It’s pretty cheerful-looking for a robot that gives funeral services.

Japan’s largest container line plans to test a remote-controlled vessel across the Pacific Ocean in 2019 as it pursues fully autonomous technology that could disrupt the global shipping industry.

Nippon Yusen K.K. is considering using a large container ship for the test from Japan to North America and a crew will be on standby for safe operations, Hideyuki Ando, a senior general manager at Monohakobi Technology Institute, said in an interview Wednesday. The institute, a unit of Nippon Yusen, conducts research and development in areas such as safe vessel operation, energy saving, and logistics.

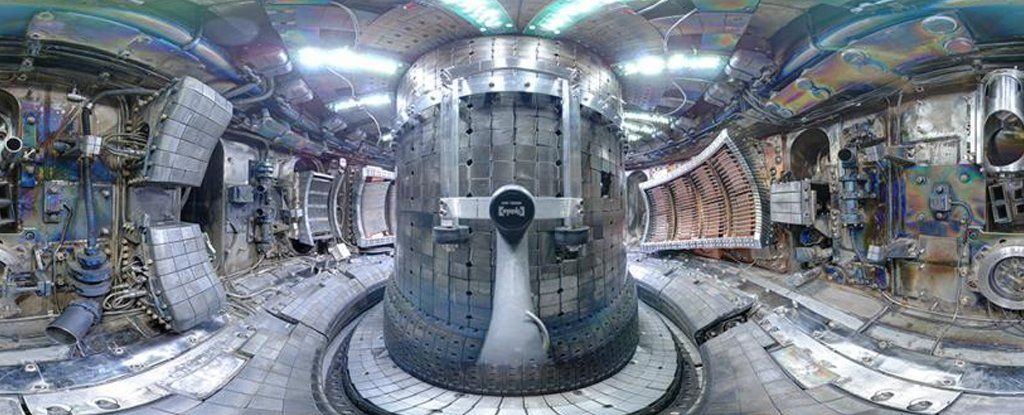

Extracting useful amounts of energy from the merging of atoms is tricky business, not least thanks to the challenges of controlling squirming clouds of ultra-hot plasma.

Our clean power fusion goals could be a step closer now researchers have tweaked their fusion recipe to add a new ion to the mix. This allows researchers to get a better grip on how high-energy charged particles move not just inside reactors on Earth, but potentially provide insights into how they behave in stars.

A team of researchers at MIT have used data from experiments conducted on a type of fusion reactor called a tokamak to explore how adding a third ion to the more traditional two-ion plasma mix shakes things up.

You can go to school for space mining.

GOLDEN, Colo. — The Colorado School of Mines plans to launch a new graduate program that could help people inhabit other planets some day.

The school is working to launch the space resources graduate program that will teach students how to explore, extract and use resources not only on Earth but also on the moon, Mars, asteroids and more.

The school said the classes will focus on scientific, technical, economic, policy and legal aspects of the field.

What if traffic flowed through our streets as smoothly and efficiently as blood flows through our veins? Transportation geek Wanis Kabbaj thinks we can find inspiration in the genius of our biology to design the transit systems of the future. In this forward-thinking talk, preview exciting concepts like modular, detachable buses, flying taxis and networks of suspended magnetic pods that could help make the dream of a dynamic, driverless world into a reality.

“Some people are obsessed by French wines. Others love playing golf or devouring literature. One of my greatest pleasures in life is, I have to admit, a bit special. I cannot tell you how much I enjoy watching cities from the sky, from an airplane window.”

Point discussed at 1:31 in the video: https://youtu.be/VJ_qtKf64Is?t=1m3s

From the conference text at: https://www.academia.edu/34323947/Mont_Order_July_2017_Conference_Text

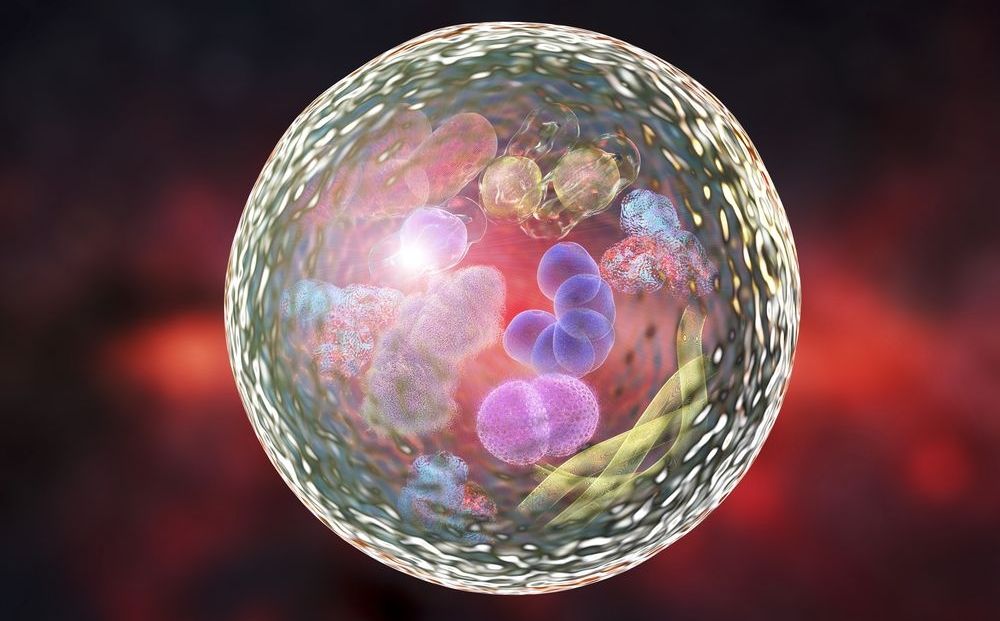

Autophagy means “eating of self” (“auto”= self; “phag” = eating)[1]. Although its name might sound harmful, autophagy appears to have longevity-promoting effects[2]. Here, we will explain what autophagy is, how it works, its benefits, and how it plays a role in aging.

What is Autophagy?

Autophagy is the way cells break down misbehaving or nonfunctional organelles and proteins in the cell[1,2]. This means autophagy can consume organelles such as, mitochondria, peroxisomes, and the endoplasmic reticulum[1].