Sophia is Hanson Robotics’ most advanced robot. After receiving her citizenship, she was interviewed by Andrew Ross Sorkin in Riyadh. During the course of her interview, she took a dig at Elon Musk and Hollywood movies for portraying the artificial intelligence in a questionable light.

Scientists are altering a powerful gene-editing technology in hopes of one day fighting diseases without making permanent changes to people’s DNA.

The trick: Edit RNA instead, the messenger that carries a gene’s instructions.

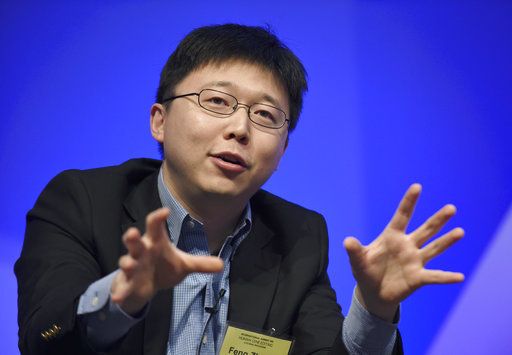

“If you edit RNA, you can have a reversible therapy,” important in case of side effects, said Feng Zhang of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, a gene-editing pioneer whose team reported the new twist Wednesday in the journal Science.

Neat!

Drawing in air, touchless control of virtual objects, and a modular mobile phone with snap-in sections (for lending to friends, family members, or even strangers) are among the innovative user-interface concepts to be introduced at the 30th ACM User Interface Software and Technology Symposium (UIST 2017) on October 22–25 in Quebec City, Canada.

Here are three concepts to be presented, developed by researchers at Dartmouth College’s human computer interface lab.

Elena Milova shares her #IAmTheLifespan story for Longevity Month. Tell us your story too!

https://www.leafscience.org/longevity-month-2017-tell-us-your-story/

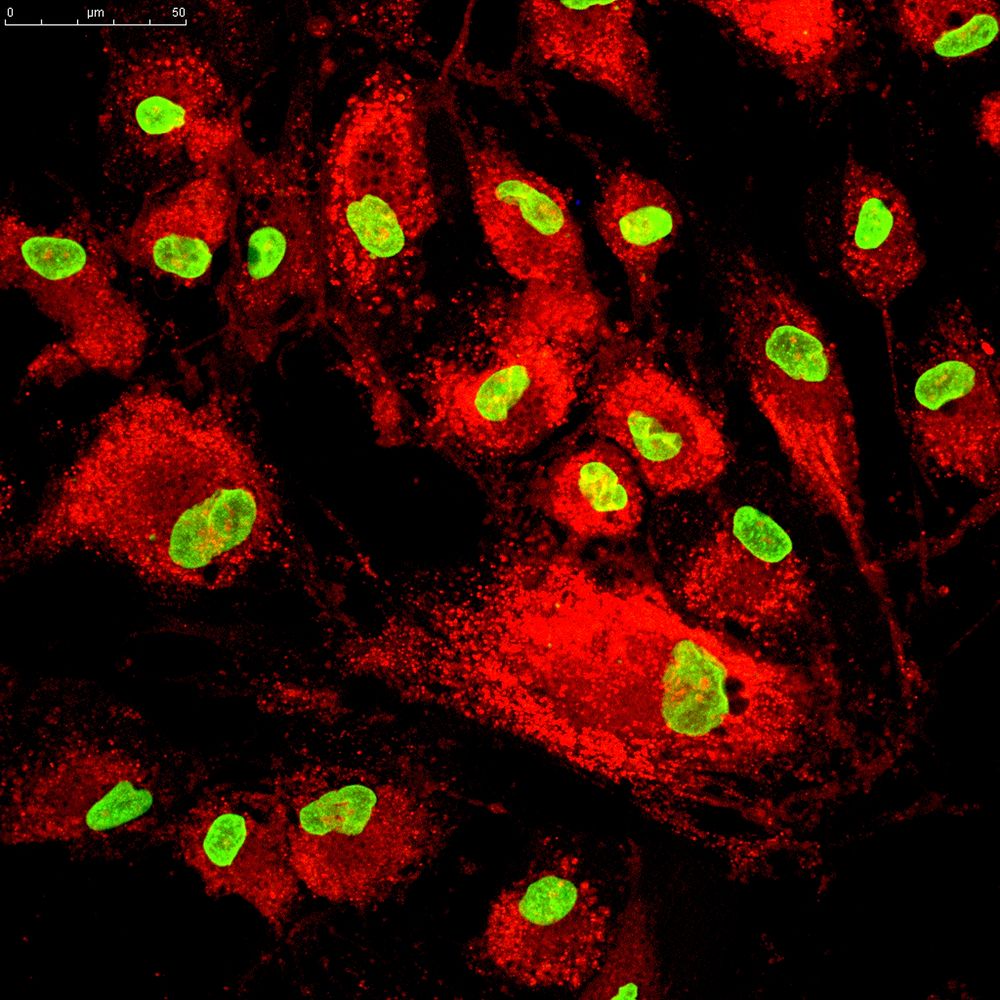

One of the most defining scientific discoveries in recent decades is the development of induced pluripotent stem cells, which lets scientists revert adult cells back into an embryonic-like blank state and then manipulating them to become a particular kind of tissue.

