Sam Harris discusses the coronavirus withAmesh Adalja.

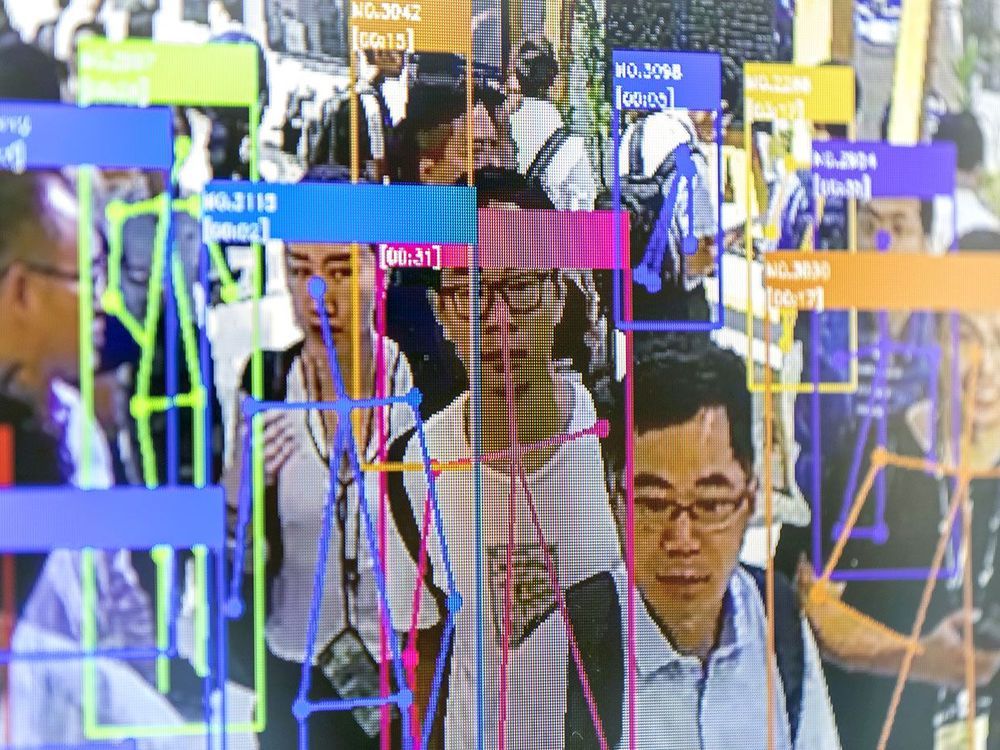

In this episode of the podcast, Sam Harris speaks with Amesh Adalja about the spreading coronavirus pandemic. They discuss the contagiousness of the virus and the severity of the resultant illness, the mortality rate and risk factors, vectors of transmission, how long coronavirus can live on surfaces, the importance of social distancing, possible anti-viral treatments, the timeline for a vaccine, the importance of pandemic preparedness, and other topics.

Amesh Adalja, MD, is an infectious disease specialist at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security. His work is focused on emerging infectious disease, pandemic preparedness, and biosecurity. Amesh has served on US government panels tasked with developing guidelines for the treatment of plague, botulism, and anthrax. He is an Associate Editor of the journal Health Security, co-editor of the volume Global Catastrophic Biological Risks, and a contributing author for the Handbook of Bioterrorism and Disaster Medicine. Amesh actively practices infectious disease, critical care, and emergency medicine in the Pittsburgh metropolitan area.

Website: www.trackingzebra.com

Twitter: @AmeshAA