Researchers have created a new ultra-strong carbon called MAC, eight times stronger than graphene, opening the door to durable technologies.

As the opioid epidemic persists across the United States, a team of researchers from Brown University has developed new diagnostic techniques for detecting opioid compounds in adults with opioid use disorder and infants with neonatal abstinence syndrome.

The new techniques, described in two recently published research studies, could equip health care workers with powerful new tools for more effectively treating conditions related to opioid exposure, the researchers say.

In a study published in Scientific Reports, the researchers describe a method that can rapidly detect six different opioid compounds from a tiny amount of serum—no more than a finger prick.

A major medical breakthrough is giving new hope to those with Parkinson’s disease. Stem cell transplants into the brain are showing impressive results, leading to long-term improvements in motor symptoms for the first patients treated… Read more

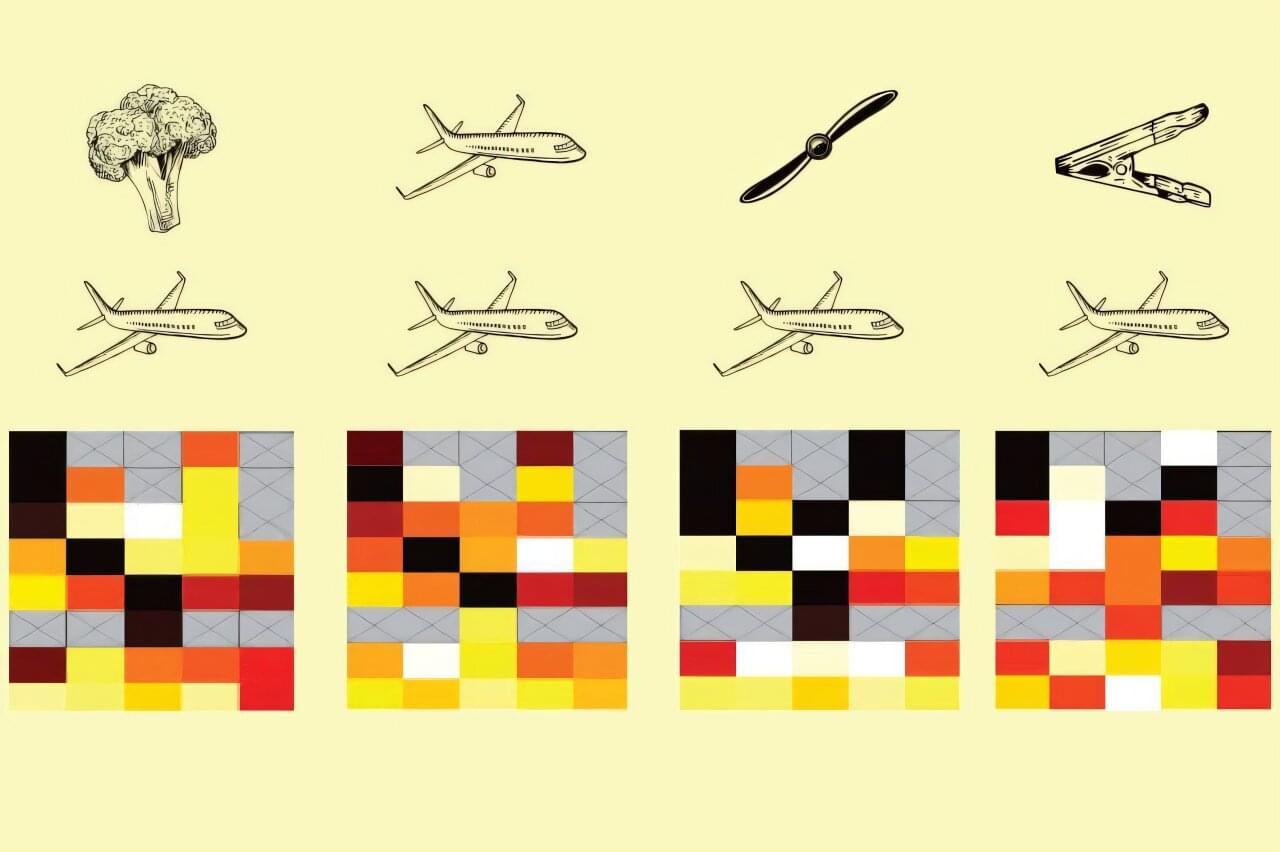

Our brains begin to create internal representations of the world around us from the first moment we open our eyes. We perceptually assemble components of scenes into recognizable objects thanks to neurons in the visual cortex.

