A new model captures how impurities affect jets formed when bubbles rise and pop at a liquid surface.

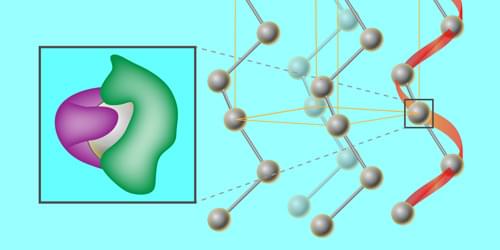

A new framework for studying chiral materials puts the emphasis on electron chirality rather than on the asymmetry of the atomic structure.

Chirality is a fundamental feature of nature, manifesting across scales—from elementary particles and molecules to biological organisms and galaxy formation. An object is considered chiral if it cannot be superimposed on its mirror image. In condensed-matter physics, chirality is primarily viewed as a structural asymmetry in the spatial arrangement of atoms within a crystal lattice [1]. A perhaps less familiar fact is that chirality is also a fundamental quantum property of individual electron states [2]. Now, Tatsuya Miki from Saitama University in Japan and colleagues introduce electron chirality as a framework to quantify symmetry breaking in solids, focusing on chiral and related axial materials [3]. The researchers propose a way of measuring electron chirality with photoemission spectroscopy.

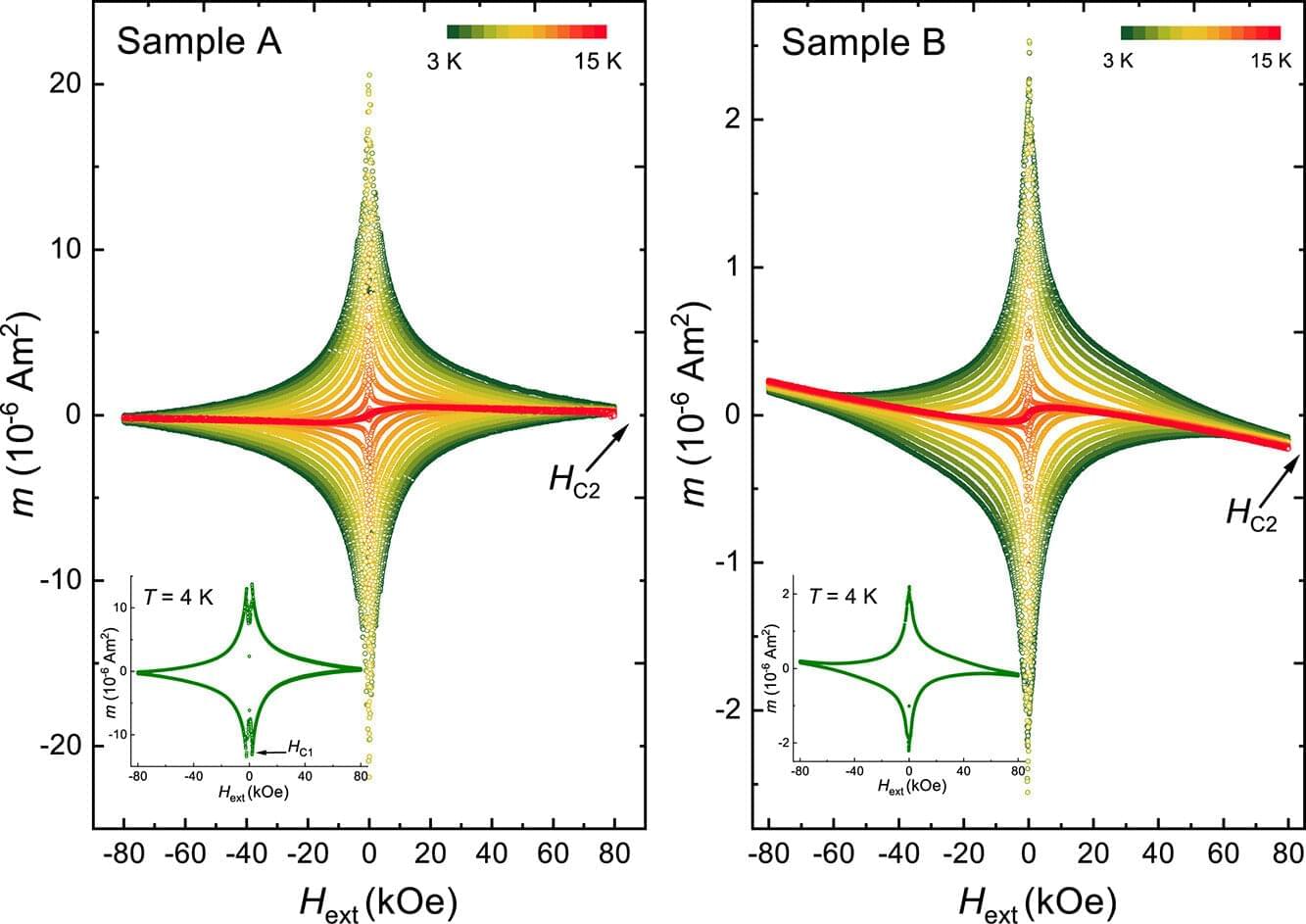

A project led by the University of Melbourne’s Dr. Manjith Bose and Professor Jeff McCallum, who are also members of the ARC Center of Excellence for Quantum Computation and Communication Technology, has identified a promising class of superconductors that may potentially avoid the need for high levels of cryogenic cooling. These advanced materials can be manufactured, be integrable and be compatible using standard silicon and superconducting electronics approaches.

To optimize the growth of these silicide superconductors, Dr. Bose and Prof. McCallum are making extensive use of high–temperature neutron reflectometry on the Spatz reflectometer at ANSTO’s Australian Center for Neutron Scattering.

Neutrons are an ideal tool for exploring extreme sample environments, such as the high pressure, temperatures or fields that are present when manufacturing circuit elements. This is because neutrons can penetrate through most common metals, allowing one to see reflective thin films deep inside furnaces, magnets and cryo-chambers.

