On a Sunday evening earlier this month, a Stanford professor held a salon at her home near the university’s campus. The main topic for the event was “synthesizing consciousness through neuroscience,” and the home filled with dozens of people, including artificial intelligence researchers, doctors, neuroscientists, philosophers and a former monk, eager to discuss the current collision between new AI and biological tools and how we might identify the arrival of a digital consciousness.

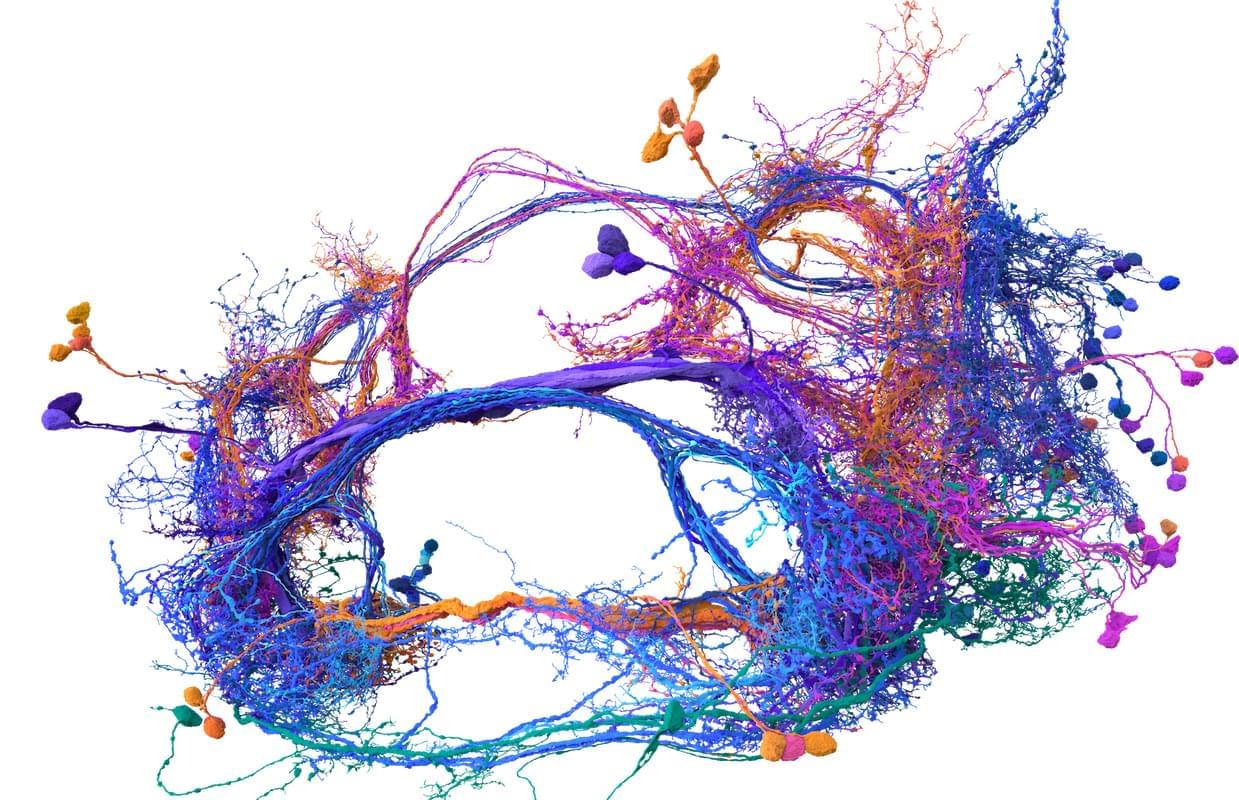

The opening speaker for the salon was Sebastian Seung, and this made a lot of sense. Seung, a neuroscience and computer science professor at Princeton University, has spent much of the last year enjoying the afterglow of his (and others’) breakthrough research describing the inner workings of the fly brain. Seung, you see, helped create the first complete wiring diagram of a fly brain and its 140,000 neurons and 55 million synapses. (Nature put out a special issue last October to document the achievement and its implications.) This diagram, known as a connectome, took more than a decade to finish and stands as the most detailed look at the most complex whole brain ever produced.

Meet Memazing.