The two million event goers won’t be able to Naruto-run past this.

Facebook has removed a mega-viral event called “Storm Area 51,” claiming it violated community standards. Before it was removed, the tongue-in-cheek event amassed more than 2 million Facebook users, grabbing the attention of the mainstream media.

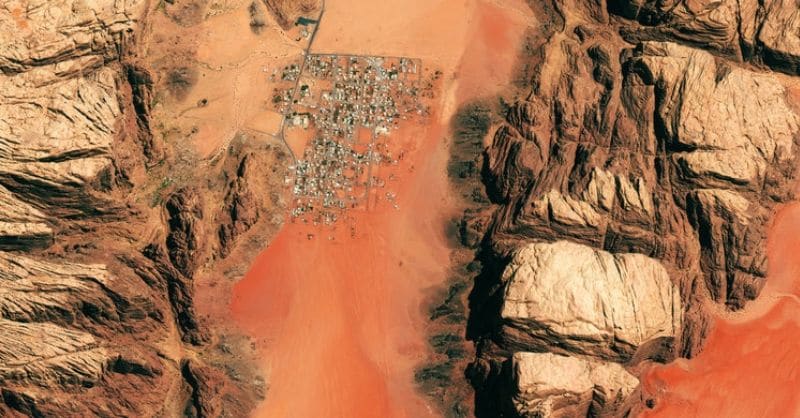

The idea, according to the even description, was to invite an army of memelords and alien enthusisasts to raid the top-secret Air Force military base in the middle of Nevada’s desert. “Let’s see them aliens,” the event description read.

Area 51 has long been the subject of wild speculation and alien conspiracy theories. The 5,000 square mile base has hosted hundreds of nuclear weapons tests and has served as testing grounds for a range of new stealth aircraft.