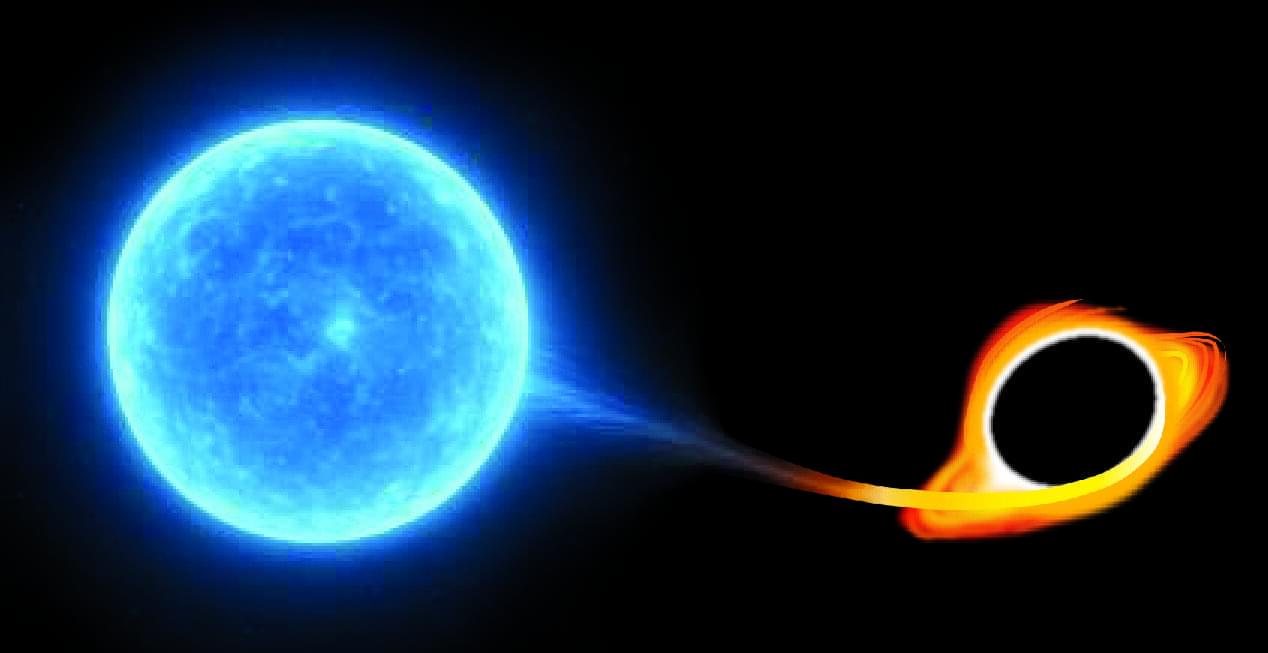

Astronomers from the University of Hawaiʻi’s Institute for Astronomy (IfA) have discovered the most energetic cosmic explosions yet discovered, naming the new class of events “extreme nuclear transients” (ENTs). These extraordinary phenomena occur when massive stars—at least three times heavier than our sun—are torn apart after wandering too close to a supermassive black hole. Their disruption releases vast amounts of energy visible across enormous distances.

The team’s findings appear in the journal Science Advances.

“We’ve observed stars getting ripped apart as tidal disruption events for over a decade, but these ENTs are different beasts, reaching brightnesses nearly ten times more than what we typically see,” said Jason Hinkle, who led the study as the final piece of his doctoral research at IfA. “Not only are ENTs far brighter than normal tidal disruption events, but they remain luminous for years, far surpassing the energy output of even the brightest known supernova explosions.”

