Nuclear physicists make new, high-precision measurement of the layer of neutrons that encompass the lead nucleus, revealing new information about neutron stars.

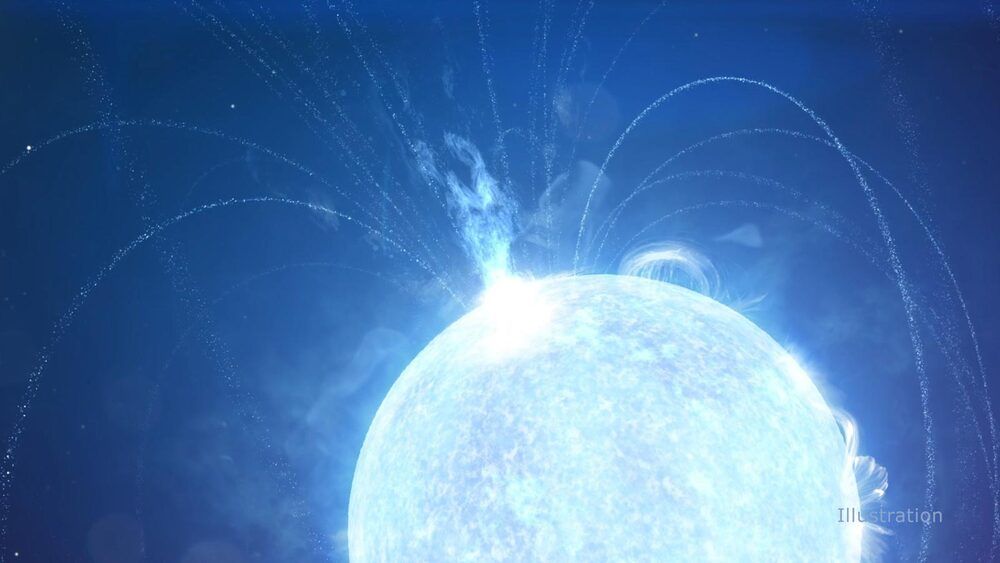

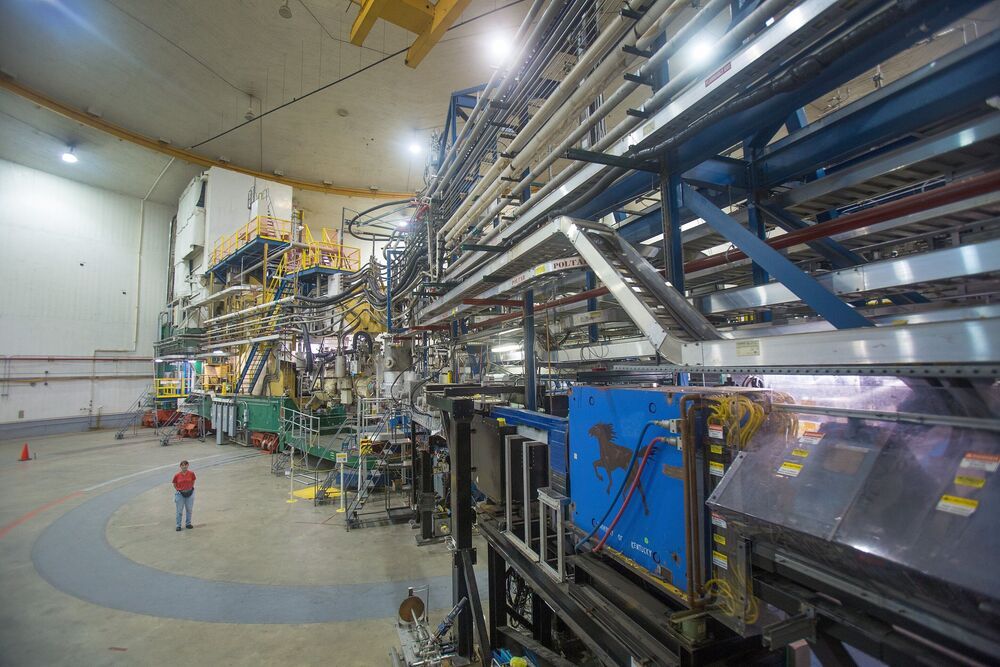

Nuclear physicists have made a new, highly accurate measurement of the thickness of the neutron “skin” that encompasses the lead nucleus in experiments conducted at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility and just published in Physical Review Letters. The result, which revealed a neutron skin thickness of .28 millionths of a nanometer, has important implications for the structure and size of neutron stars.

The protons and neutrons that form the nucleus at the heart of every atom in the universe help determine each atom’s identity and properties. Nuclear physicists are studying different nuclei to learn more about how these protons and neutrons act inside the nucleus. The Lead Radius Experiment collaboration, called PREx (after the chemical symbol for lead, Pb), is studying the fine details of how protons and neutrons are distributed in lead nuclei.