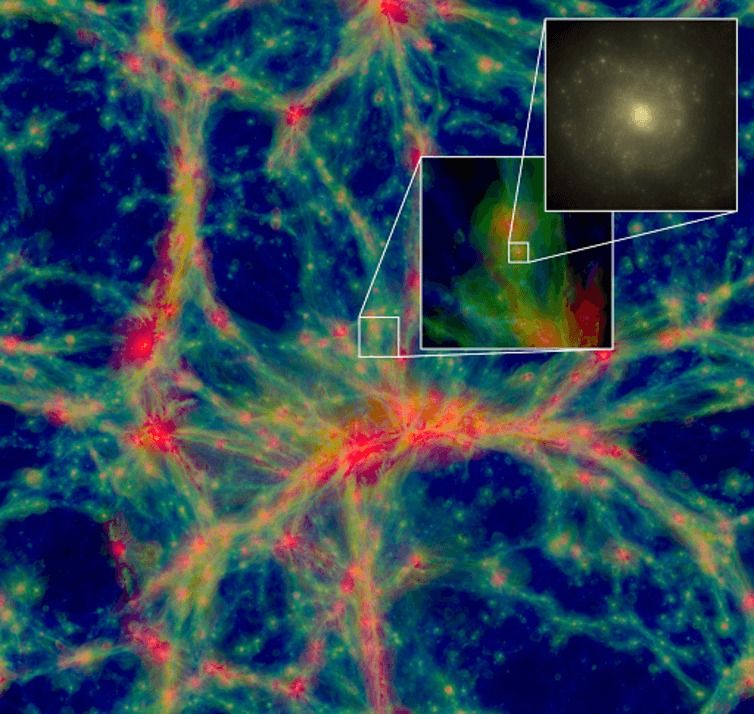

If dark energy is just a grand illusion – as some suggest – then rethinking our interpretation of the basic principles of general relativity in a complex universe is crucial.

