A large-scale study challenges the long-held belief that musical training boosts the brain’s earliest stages of sound processing.

Research from Michigan State University finds that microbes play an important role in shaping early brain development, specifically in a key brain region that controls stress, social behavior, and vital body functions.

The study, published in Hormones and Behavior, used a mouse model to highlight how natural microbial exposure not only impacts brain structure immediately after birth but may even begin influencing development while still in the womb. A mouse model was chosen because mice share significant biological and behavioral similarities with humans and there are no other alternatives to study the role of microbes on brain development.

This work is of significance because modern obstetric practices, like peripartum antibiotic use and Cesarean delivery, disrupt maternal microbes. In the United States alone, 40% of women receive antibiotics around childbirth and one-third of all births occur via Cesarean section.

A lab-grown brain that mimics real brain function may offer breakthroughs in autism, schizophrenia, and mental health drug testing.

The idea of taking blood from the young to rejuvenate the elderly is getting an increasing amount of attention from scientists, and a new study has shown how some of the youthful properties of our skin can be restored with this kind of blood swap.

A special 3D human skin model was set up in the lab by researchers, who then tested the effects of young blood serum on the skin cells. By itself, the serum had no effect, but when bone marrow cells were added to the experiment, anti-aging signals were detected in the skin.

It appears that the young blood serum interacts with the bone marrow cells in specific ways to roll back time in skin cells. The study was led by scientists from Beiersdorf AG, a skin care company in Germany, who say their findings have huge potential in helping us understand anti-aging mechanisms.

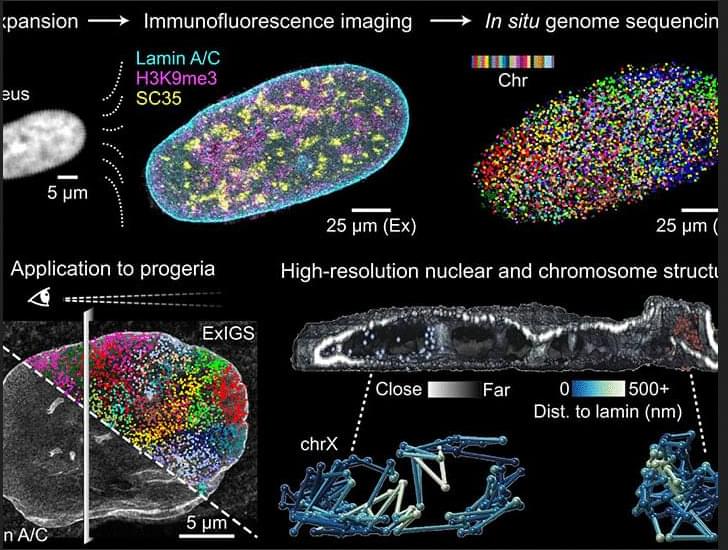

Great paper which combines expansion microscopy and in situ genome sequencing to map chromatin structure and selected protein targets in cellular nuclei. ExIGS was then used to explore how lamin protein and genome organization within nuclei changes during aging. #systemsbiology

Microscopy and genomics are used to characterize cell function, but approaches to connect the two types of information are lacking, particularly at subnuclear resolution. Here, we describe expansion in situ genome sequencing (ExIGS), a technology that enables sequencing of genomic DNA and super-resolution localization of nuclear proteins in single cells. Applying ExIGS to progeria-derived fibroblasts revealed that lamin abnormalities are linked to hotspots of aberrant chromatin regulation that may erode cell identity. Lamin was found to generally repress transcription, suggesting that variation in nuclear morphology may affect gene regulation across tissues and aged cells. These results demonstrate that ExIGS may serve as a generalizable platform with which to link nuclear abnormalities to gene regulation, offering insights into disease mechanisms.

A new specialized, radiation-hardened chip has been designed for CERN’s Large Hadron Collider (LHC) upgrade.

Engineers at Columbia University have developed this analog-to-digital converter (ADC) chip.

The custom-designed chips will be used in the ATLAS detector to measure up to 1.5 billion particle collisions per second.

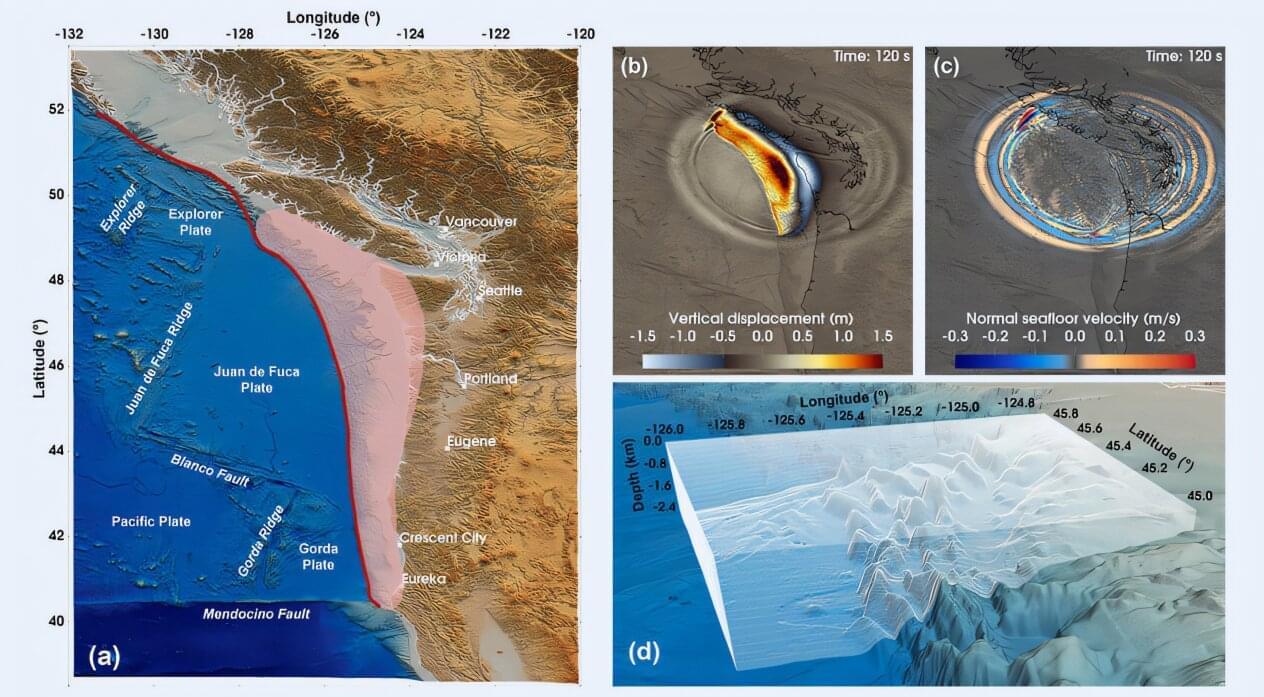

Scientists at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) have helped develop an advanced, real-time tsunami forecasting system—powered by El Capitan, the world’s fastest supercomputer—that could dramatically improve early warning capabilities for coastal communities near earthquake zones.

The exascale El Capitan, which has a theoretical peak performance of 2.79 quintillion calculations per second, was developed at the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA). As described in a preprint paper selected as a finalist for the 2025 ACM Gordon Bell Prize, researchers at LLNL harnessed the machine’s full computing power in a one-time, offline precomputation step, prior to the system’s transition to classified national-security work. The goal: to generate an immense library of physics-based simulations, linking earthquake-induced seafloor motion to resulting tsunami waves.

The paper is published on the arXiv preprint server.