This process occurs along the ventral visual cortical pathway, which extends from the primary visual cortex at the back of the brain to the temporal lobes.

It’s long been thought that specific neurons along this pathway handle specific types of information depending on where they are located, and that the dominant flow of visual information is feedforward, up a hierarchy of visual cortical areas. Although the reverse direction of cortical connections, often referred to as feedback, has long been known to exist, its functional role has been little understood.

Two companies are coming together to develop the world’s first infinity train in hope of cutting down on carbon emissions.

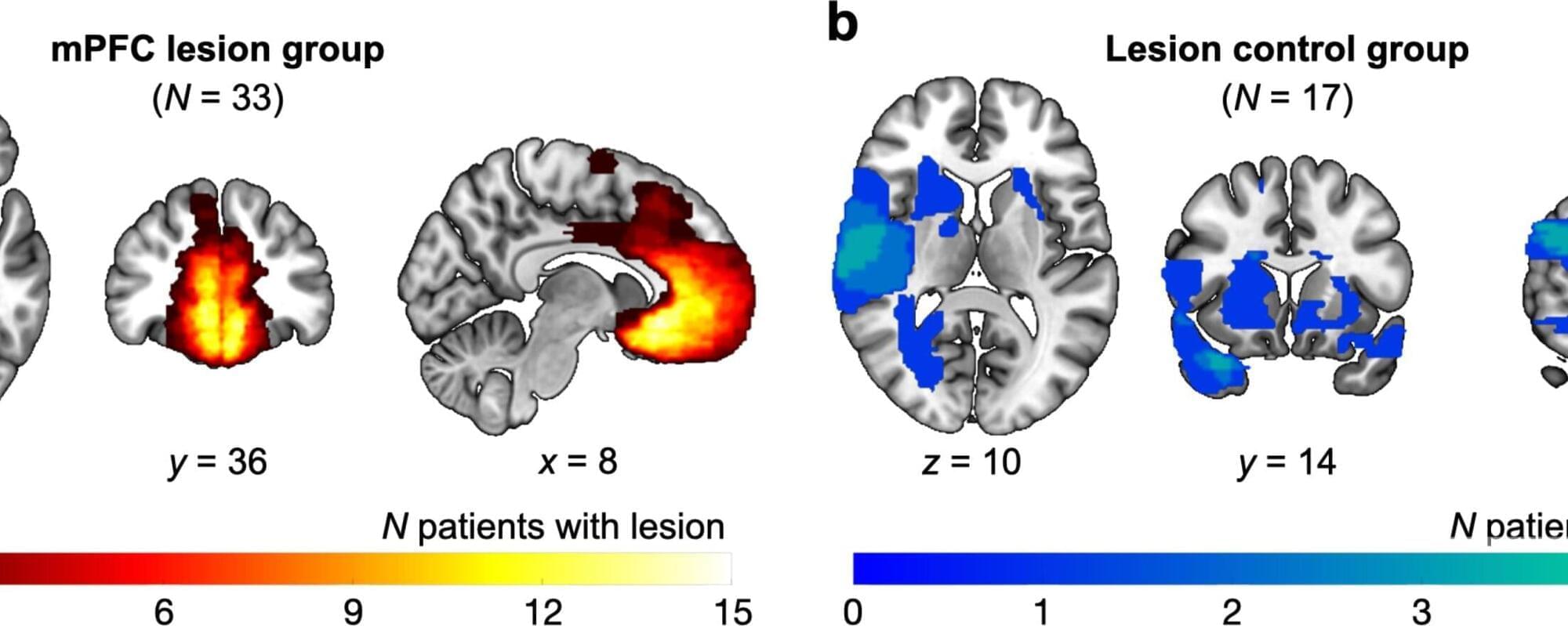

People who have damage to a specific part of their brains are more likely to be impulsive, and new research has found that damage also makes them more likely to be influenced by other people.

In a new study published in PLOS Biology, a research team found that damage to distinct parts of the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) was linked to being influenced by impulsive decision-making by others, while another region was causally linked with choosing a smaller reward earlier rather than waiting for a larger prize.

The team from the University of Birmingham, University of Oxford and Julius-Maximilians-University Würzburg worked with participants with brain damage to assess whether they were more likely to be influenced by other people’s preferences.

A study in China found that AI can spontaneously develop human-like understanding of natural objects without being trained to do so.

This is a reported phenomenon where if two copies of Claude talk to each other, they end up spiraling into rapturous discussion of spiritual bliss, Buddhism, and the nature of consciousness. From the system card: