterologous biosynthesis of many plant-derived alkaloids in microorganisms.

Recently, it was reported that a designed nine-enzyme catalytic cascade enabled the efficient biosynthesis of the HIV drug islatravir42, and therapeutic oligonucleotides could be produced through an enzyme cascade in a single operation43. These seminal examples suggest that the designed enzyme cascades will revolutionize drug synthesis and development. Furthermore, specific enzymes can control the stereo-and chemoselectivity of chiral compounds44,45. Importantly, the use of modular “plug-and-play” strategy allows the easy incorporation or removal of enzymes to tailor the cascade for synthesizing different target compounds46,47, thereby introducing structural complexity and diversity. As for plant-derived natural products, steps catalyzed by enzymes that are difficult to express in engineered cells or that are still not identified can be bypassed through the careful selection of substrates46, making the process more efficient or feasible.