At a time when astronomers around the world are reveling in new views of the distant cosmos, an experiment on the International Space Station has given Cornell researchers fresh insight into something a little closer to home: water.

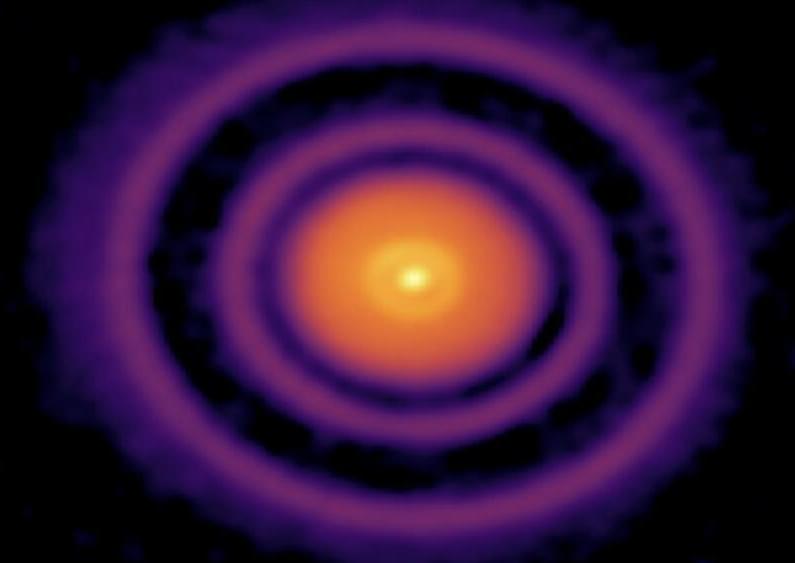

Asteroid Bennu was in the news recently for an astonishing discovery. NASA scientists revealed that the asteroid has a surface that appears similar to plastic balls. The discovery dates back to October 2020, when NASA successfully collected a sample from the asteroid.

During the sampling event, the sampling head of the OSIRIS-REx (Origins, Spectral Interpretation, Resource Identification, Security-Regolith Explorer) spacecraft had sunk by 1.6 feet (0.5 meters) into the surface of the asteroid. The space agency found that Bennu’s exterior is made of loosely packed particles that are haphazardly packed together. The spacecraft would have sunk right into the asteroid if it hadn’t fired its thruster to back away after collecting dust and rocks.

The new method could be the key to getting oxygen to Mars and beyond.

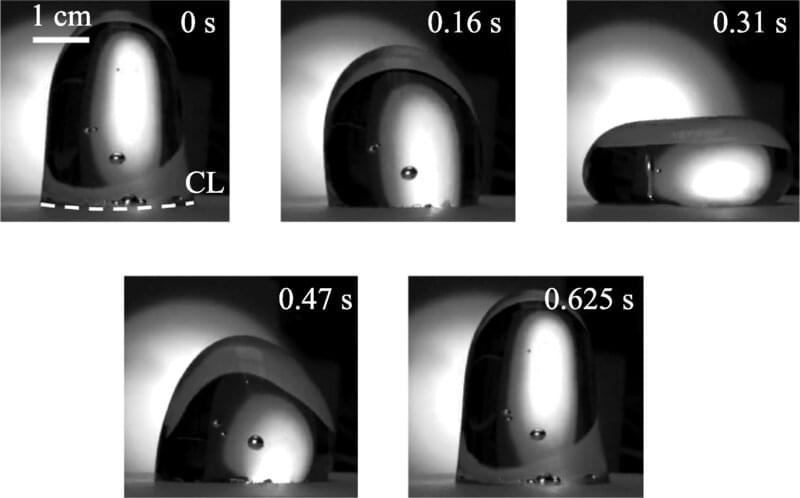

The study was conducted in a special drop tower facility that simulates microgravity conditions. The research proved magnets were effective at producing oxygen. The new method removes gas bubbles from liquids. Producing enough oxygen for astronauts in space is a complicated affair that is only set to become more difficult as we travel to Mars and beyond.

