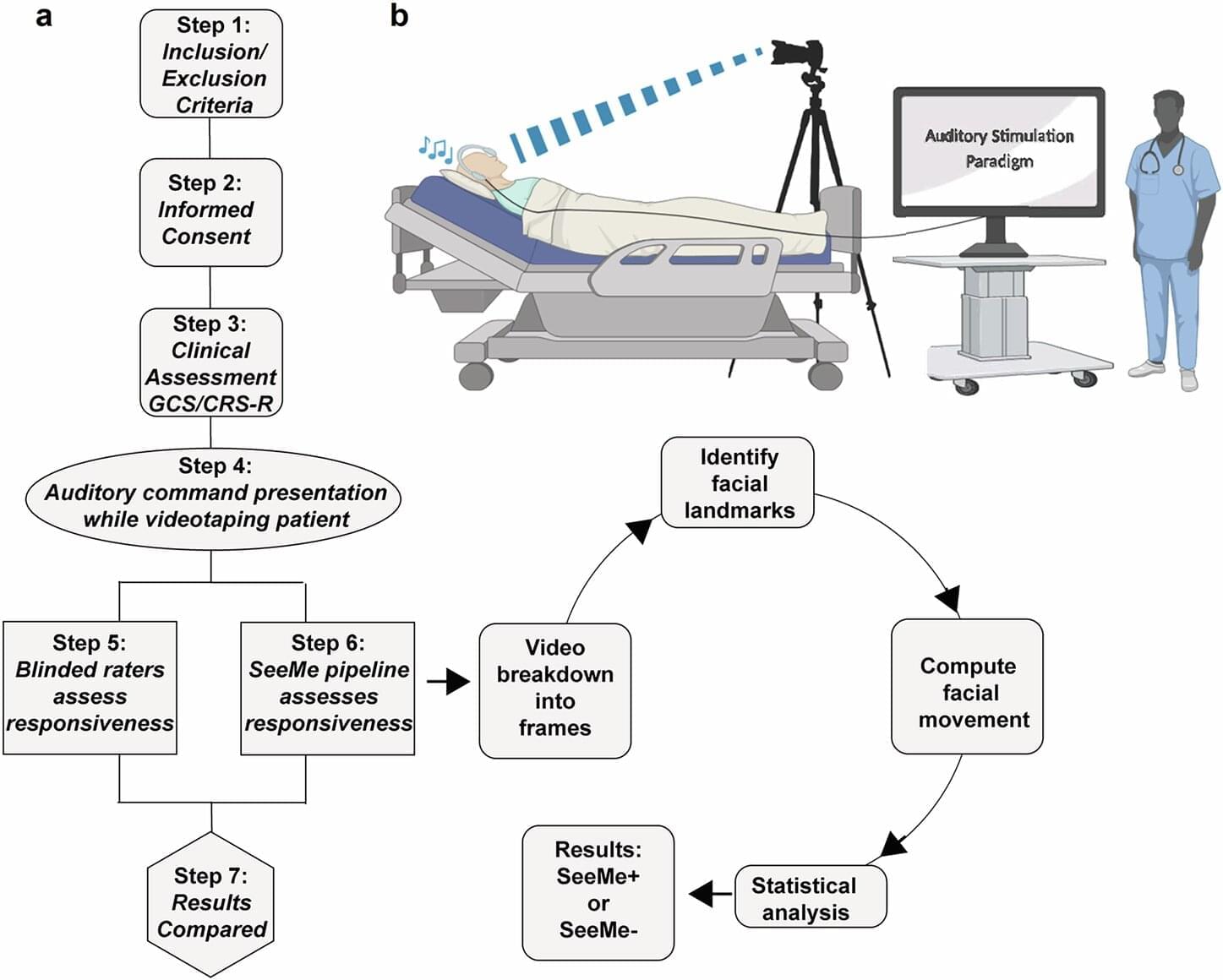

SeeMe, a computer vision tool tested by Stony Brook University researchers, was able to detect low-amplitude, voluntary facial movements in comatose acute brain injury patients days before clinicians could identify overt responses.

Close friends know that I have a standing “do not unplug” order should I ever fall into an unresponsive state. If there is even a flicker of a chance that the mind is still working, I will be fine. Keep me plugged in and hang a “do not disturb” sign on whatever apparatus is keeping me alive.

It’s not like you can know in advance what it’s like, but it seems relaxed enough, with plenty of time to think, and I haven’t really gained anything useful from conversations with other humans in years (aside from my editors who always provide valuable information). If it is at all like sleeping, there might be dreams, so, perchance, that’s what I’d be doing in a comatose state. But for the friends by my bedside, how to be certain that the mind is still flickering?