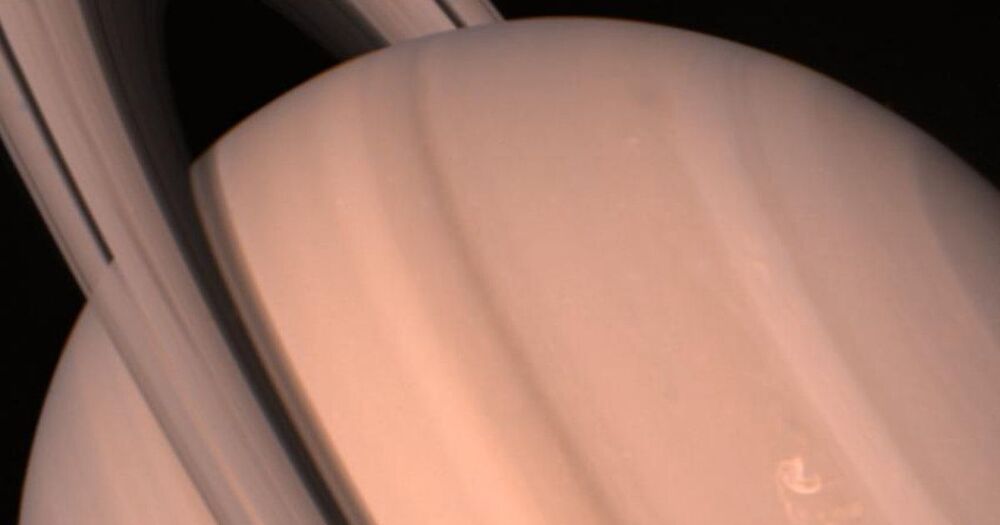

Astronomers have developed the most realistic model to date of planet formation in binary star systems.

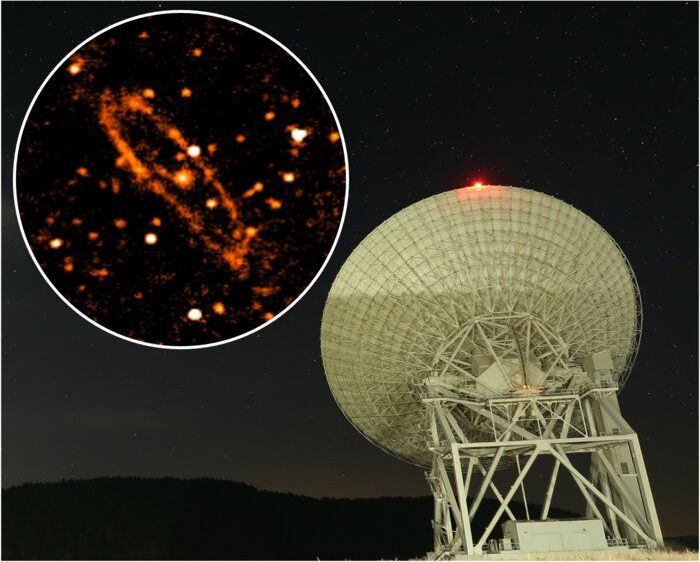

The researchers, from the University of Cambridge and the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics, have shown how exoplanets in binary star systems – such as the ‘Tatooine’ planets spotted by NASA

Established in 1958, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) is an independent agency of the United States Federal Government that succeeded the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA). It is responsible for the civilian space program, as well as aeronautics and aerospace research. It’s vision is “To discover and expand knowledge for the benefit of humanity.”