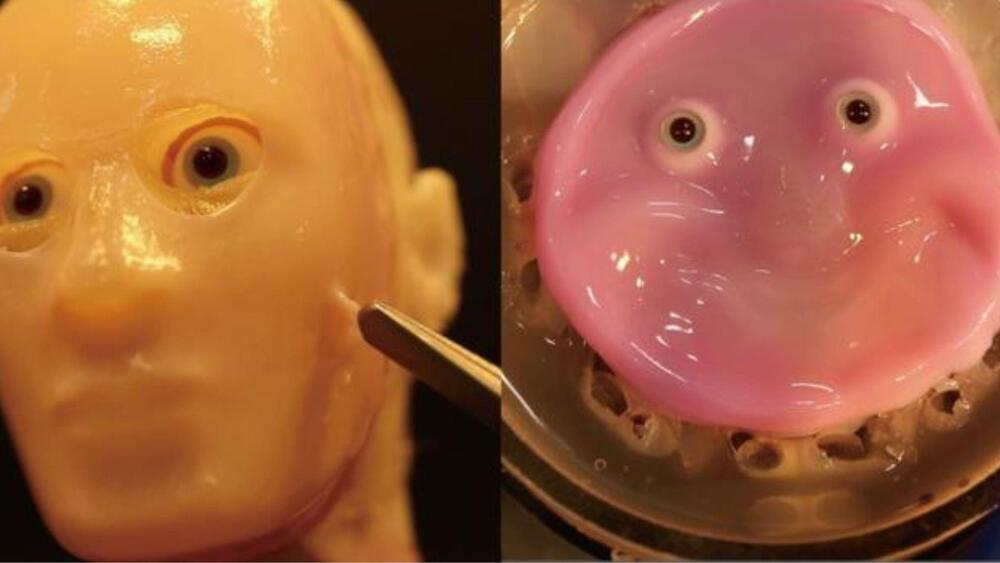

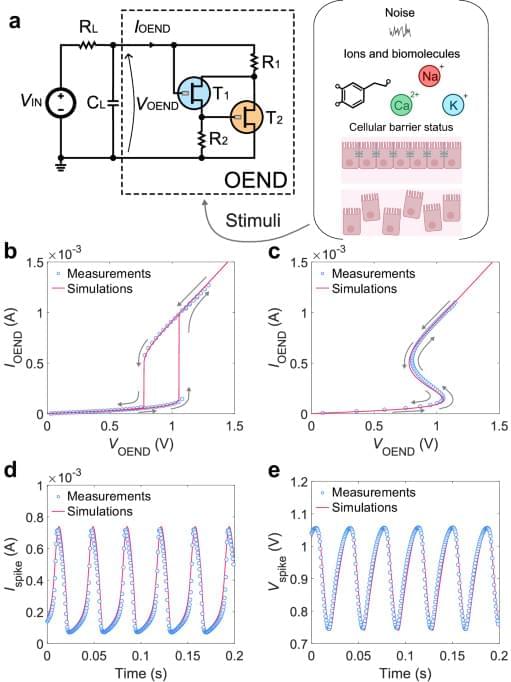

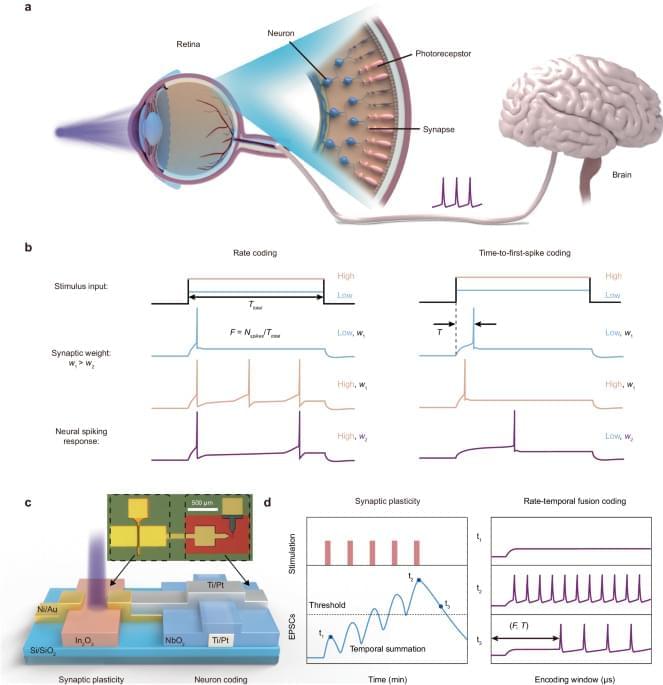

Organic electrochemical artificial neurons (OANs) are the latest entry of building blocks, with a few different approaches for circuit realization. OANs possess the remarkable capability to realistically mimic biological phenomena by responding to key biological information carriers, including alkaline ions, noise in the electrolyte, and biological conditions. An organic artificial neuron with a cascade-like topology made of OECT inverters has shown basic (regular) firing behavior and firing frequency that is responsive to the concentration of ionic species (Na+, K+) of the host liquid electrolyte33. An organic artificial neuron consisting of a non-linear building block that displays S-shape negative differential resistance (S-NDR) has also been recently demonstrated34. Due to the realization of the non-linear circuit theory with OECTs and the sharp threshold for oscillations, this artificial neuron displays biorealistic firing properties and neuronal excitability that can be found in the biological domain such as input voltage-induced regular and irregular firing, ion and neurotransmitter-induced excitability and ion-specific oscillations. Biohybrid devices comprising artificial neurons and biological membranes have also shown to operate synergistically, with membrane impedance state modulating the firing properties of the biohybrid in situ. More recently, a circuit leveraging the non-linear properties of antiambipolar OMIECs, which exhibit negative differential transconductance, has been realized35. These neurons show biorealistic properties such as various firing modes and responsivity to biologically relevant ions and neurotransmitters. With this neuron, ex-situ electrical stimulation has been shown in a living biological model. Therefore, the class of OANs perfectly complements the broad range of features already demonstrated by solid-state spiking circuits (Supplementary Table 1), offering opportunities for both hybrid interfacing between these technologies and new developments in neuromorphic bioelectronics.

