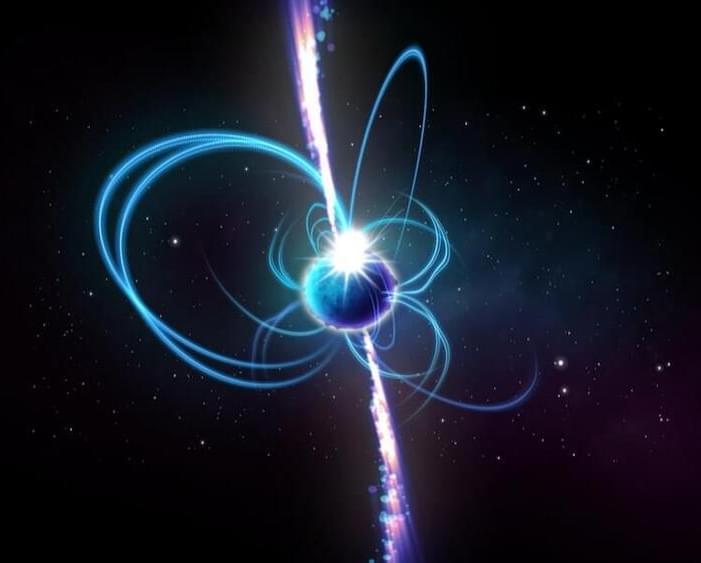

Imagine if we could use strong electromagnetic fields to manipulate the local properties of spacetime—this could have important ramifications in terms of science and engineering.

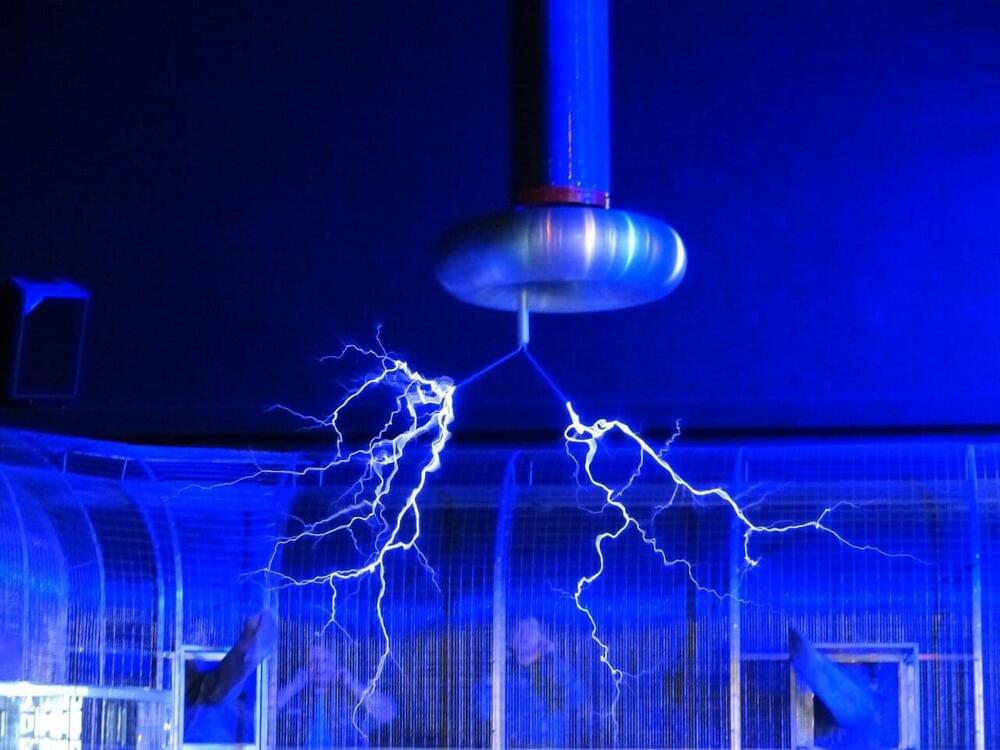

Electromagnetism has always been a subtle phenomenon. In the 19th century, scholars thought that electromagnetic waves must propagate in some sort of elusive medium, which was called aether. Later, the aether hypothesis was abandoned, and to this day, the classical theory of electromagnetism does not provide us with a clear answer to the question in which medium electric and magnetic fields propagate in vacuum. On the other hand, the theory of gravitation is rather well understood. General relativity explains that energy and mass tell the spacetime how to curve and spacetime tells masses how to move. Many eminent mathematical physicists have tried to understand electromagnetism directly as a consequence of general relativity. The brilliant mathematician Hermann Weyl had especially interesting theories in this regard. The Serbian inventor Nikola Tesla thought that electromagnetism contains essentially everything in our universe.