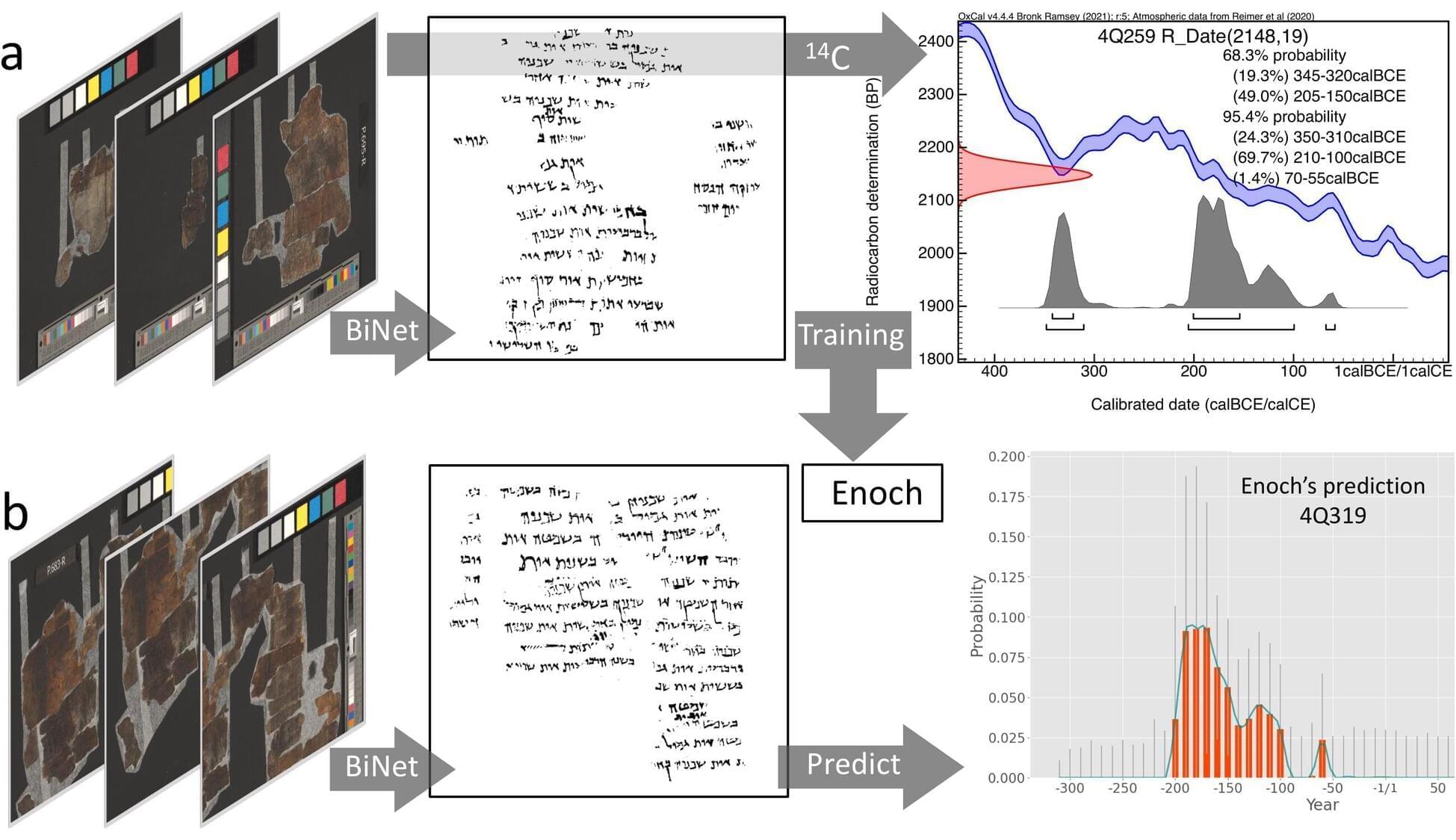

Since their discovery, the historically and biblically hugely important Dead Sea Scrolls have transformed our understanding of Jewish and Christian origins. However, while the general date of the scrolls is from the third century BCE until the second century CE, individual manuscripts thus far could not be securely dated.

Now, by combining radiocarbon dating, paleography, and artificial intelligence, an international team of researchers led by the University of Groningen has developed a date-prediction model, called Enoch, that provides much more accurate date estimates for individual manuscripts on empirical grounds.

Using this model, the researchers demonstrate that many Dead Sea Scrolls are older than previously thought. And for the first time, they establish that two biblical scroll fragments come from the time of their presumed biblical authors. They present their results in the journal PLOS One.

A trio of AI researchers at KAIST AI, in Korea, has developed what they call a Chain-of-Zoom framework that allows the generation of extreme super-resolution imagery using existing super-resolution models without the need for retraining.

In their study published on the arXiv preprint server, Bryan Sangwoo Kim, Jeongsol Kim, and Jong Chul Ye broke down the process of zooming in on an image and then used an existing super-resolution model at each step to refine the image, resulting in incremental improvements in resolution.

The team in Korea began by noting that existing frameworks for improving the resolution of pictures tend to use interpolation or regression when zooming, resulting in blurry imagery. To overcome these problems, they took a new approach—using a stepwise zooming process, in which subsequent steps improve on those that came before.

