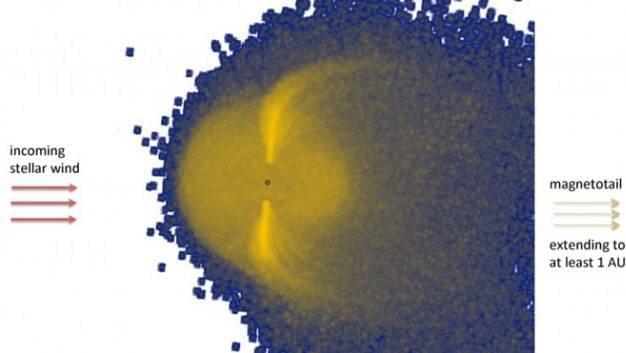

An international scientific group with outstanding Valencian participation has managed to measure for the first time oscillations in the brightness of a magnetar during its most violent moments. In just a 10th of a second, the magnetar released energy equivalent to that produced by the sun in 100,000 years. The observation was carried out without human intervention, thanks to an artificial intelligence system developed at the Image Processing Laboratory (IPL) of the University of Valencia.

Among neutron stars, objects that can contain a half-million times the mass of the Earth in a diameter of about 20 kilometers, are magnetars, a small group with the most intense magnetic fields known. These objects, of which only 30 are known, suffer violent eruptions that are still little known due to their unexpected nature and their duration of barely 10ths of a second. Detecting them is a challenge for science and technology.

Over the past 20 years, scientists have wondered if there are high frequency oscillations in the magnetars. The team recently published their study of the eruption of a magnetar in the journal Nature. They measured oscillations in the brightness of the magnetar during its most violent moments. These episodes are a crucial component in understanding giant magnetar eruptions. The work was conducted by six researchers from the University of Valencia and Spanish collaborators.