A new story from Inverse with a quote I gave: https://www.inverse.com/article/11766-how-instant-translatio…nd-listens #future

People can save lives when they speak the same language.

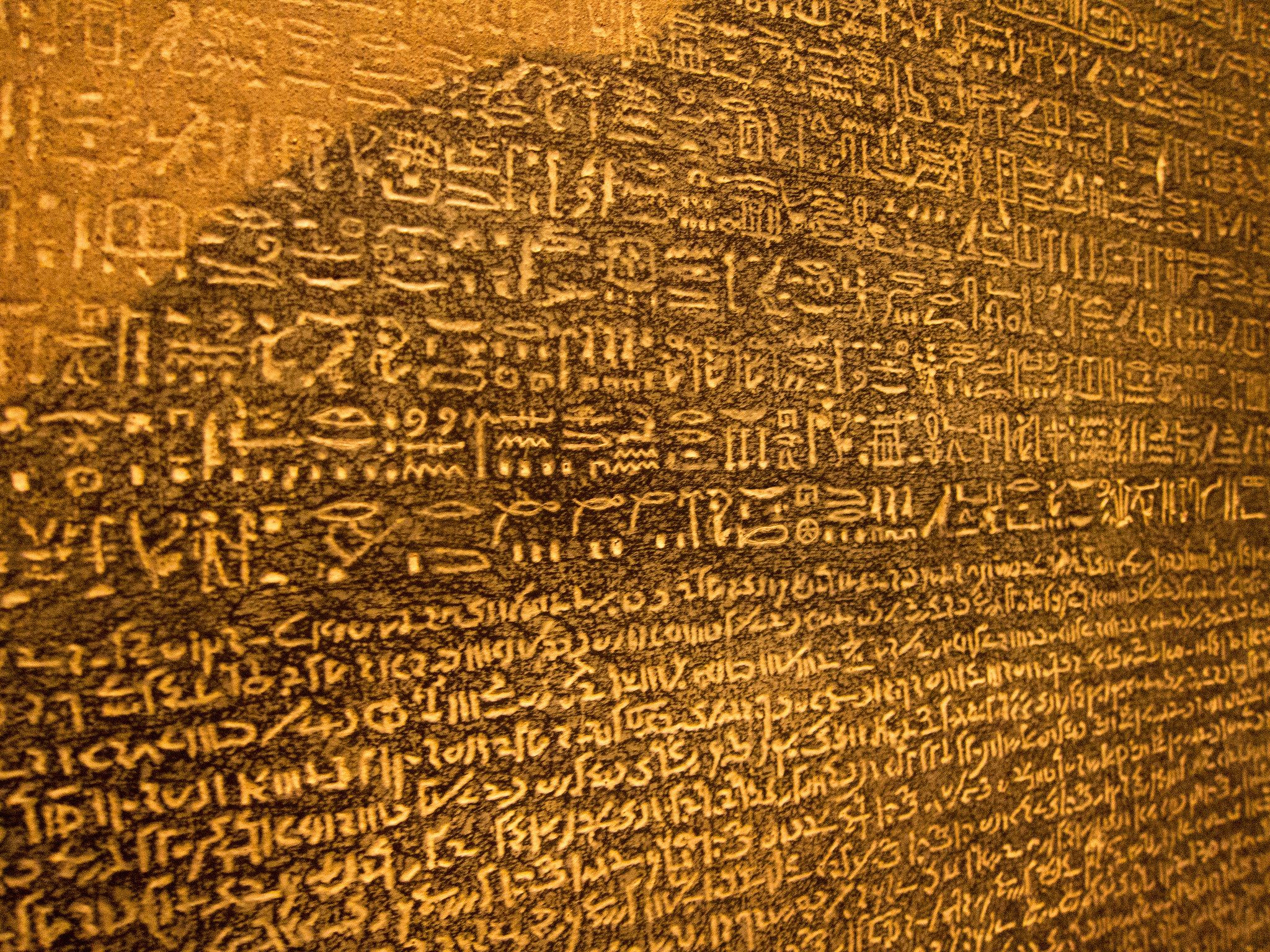

Technology has advanced such that we can instantaneously communicate with people in the farthest reaches of the world without breaking a sweat. Furthermore, we can do so in their own languages without even a single credit hour of exploratory language class. When language tools like Google Translate and Yandex. Translate meet communication apps like Skype and Telegram, the world shrinks in the best way.