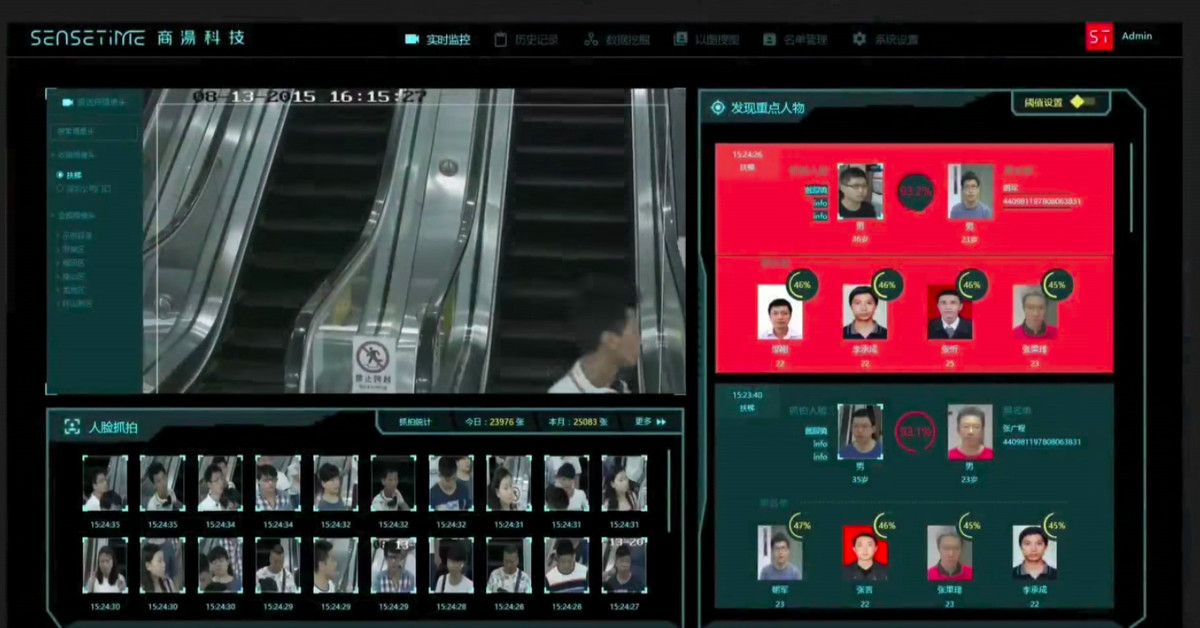

Artificial intelligence is being used for a dizzying array of tasks, but one of the most successful is also one of the scariest: automated surveillance. Case in point is Chinese startup SenseTime, which makes AI-powered surveillance software for the country’s police, and which this week received a new round of funding worth $600 million. This funding, led by retailing giant Alibaba, reportedly gives SenseTime a total valuation of more than $4.5 billion, making it the most valuable AI startup in the world, according to analyst firm CB Insights.

This news is significant for a number of reasons. First, it shows how China continues to pour money into artificial intelligence, both through government funding and private investment. Many are watching the competition between China and America to develop cutting-edge AI with great interest, and see investment as an important measure of progress. China has overtaken the US in this regard, although experts are quick to caution that it’s only one metric of success.

Secondly, the investment shows that image analysis is one of the most lucrative commercial applications for AI. SenseTime became profitable in 2017 and claims it has more than 400 clients and partners. It sells its AI-powered services to improve the camera apps of smartphone-makers like OPPO and Vivo; to offer “beautification” effects and AR filters on Chinese social media platforms like Weibo; and to provide identity verification for domestic finance and retail apps like Huanbei and Rong360.

I have been watching this closely.

By.

Our founder introduces you the new hydropower technology that is going to make hydropower Green again!

Japanese researchers have developed a way of not only levitating, but also moving objects three dimensionally using sound waves. The device uses four arrays of speakers to make soundwaves that intersect at a focal point that can be moved up, down, left, and right using external controls. And to human ears the device is completely quiet, as it uses ultrasound.

Occupational exposure to ultrasound in excess of 120 dB may lead to hearing loss. Exposure in excess of 155 dB may produce heating effects that are harmful to the human body, and it has been calculated that exposures above 180 dB may lead to death.[45] The UK’s independent Advisory Group on Non-ionising Radiation (AGNIR) produced a report in 2010, which was published by the UK Health Protection Agency (HPA). This report recommended an exposure limit for the general public to airborne ultrasound sound pressure levels (SPL) of 70 dB (at 20 kHz), and 100 dB (at 25 kHz and above).

“We shape our tools”, the old maxim goes, “and thereafter our tools shape us.” But what if both man and tools could shape and guide each other — as equals?

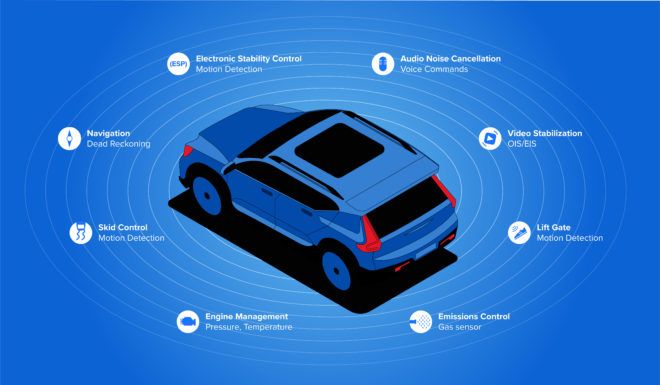

That’s the dream of the Senior Director of Advanced Technology at InvenSense, a TDK Group Company, Dr. Peter G. Hartwell, who believes we are heading into a profound new age of man-machine collaboration, led by breakthroughs in sensor technology. “Some problems simply can’t be solved using human senses or machine capabilities alone; we need a fusion of the two,” says Hartwell.

The problems which Hartwell targets are at the very core of a life well lived: customized health care, more energy-efficient infrastructure, productive workplaces, safer cities, and improved environmental monitoring.