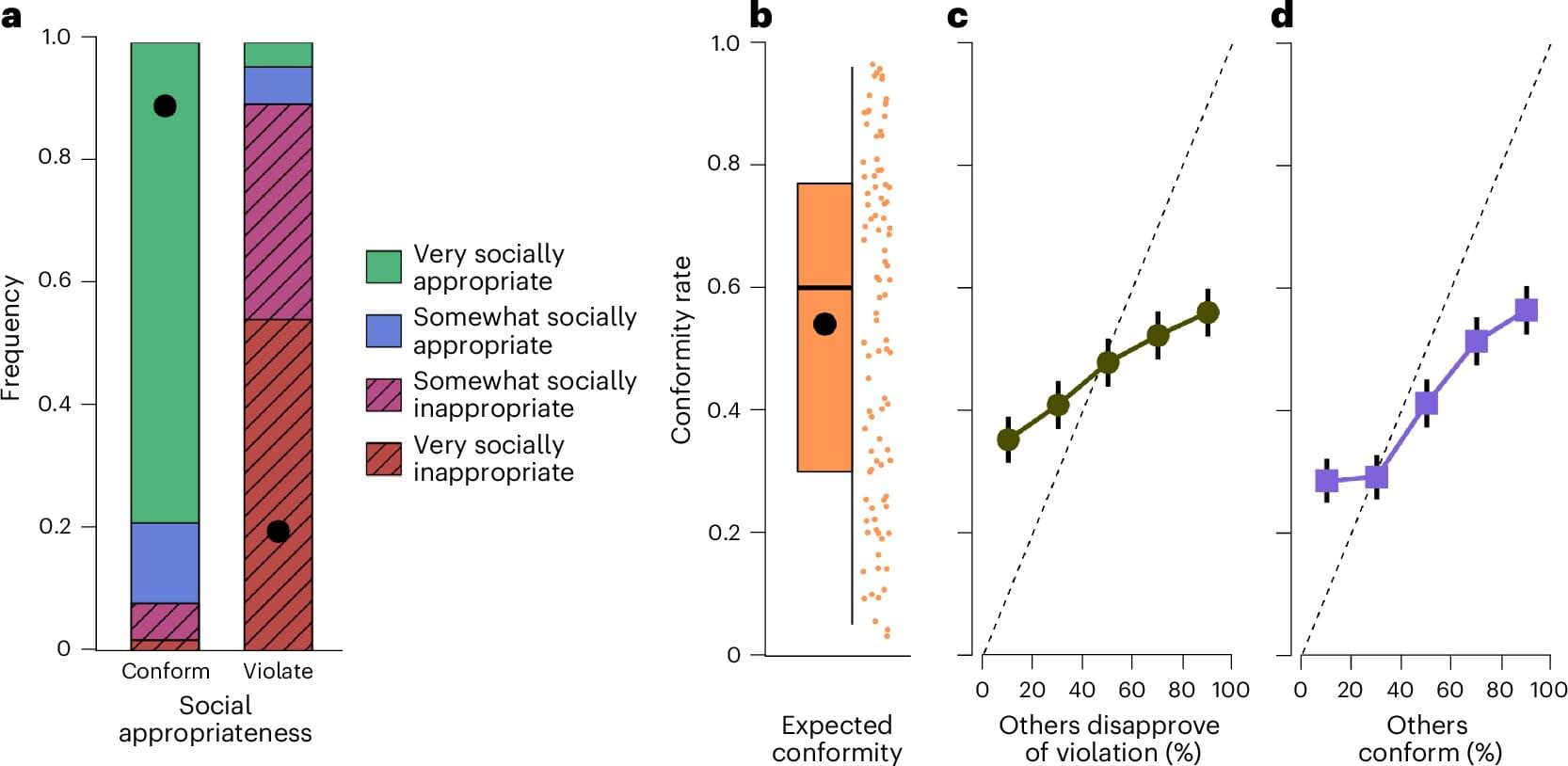

Contrary to the popular saying, rules aren’t meant to be broken, as they are foundational to society and exist to uphold safety, fairness and order in the face of chaos. The collective benefits of rule-following are well established, but individual incentives are often unclear. Yet, people still comply, and the reasons why are pieces of a puzzle that researchers of human behavior have been trying to piece together for years.

A recent study published in Nature Human Behavior explored the behavioral principles behind why people follow rules using a newly designed framework called CRISP. A series of four online experiments based on the framework involving 14,034 English-speaking participants, revealed that the majority (55%–70%) of participants chose to follow arbitrary rules—even when the compliance was costly, they were anonymous and violations had no adverse effects on others.

This proposed CRISP system explains rule conformity © as a function of four components: R—intrinsic respect for rules, independent of others’ behavior; I—extrinsic incentives, such as the threat of punishment for breaking rules; S—social expectations about whether others will follow the rule or believe one should; and P—social preferences, which matter when rule-following affects the well-being of others.

The extraction of work (i.e., usable energy) from quantum processes is a key focus of quantum thermodynamics research, which explores the application of thermodynamics laws to quantum systems. Meanwhile, other quantum physics research has been investigating the non-Markovian dynamics of open quantum systems, which entail the influence of past states on the systems’ future evolution.

Researchers at the University of Nottingham and University of São Paulo have introduced a general and rigorous framework that bridges quantum thermodynamics and non-Markovian dynamics, showing that the latter could serve as a resource that can be exploited to enhance the extraction of work from quantum processes.

Their paper, published in Physical Review Letters, could open new possibilities for the future development of quantum technologies.