Despite the promising recent realizations of organic artificial neurons, all approaches still remain in the qualitative demonstration domain and a rigorous investigation of circuit operation is still missing. Indeed, quantitative models exist only for inorganic, solid-state artificial neurons without the inclusion of physical soft-matter parameters and the biological wetware (i.e., aqueous electrolytes, alkaline ions, biomembranes)36,37. This gap in knowledge significantly impedes the simulation of larger-scale functional circuits, and therefore the design and development of integrated organic neuromorphic electronics, biohybrids, OAN-based neural networks, and intelligent bioelectronics.

In this work, we unravel the operation of organic artificial neurons that display non-linear phenomena such as S-shape negative differential resistance (S-NDR). By combining experiments, numerical simulations of non-linear iontronic circuits, and newly developed analytical expressions, we investigate, reproduce, rationalize, and design the wide biorealistic repertoire of organic electrochemical artificial neurons including their firing properties, neuronal excitability, wetware operation, and biohybrid formation. The OAN operation is efficiently rationalized to include how neuronal dynamics are probed by biochemical stimuli in the electrolyte medium. The OAN behavior is also extended on the biohybrid formation, with a solid rationale of the in situ interaction of OANs with biomembranes. Non-linear simulations of OANs are rooted in a physics-based framework, considering ion type, ion concentration, organic mixed ionic–electronic parameters, and biomembrane properties. The derived analytical expressions establish a direct link between OAN spiking features and its physical parameters and therefore provide a mapping between neuronal behavior and materials/device parameters. The proposed approach open opportunities for the design and engineering of advanced biorealistic OAN systems, establishing essential knowledge and tools for the development of neuromorphic bioelectronics, in-liquid neural networks, biohybrids, and biorobotics.