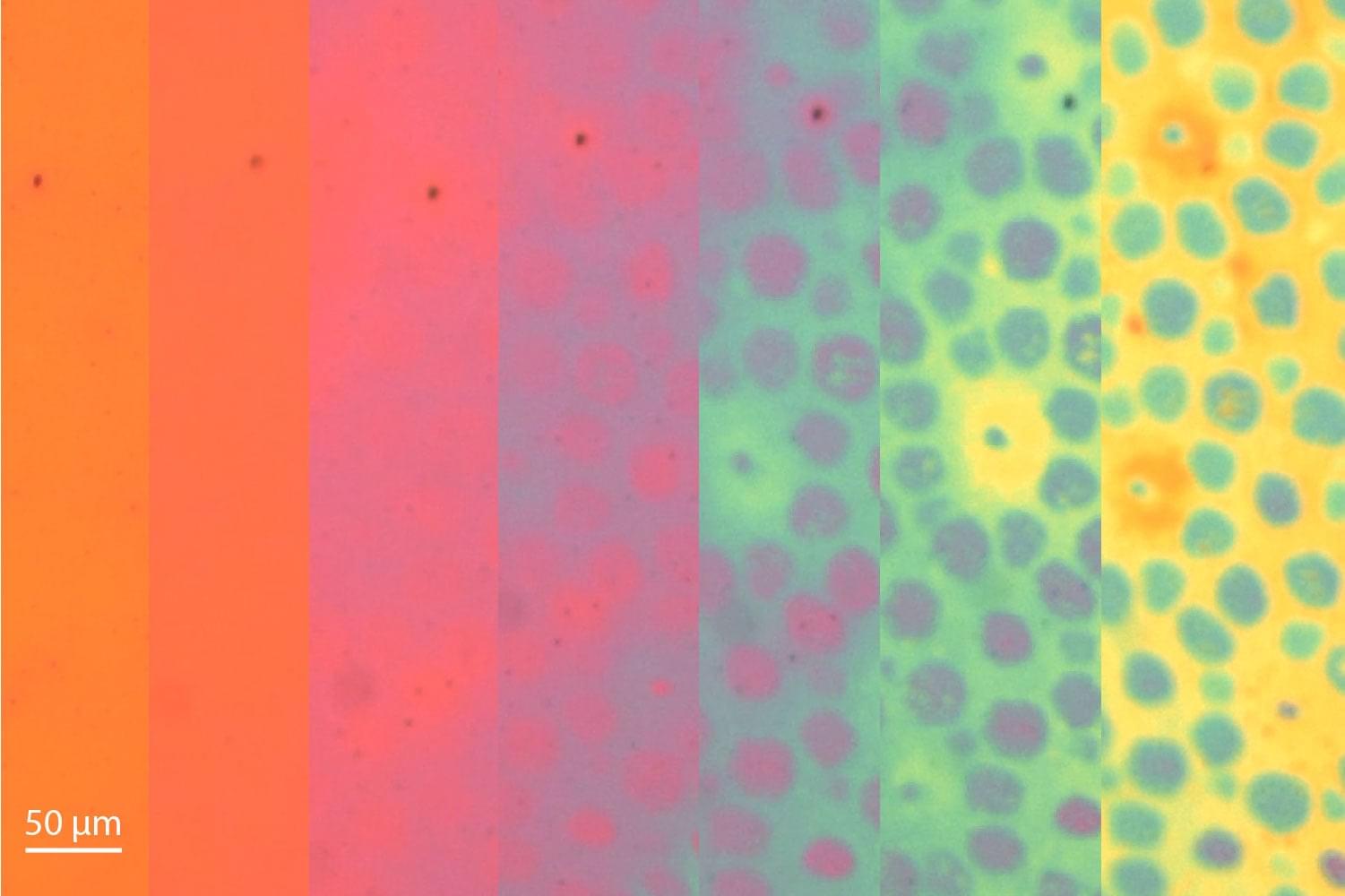

In the fossil record, creatures without hard shells or skeletons, such as jellyfish, are rarely preserved for long periods of time. Preservation is even less likely in sandstone, a rock made of coarse grains that is full of pores and typically forms in environments shaped by strong waves and frequent storms. Despite these challenges, fossils dating to about 570 million years ago tell a very different story. During the Ediacaran period, unusual soft-bodied organisms died on the seafloor, were quickly buried by sand, and were preserved with striking detail.

These remarkable fossils have since been discovered in rock formations across the globe. Researchers are working to understand how the Ediacara Biota could be preserved so clearly, especially as impressions in sandstone, a process rarely seen elsewhere in the fossil record. Solving this puzzle could help clarify a major missing chapter in the history of large, visible life on Earth.

“The Ediacara Biota look totally bizarre in their appearance. Some of them have triradial symmetry, some have spiraling arms, some have fractal patterning,” says Dr. Lidya Tarhan, a paleontologist at Yale University. “It’s really hard when you first look at them to figure out where to place them in the tree of life.”