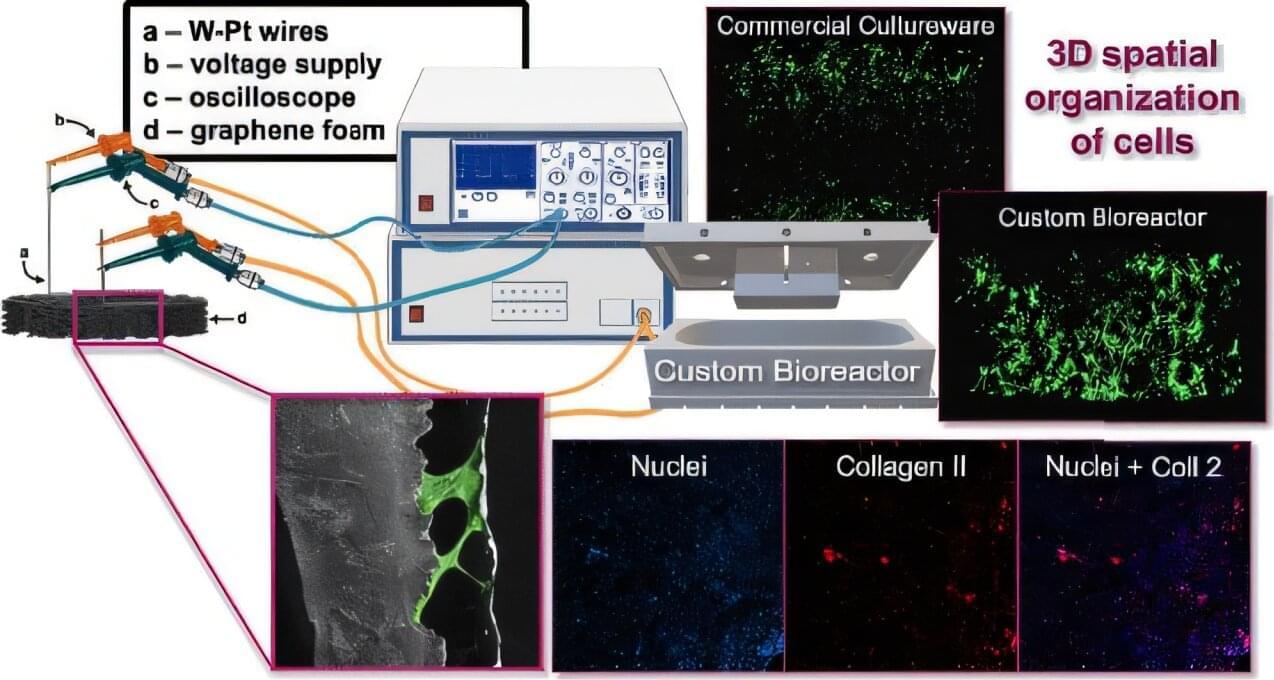

Boise State University researchers have developed a new technique and platform to communicate with cells and help drive them toward cartilage formation. Their work leverages a 3D biocompatible form of carbon known as graphene foam and is featured on the cover of Applied Materials and Interfaces.

In this work, the researchers aim to develop new techniques and materials that can hopefully lead to new treatments for osteoarthritis through tissue engineering. Osteoarthritis is driven by the irreversible degradation of hyaline cartilage in the joints, which eventually leads to pain and disability, with complete joint replacement being the standard clinical treatment. Using custom-designed and 3D-printed bioreactors with electrical feedthroughs, they were able to deliver brief daily electrical impulses to cells being cultured on 3D graphene foam.

The researchers discovered that applying direct electrical stimulation to ATDC5 cells adhered to the 3D graphene foam bioscaffolds significantly strengthens their mechanical properties and improves cell growth —key metrics for achieving lab-grown cartilage. ATDC5 cells are a murine chondrogenic progenitor cell line well studied as a model for cartilage tissue engineering.

