An unusual SpaceX launch will carry several startups’ satellites, some of which will jockey to provide dirt-cheap internet for earthbound IoT sensors.

Really?

Ethiopia has announced its intention to launch its first satellite during 2019. According to the Ethiopian Space Science and Technology Institute (ESSTI) at the Addis Ababa University, the satellite is expected to be launched from China during September 2019.

The initial plans to launch the satellite were announced in 2016 at the same time the Ethiopian Council of Ministers approved the establishment of ESSTI.

Location data beamed from GPS satellites are used by smartphones, car navigation systems, the microchip in your dog’s neck and guided missiles — and all those satellites are controlled by the U.S. Air Force. That makes the Chinese government uncomfortable, so it’s developing an alternative that a U.S. security analyst calls one of the largest space programs the country has undertaken.

The Beidou Navigation System will be accessible worldwide by 2020.

Satellites and rockets are getting smaller. Why not rovers, too?

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. (AP) — A pair of tiny experimental satellites trailing NASA’s InSight spacecraft all the way to Mars face their biggest test yet. Their mission: Broadcast immediate news, good or bad, of InSight’s plunge through the Martian atmosphere on Monday. Named WALL-E and EVE after the main characters in the 2008 animated movie, the twin CubeSats will pass within a few thousand miles (kilometers) of Mars as the lander attempts its dicey touchdown. If these pipsqueaks manage to relay InSight’s radio signals to ground controllers nearly 100 million miles (160 million kilometers) away, we’ll know within minutes whether the spacecraft landed safely.

Every action creates an equal and opposite reaction. It’s perhaps the best known law of physics, and Guido Fetta thinks he’s found a way around it.

According to classical physics, in order for something—like a spaceship—to move, conservation of momentum requires that it has to exert a force on something else. A person in roller skates, for example, pushes off against a wall; a rocket accelerates upward by propelling high-velocity combusted fuel downward. In practice, this means that space vessels like satellites and space stations have to carry up to half their weight in propellant just to stay in orbit. That bulks up their cost and reduces their useful lifetime.

Imagine an airport where thousands of planes, empty of fuel, are left abandoned on the tarmac. That is what has been happening for decades with satellites that circle the Earth.

When satellites run out of fuel, they can no longer maintain their precise orbit, rendering them useless even if their hardware is still intact.

“It’s literally throwing away hundreds of millions of dollars,” Al Tadros, vice president of space infrastructure and civil Space at a company called SSL, said this month at a meeting in the US capital of key players in the emerging field of on-orbit servicing, or repairing satellites while they are in space.

