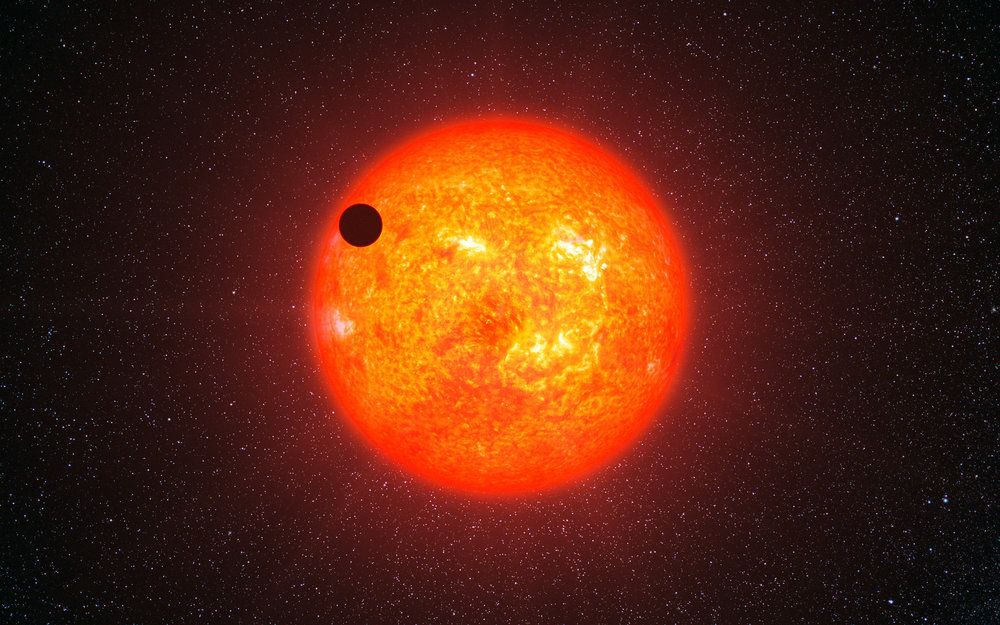

The study of exoplanets has advanced by leaps and bounds in the past few decades. Between ground-based observatories and spacecraft like the Kepler mission, a total of 3,726 exoplanets have been confirmed in 2,792 systems, with 622 systems having more than one planet (as of Jan. 1st, 2018). And in the coming years, scientists expect that many more discoveries will be possible thanks to the deployment of next-generation missions.

These include NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and several next-generation ground based observatories. With their advanced instruments, these and other observatories are not only expected to find many more exoplanets, but to reveal new and fascinating things about them. For instance, a recent study from Columbia University indicated that it will be possible, using the Transit Method, to study surface elevations on exoplanets.