Microbial systems have been synthetically engineered to deploy therapeutic payloads in vivo.

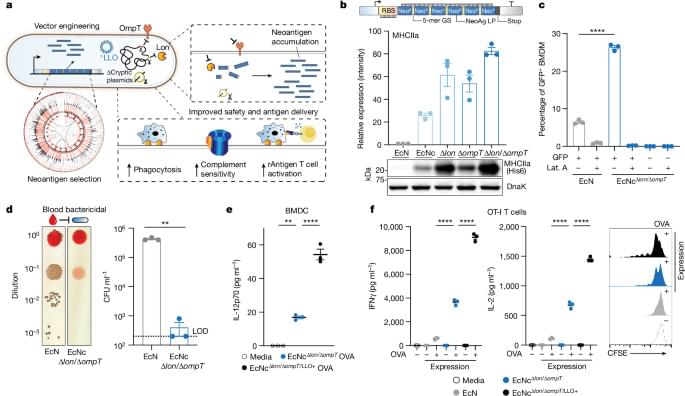

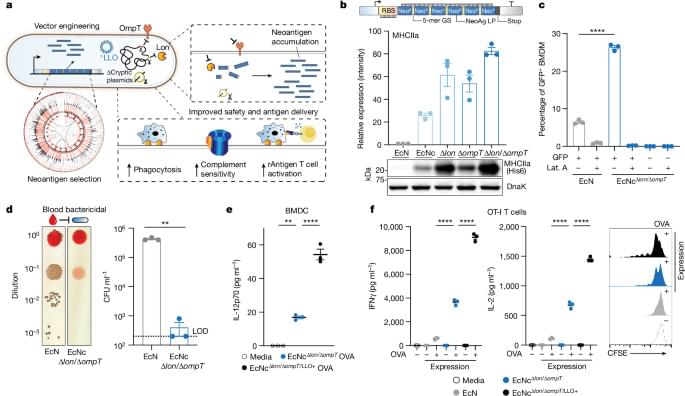

To enable effective cancer vaccination, we developed an engineered bacterial system in probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 (EcN) to enhance expression, delivery and immune-targeting of arrays of tumour exonic mutation-derived epitopes highly expressed by tumour cells and predicted to bind major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and II (Fig. 1a). This system incorporates several key design elements that enhance therapeutic use: optimization of synthetic neoantigen construct form with removal of cryptic plasmids and deletion of Lon and OmpT proteases to increase neoantigen accumulation, increased susceptibility to phagocytosis for enhanced uptake by antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and presentation of MHC class II-restricted antigens, expression of listeriolysin O (LLO) to induce cytosolic entry for presentation of recombinant encoded neoantigens by MHC class I molecules and T helper 1 cell (TH1)-type immunity and improved safety for systemic administration due to reduced survival in the blood and biofilm formation.

To assemble a repertoire of neoantigens, we conducted exome and transcriptome sequencing of subcutaneous CT26 tumours. Neoantigens were predicted from highly expressed tumour-specific mutations using established methods14,15, with selection criteria inclusive of putative neoantigens across a spectrum of MHC affinity16,17. Given the importance of both MHC class I and MHC class II binding epitopes in antitumour immunity15,18,19, we integrated a measure of wild-type-to-mutant MHC affinity ratio—termed agretopicity17,20—for both epitope types derived from a given mutation, to help estimate the ability of adaptive immunity to recognize a neoantigen. Predicted neoantigens were selected from the set of tumour-specific mutations satisfying all criteria, notably encompassing numerous recovered, previously validated CT26 neoantigens15 (Extended Data Fig. 1a).

We then sought to create a microbial system that could accommodate the production and delivery of diverse sets of neoantigens to lymphoid tissue and the tumour microenvironment (TME). For the purpose of assessing neoantigen production capacity, a prototype gene encoding a synthetic neoantigen construct (NeoAgp) was created by concatenating long peptides encompassing linked CD4+ and CD8+ T cell mutant epitopes—previously shown as an optimal form for stimulating cellular immunity21—derived from CT26 neoantigens (Extended Data Fig. 1b and Extended Data Table 1). The construct was cloned into a stabilized plasmid22 under constitutive expression and transformed into EcN; however, both immunoblot and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) assessment showed low production of the prototype construct by EcN across several tested promoters (Extended Data Fig. 1c).