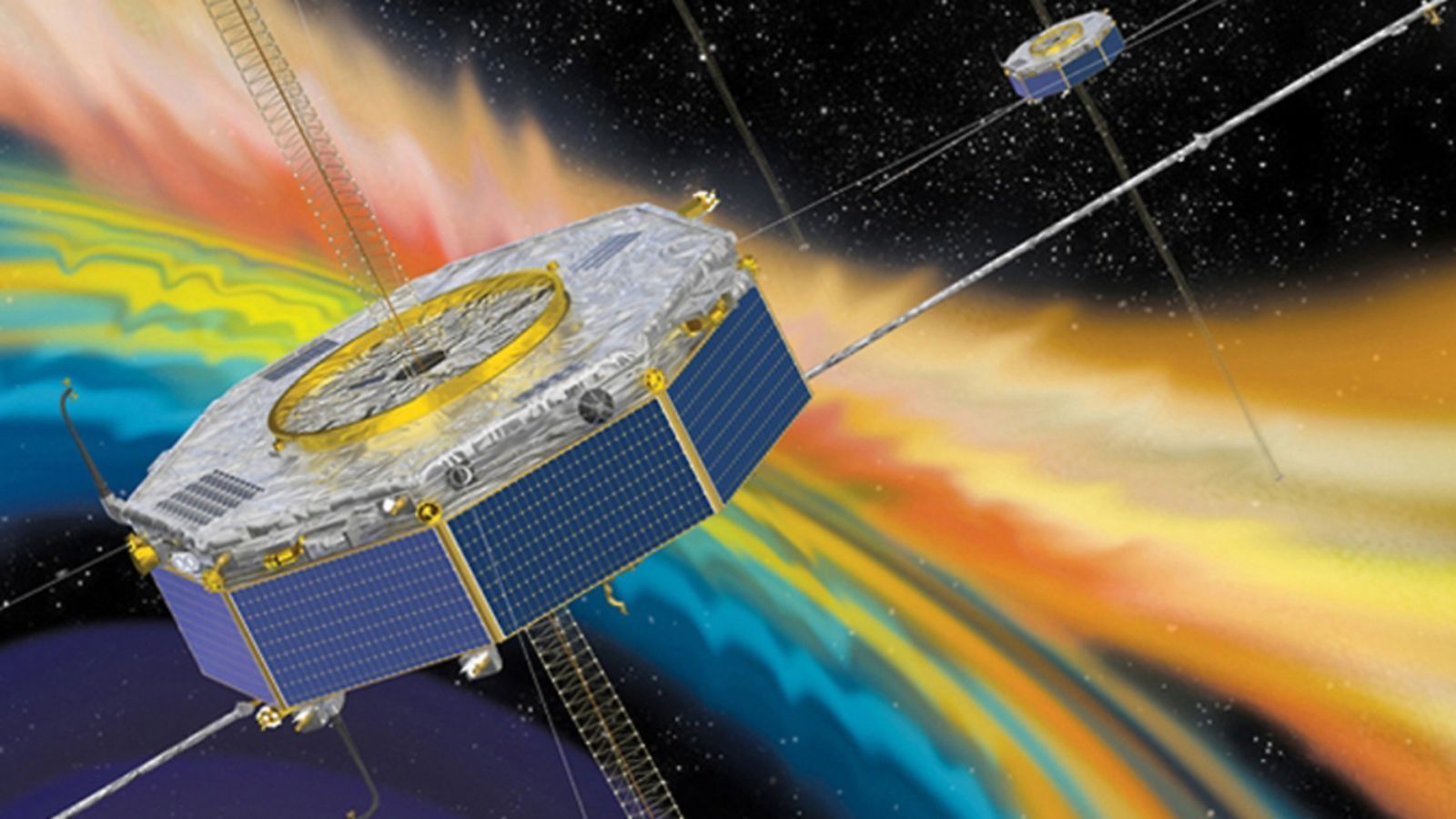

Magnetic fields around the Earth release strong bursts of energy, accelerating particles and feeding the auroras that glow in the polar skies. On July 11, 2017, four NASA spacecrafts were there to watch one of these explosions happen.

The process that produces these bursts is called magnetic reconnection, in which different plasmas and their associated magnetic fields interact, releasing energy. The Magnetospehric Multiscale Mission (MMS) satellites launched in 2015 to study the places where this reconnection process occurs. This newly released research shows for the first time that the mission encountered one of these reconnection sites in the night side of the Earth’s magnetic field, which extends behind the planet as a long “magnetotail.”

SpaceX today received US approval to deploy 7,518 broadband satellites, in addition to the 4,425 satellites that were approved eight months ago.

The Federal Communications Commission voted to let SpaceX launch 4,425 low-Earth orbit satellites in March of this year. SpaceX separately sought approval for 7,518 satellites operating even closer to the ground, saying that these will boost capacity and reduce latency in heavily populated areas. That amounts to 11,943 satellites in total for SpaceX’s Starlink broadband service.

SpaceX “proposes to add a very-low Earth orbit (VLEO) NGSO [non-geostationary satellite orbit] constellation, consisting of 7,518 satellites operating at altitudes from 335km to 346km,” the FCC said in the draft of the order that it approved unanimously today. The newly approved satellites would use frequencies between 37.5 and 42GHz for space-to-Earth transmissions and frequencies between 47.2 and 51.4GHz for Earth-to-space transmissions, the FCC said.