Using the TUBITAK National Observatory and ESA’s Gaia satellite, astronomers from the Istanbul University in Turkey and elsewhere have conducted comprehensive observations of two open clusters, namely: Czernik 41 and NGC 1342. Results of the observational campaign, published July 7 on the arXiv preprint server, deliver important insights into the properties of these clusters.

Open clusters (OCs) are groups of stars formed from the same giant molecular cloud and loosely gravitationally bound to each other. Astronomers are interested in inspecting OCs in detail as such studies could be crucial for improving our understanding of the formation and evolution of our galaxy.

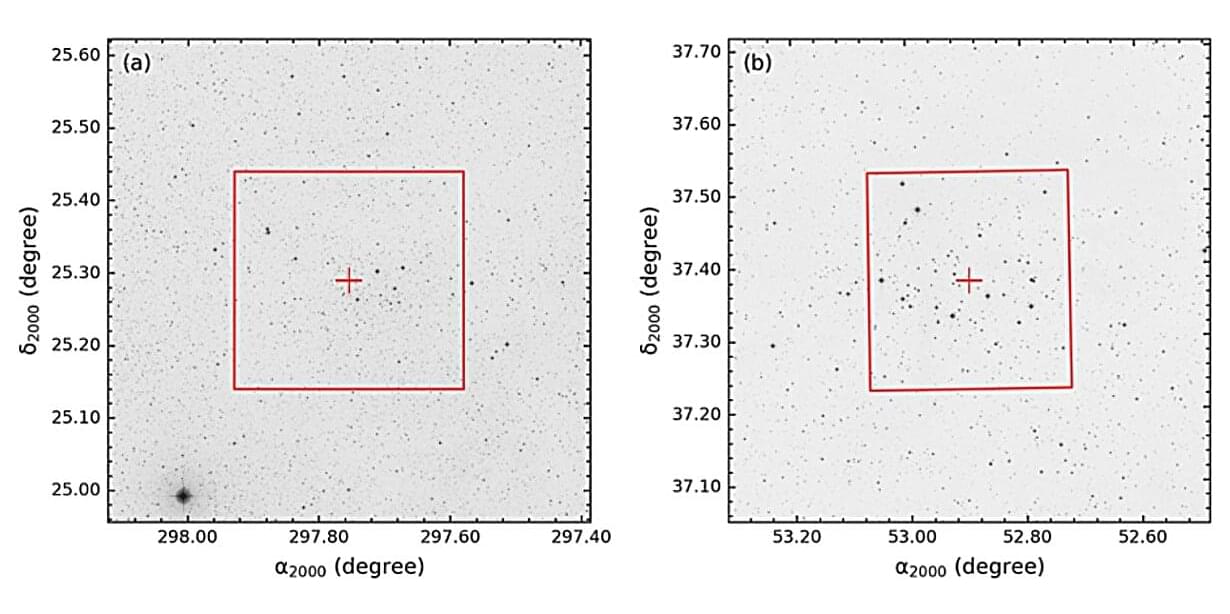

That is why a group of researchers led by Istanbul University’s Burçin Tanık Öztürk decided to take a closer look at two well-known OCs—Czernik 41, discovered in 1966, and NGC 1,342, dubbed the Stingray Cluster, which was identified by William Herschel in 1799. For this purpose, they employed the T100 telescope at the TUBITAK National Observatory in Turkey and analyzed the data from the Gaia satellite.