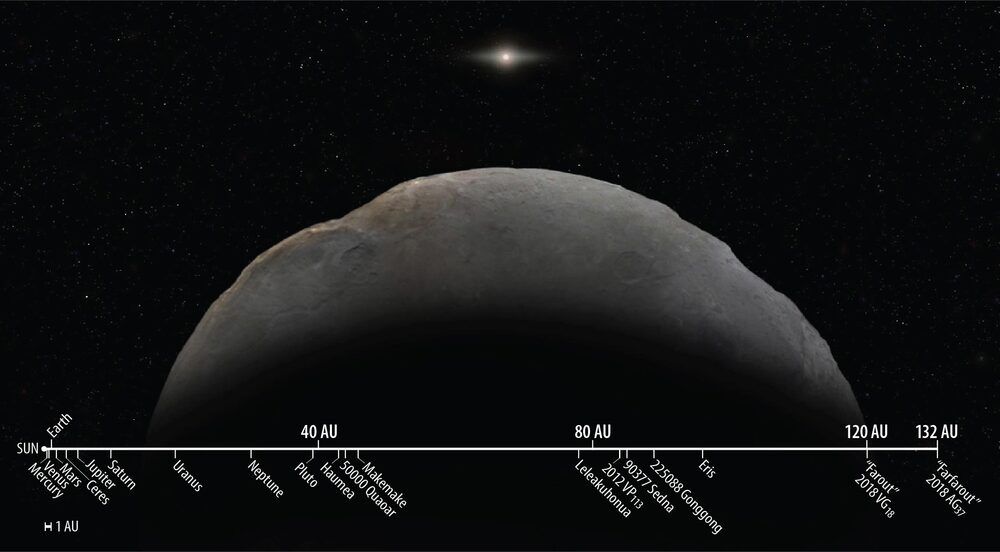

Pluto, the dwarf planet, resides around 3.1 billion miles from the Sun, while Farfarout is an incredible 12.2 billion miles from the Sun.

Category: space – Page 729

Perseverance: Countdown to Impact

About this partnership.

The Mars Perseverance Rover is in its final flight stages, heading for its historic rendezvous with the red planet. First up — a harrowing landing, scheduled for February 18th…Don’t miss it!

Learn more with Perseverance: Countdown to Impact now available on CuriosityStream.

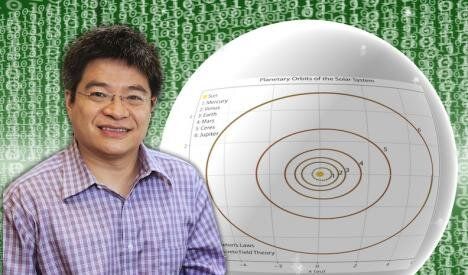

New Machine Learning Theory Raises Questions About the Very Nature of Science

A novel computer algorithm, or set of rules, that accurately predicts the orbits of planets in the solar system could be adapted to better predict and control the behavior of the plasma that fuels fusion facilities designed to harvest on Earth the fusion energy that powers the sun and stars.

The algorithm, devised by a scientist at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL), applies machine learning, the form of artificial intelligence (AI) that learns from experience, to develop the predictions. “Usually in physics, you make observations, create a theory based on those observations, and then use that theory to predict new observations,” said PPPL physicist Hong Qin, author of a paper detailing the concept in Scientific Reports. “What I’m doing is replacing this process with a type of black box that can produce accurate predictions without using a traditional theory or law.”

Qin (pronounced Chin) created a computer program into which he fed data from past observations of the orbits of Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, and the dwarf planet Ceres. This program, along with an additional program known as a “serving algorithm,” then made accurate predictions of the orbits of other planets in the solar system without using Newton’s laws of motion and gravitation. “Essentially, I bypassed all the fundamental ingredients of physics. I go directly from data to data,” Qin said. “There is no law of physics in the middle.”

“Farfarout” – Astronomers Confirm Solar System’s Most Distant Planetoid

A team, including an astronomer from the University of Hawaiʻi Institute for Astronomy (IfA), have confirmed a planetoid that is almost four times farther from the Sun than Pluto, making it the most distant object ever observed in our solar system. The planetoid, nicknamed “Farfarout,” was first det.

Elon Musk says Tesla’s electric van could have solar panels

Tesla CEO Elon Musk gave some details about the prospective electric van that the company could develop in the coming years. In an interview with Joe Rogan on the comedian’s podcast, the Joe Rogan Experience, Musk indicated that a van’s design would be more favorable to equip solar panels for stationary charging.

During Tesla’s Q4 2020 Earnings Call, TBC Capital Markets analyst Joseph Spak asked Musk about the possibility of developing an all-electric van. Vans have become a major player in the EV space since Rivian was contracted by e-commerce giant Amazon to build 100000 electric delivery vans. The vans have recently started testing in Southern California. Ford also developed an electric version of its Transit van.

The prospect of Tesla developing an electric van was confirmed by Musk during the Earnings Call.

Observations inspect radio emission from two magnetars

Using the Australia Telescope Compact Array (ATCA) and the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), astronomers have conducted a study of two magnetars known as PSR J1622−4950 and 1E 1547.0−5408. Results of this investigation, published February 4 on arXiv.org, provide important information about radio emission from these two sources.