This could be the last decade that cosmologists debate how fast the universe is expanding.

Wormholes — yawning gateways that could theoretically connect distant points in space-time — are usually illustrated as gaping gravity wells linked by a narrow tunnel.

But their precise shape has been unknown.

Now, however, a physicist in Russia has devised a method to measure the shape of symmetric wormholes — even though they have not been proven to exist — based on the way the objects may affect light and gravity. [8 Ways You Can See Einstein’s Theory of Relativity in Real Life].

Physics tells us that a hammer and a feather, dropped in a vacuum, will fall at the same rate – as famously demonstrated by an Apollo 15 astronaut on the Moon. Now, CERN scientists are preparing to put a spooky new spin on that experiment, by dropping antimatter in a vacuum chamber to see if gravity affects it the same way it does matter – or if antimatter falls upwards instead.

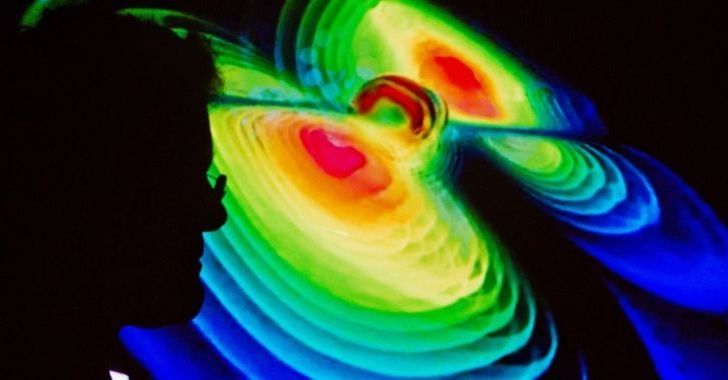

The news we had finally found ripples in space-time reverberated around the world in 2015. Now it seems they might have been an illusion.

LIGO’s detectorsEnrico Sacchetti

THERE was never much doubt that we would observe gravitational waves sooner or later. This rhythmic squeezing and stretching of space and time is a natural consequence of one of science’s most well-established theories, Einstein’s general relativity. So when we built a machine capable of observing the waves, it seemed that it would be only a matter of time before a detection.

“The first direct detection of gravitational waves was announced on February 11, 2016, spawned headlines around the world, snagged the 2017 Nobel Prize in Physics, and officially launched a new era of so-called “multi-messenger” astronomy. But a team of physicists at the Niels Bohr Institute in Copenhagen, Denmark, is calling that detection into question…”

“Andrew Jackson and his group have been saying for the past few years that LIGO’s detections are not real,” says LIGO Executive Director David Reitze of Caltech. “Their analysis has been looked at by many people who have all concluded there is absolutely no validity to their claims.” Reitze characterized the New Scientist article as “very biased and sensational.”

“Nothing they’ve done gives us any reason to doubt our results.”

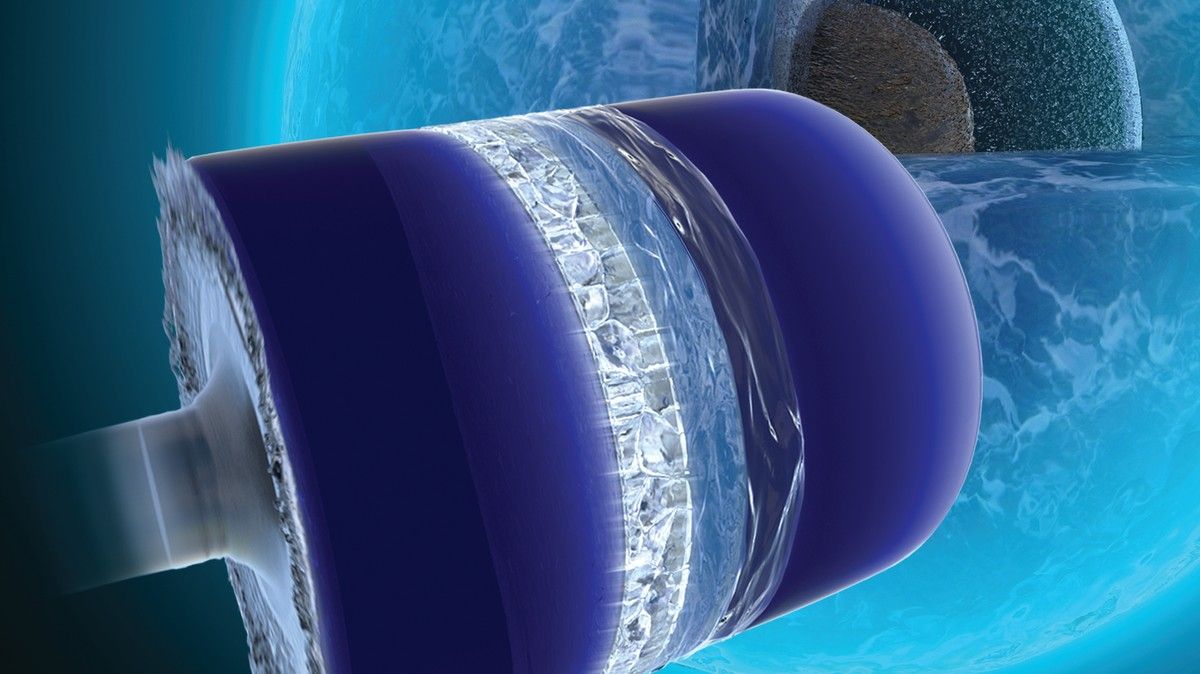

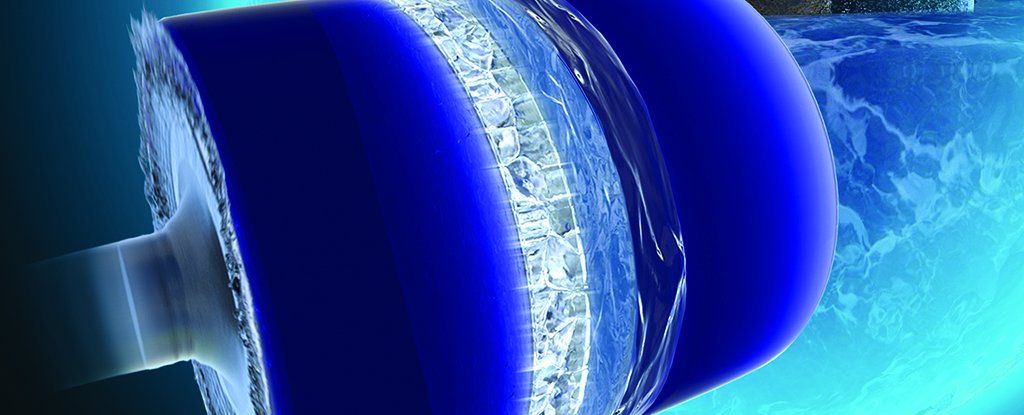

New research into a very weird type of ice known as Ice VII has revealed how it can form at speeds over 1,000 miles per hour (1,610 kilometres per hour), and how it might be able to spread across yet-to-be-explored alien worlds.

This ice type was only discovered occurring naturally in March, trapped inside diamonds deep underground, and this latest study looks in detail at how exactly it takes shape – apparently in a way that’s completely different to how water usually freezes into ice.

Based on a mathematical model devised by researchers from the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California, there’s a certain pressure threshold across which Ice VII will spread with lightning speed. This process of near-instantaneous transformation is known as homogeneous nucleation.