Dan Simonson, a computational linguist and Ph.D. candidate at Georgetown University, endorses such language technology as a force for good, and it’s not just because he recently had to find the bathroom while visiting Beijing as a novice Mandarin speaker. “Humanitarian relief efforts are often executed by enlisted soldiers who have neither the time nor the resources to learn the language of where they are assigned to provide relief,” he says. “For these people to have access to even poor translation tools in low-resource languages — ones for which there isn’t a lot of data available to create translation tools — could immediately improve the efficiency of such relief efforts, saving thousands of lives as a result.”

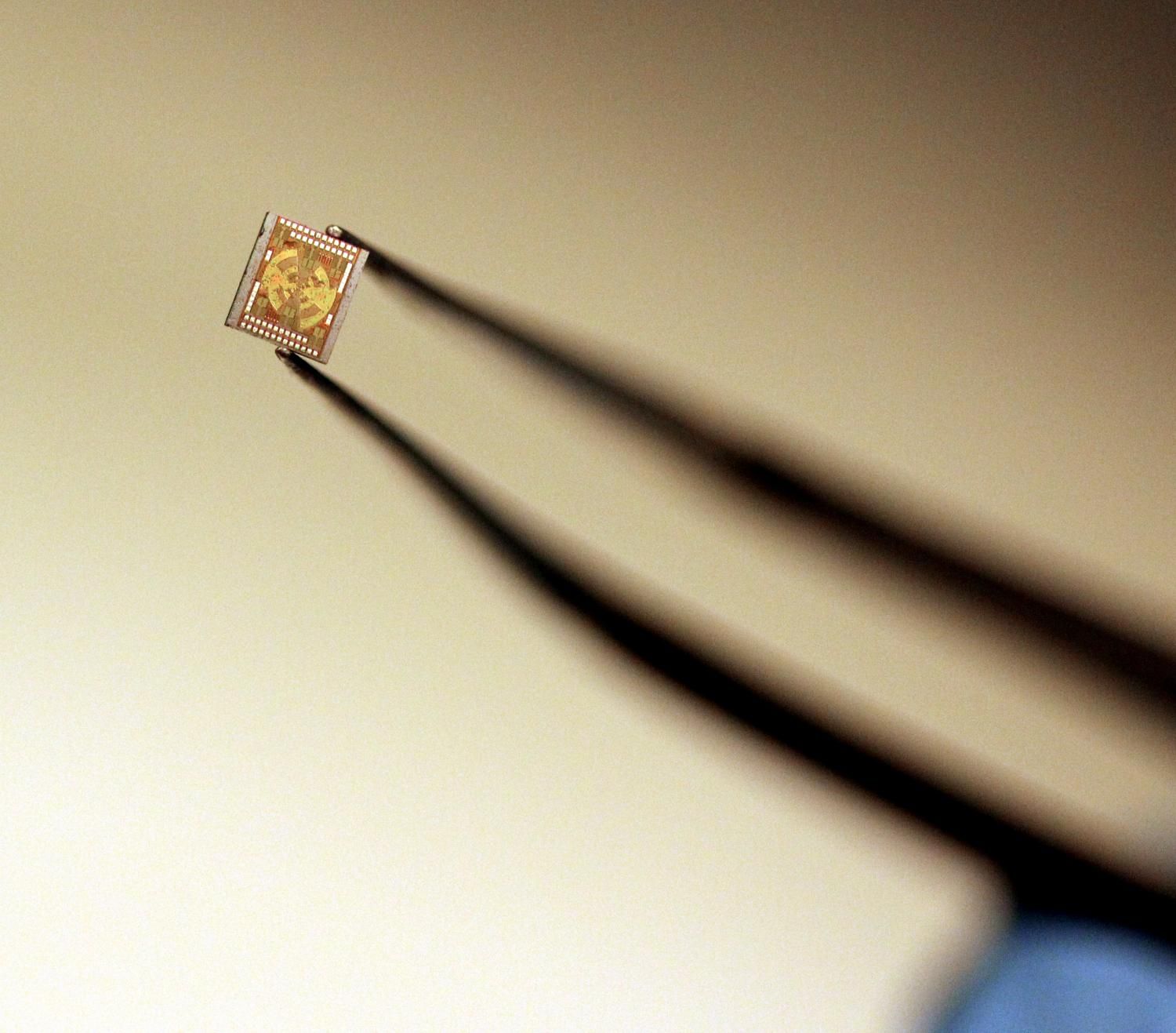

Futurist ideas suggest we’ll see nothing less than a technological facsimile of the Babel fish from The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. This is a living creature from Douglas Adams’ classic sci-fi comedy romp that, when shoved into your ear canal, listens to everything around you and whispers a perfect translation to you in your native language. On a long enough timeline, those with a transhumanist bent say we’ll have electronic Babel fish of our own permanently implanted in our bodies.