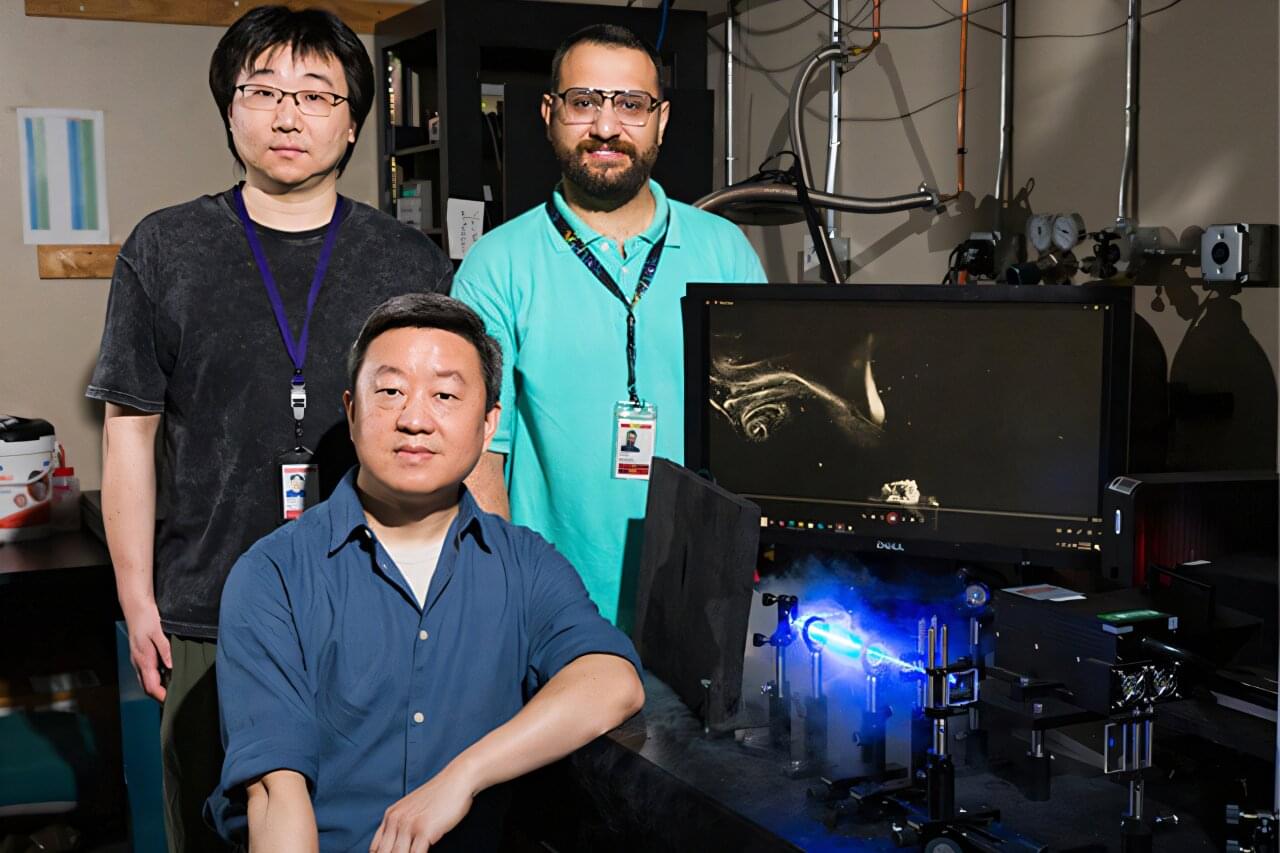

An international research collaboration featuring scientists from the FAMU-FSU College of Engineering and the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory has discovered a fundamental universal principle that governs how microscopic whirlpools interact, collide and transform within quantum fluids, which also has implications for understanding fluids that behave according to classical physics.

The study, which was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, revealed new insights into vortex dynamics within superfluid helium, a remarkable liquid that exhibits zero-resistance flow at temperatures approaching absolute zero. The research demonstrates that when these quantum vortices intersect and reconnect, they separate faster than their initial approach velocity, creating bursts of energy that characterize turbulence in both quantum and classical fluids.

“Superfluids offer a uniquely clear perspective on turbulence,” said FAMU-FSU College of Engineering Professor Wei Guo, a study co-author. “We’re beginning to understand the universal physics that connects quantum and classical worlds, and that’s an exciting frontier for both science and technology.”