Now, researchers have invented a new way to make oxygen for astronauts using magnets, according to a University of Warwick statement.

Getting oxygen in space using magnets On the International Space Station, oxygen is generated using an electrolytic cell that splits water into hydrogen and oxygen, but then you have to get those gasses out of the system.

A relatively recent analysis from a researcher at NASA Ames concluded that adapting the same architecture on a trip to Mars would have such significant mass and reliability penalties that it wouldn’t make any sense to use, said lead author Álvaro Romero-Calvo, a recent Ph.D. graduate from the University of Colorado Boulder.

NASA currently uses centrifuges to get oxygen in space but those machines are large and require significant mass, power, and maintenance. The new research has conducted practical experiments showcasing magnets could achieve the same results much more practically.

Full Story:

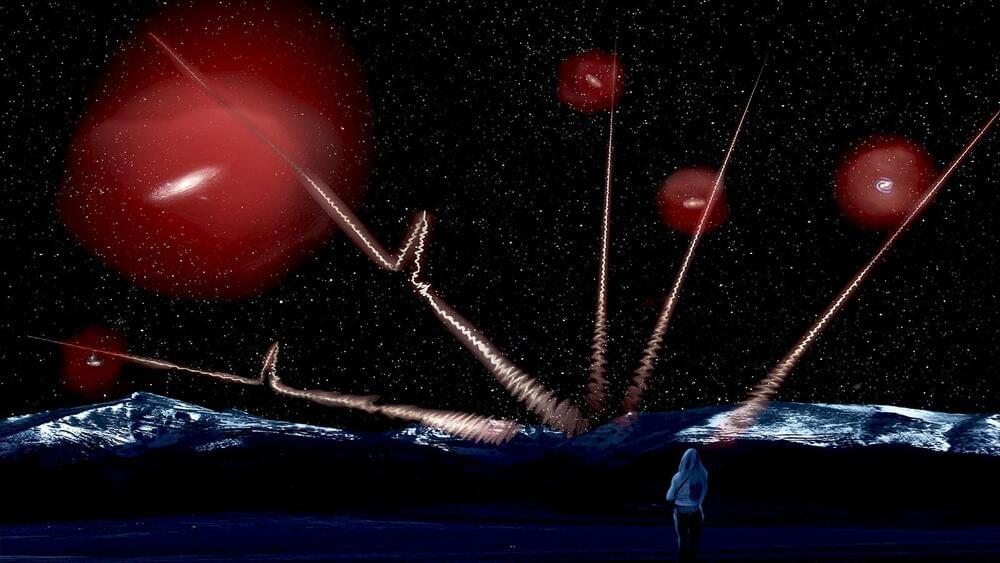

Powerful cosmic radio pulses originating deep in the universe can be used to study hidden pools of gas cocooning nearby galaxies, according to a new study that was published last month in the journal Nature Astronomy.

So-called fast radio bursts, or FRBs, are pulses of radio waves that typically originate millions to billions of light-years away. (Radio waves are electromagnetic radiation like the light we see with our eyes but have longer wavelengths and lower frequencies). The first FRB was discovered in 2007, and since then, hundreds more have been detected. In 2020, Caltech’s STARE2 instrument (Survey for Transient Astronomical Radio Emission 2) and Canada’s CHIME (Canadian Hydrogen Intensity Mapping Experiment) detected a massive FRB that went off in our own Milky Way galaxy. Those earlier findings helped confirm the theory that the energetic events most likely originate from dead, magnetized stars called magnetars.

As more and more FRBs roll in, scientists are now investigating how they can be used to study the gas that lies between us and the bursts. Specifically, they would like to use the FRBs to probe halos of diffuse gas that surround galaxies. As the radio pulses travel toward Earth, the gas enveloping the galaxies is expected to slow the waves down and disperse the radio frequencies. In the new study, the research team looked at a sample of 474 distant FRBs detected by CHIME, which has discovered the most FRBs to date. They showed that the subset of two dozen FRBs that passed through galactic halos were indeed slowed down more than non-intersecting FRBs.