But now a new model could do away with this time-consuming process, taking out the middle step and directly programming cells to become whatever we want them to be.

“Cells in our body always self-specialise,” explains bioinformatics researcher Indika Rajapakse from the University of Michigan.

The first results of two human clinical trials using stem cell therapy for age-related frailty have been published, and the results are very impressive indeed. The studies show that the approach used is effective in tackling multiple key age-related factors.

Aging research has made significant progress in the last few years, with senescent cell clearing therapies entering human trials this year, DNA repair in human trials, and a number of other exciting therapies nearing human testing. We are reaching the point where therapies that target aging processes are no longer a matter of speculation; they are now an undeniable matter of fact.

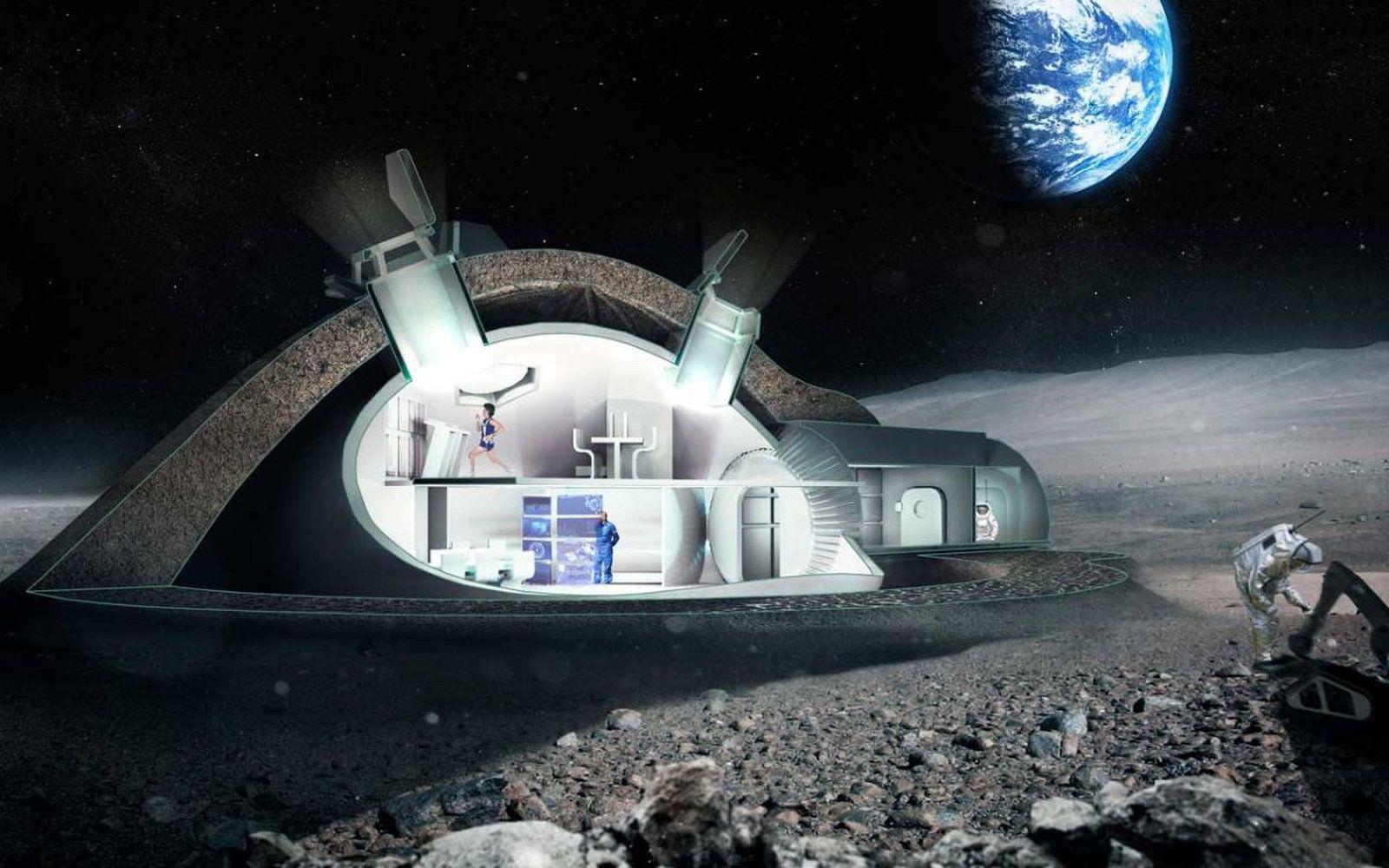

Human settlement of the moon may go through Hawaii.

Earlier this month, an International MoonBase Summit (IMS) brought together representatives from academia, government and the private sector to help lay the groundwork for a base on the lunar surface.

“Because of its geography, geology and culture, Hawaii is the perfect place to build a MoonBase prototype,” said Henk Rogers, an entrepreneur based in Hawaii and the organizer of the IMS. [Lunar Colony: How to Build a Moonbase in Images].