Category: space – Page 667

Our NASA’s Curiosity Mars Rover has driven over 16 miles since landing on the Red Planet in 2012

Now, the robot geologist reached an exciting area with mountain layers that may reveal how the ancient environment within Gale Crater dried up over time. More: https://go.nasa.gov/2W48e0U

Star Trek has served as inspiration to generations of scientists, engineers and sci-fi fans around the world

Join Rod Roddenberry, Gene Roddenberry’s son and Roddenberry Entertainment CEO, George Takei, actor and activist, Administrator Bill Nelson and some of NASA’s best and brightest as they honor Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry’s 100th birthday with a conversation about diversity and inspiration. NASA panelists include: Hortense Diggs, Director of the Office of Communication and Public Engagement at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, Tracy Drain, Europa Clipper Flight Systems Engineer, astronaut Jonny Kim, and Swati Mohan, Mars2020Guidance and Controls Operations Lead.

Producer/Editor: Lacey Young

Would you like to live on Mars for a year?

Learn more about what it’s like living in space: http://ow.ly/yHiO50FO9qv

New observations challenge popular radio burst model

Strange behavior caught by two radio observatories may send theorists back to the drawing board.

Fourteen years ago, the first fast radio burst (FRB) was discovered. By now, many hundreds of these energetic, millisecond-duration bursts from deep space have been detected (most of them by the CHIME radio observatory in British Columbia, Canada), but astronomers still struggle to explain their enigmatic properties. A new publication in this week’s Nature “adds a new piece to the puzzle,” says Victoria Kaspi (McGill University, Canada). “In this field of research, surprising twists are almost as common as new results.”

Most astronomers agree that FRBs are probably explosions on the surfaces of highly magnetized neutron stars (so-called magnetars). But it’s unclear why most FRBs appear to be one-off events, while others flare repeatedly. In some cases, these repeating bursts show signs of periodicity, and scientists had come up with an attractive model to explain this behavior, involving stellar winds in binary systems.

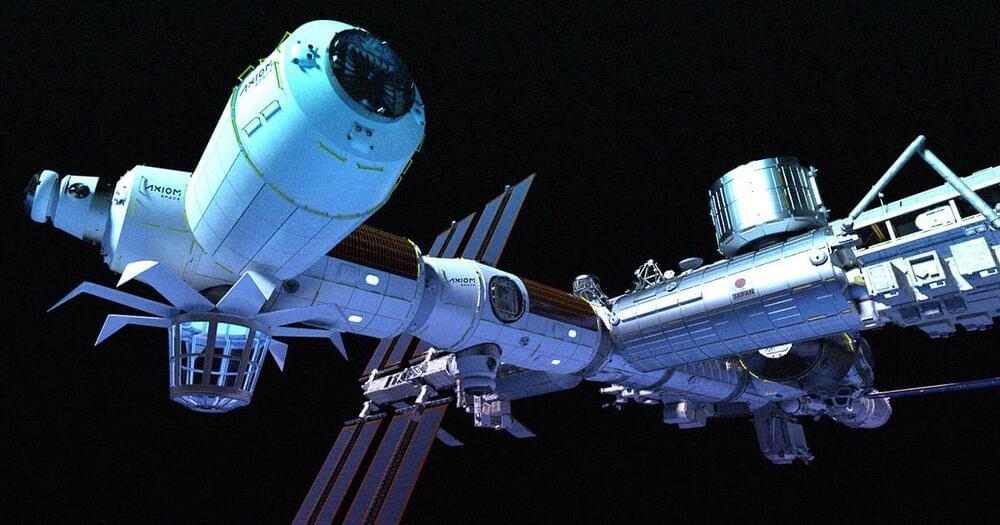

Someone Is Secretly Working on “Privately Owned” Space Station

Collins Aerospace, a subsidiary of military and aerospace contractor Raytheon Technologies, is working on environmental control and life support technologies for a “privately owned and operated low Earth orbit outpost,” according to SpaceNews.

There’s plenty of money being poured into developing a commercial presence in space right now. The small firm was awarded a $2.6 million contract by a mysterious unnamed customer — a sign, in spite of its opacity, that the race to commercial orbit is heating up.

Google Cloud launches Vertex AI, a new managed machine learning platform

At Google I/O today Google Cloud announced Vertex AI, a new managed machine learning platform that is meant to make it easier for developers to deploy and maintain their AI models. It’s a bit of an odd announcement at I/O, which tends to focus on mobile and web developers and doesn’t traditionally feature a lot of Google Cloud news, but the fact that Google decided to announce Vertex today goes to show how important it thinks this new service is for a wide range of developers.

The launch of Vertex is the result of quite a bit of introspection by the Google Cloud team. “Machine learning in the enterprise is in crisis, in my view,” Craig Wiley, the director of product management for Google Cloud’s AI Platform, told me. “As someone who has worked in that space for a number of years, if you look at the Harvard Business Review or analyst reviews, or what have you — every single one of them comes out saying that the vast majority of companies are either investing or are interested in investing in machine learning and are not getting value from it. That has to change. It has to change.”