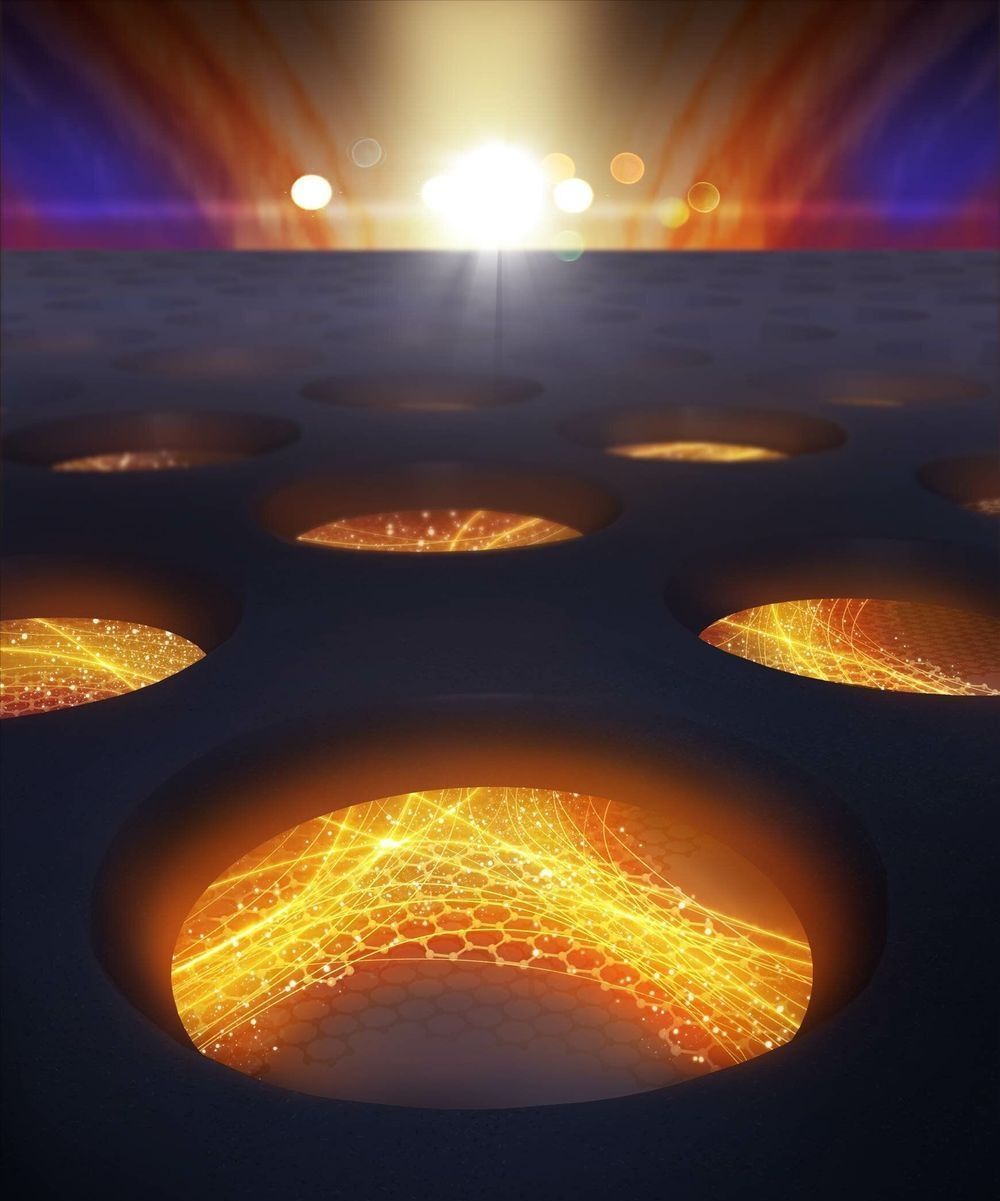

For 15 years, scientists have tried to exploit the “miracle material” graphene to produce nanoscale electronics. On paper, graphene should be great for just that: it is ultra-thin—only one atom thick and therefore two-dimensional, it is excellent for conducting electrical current, and holds great promise for future forms of electronics that are faster and more energy efficient. In addition, graphene consists of carbon atoms – of which we have an unlimited supply.

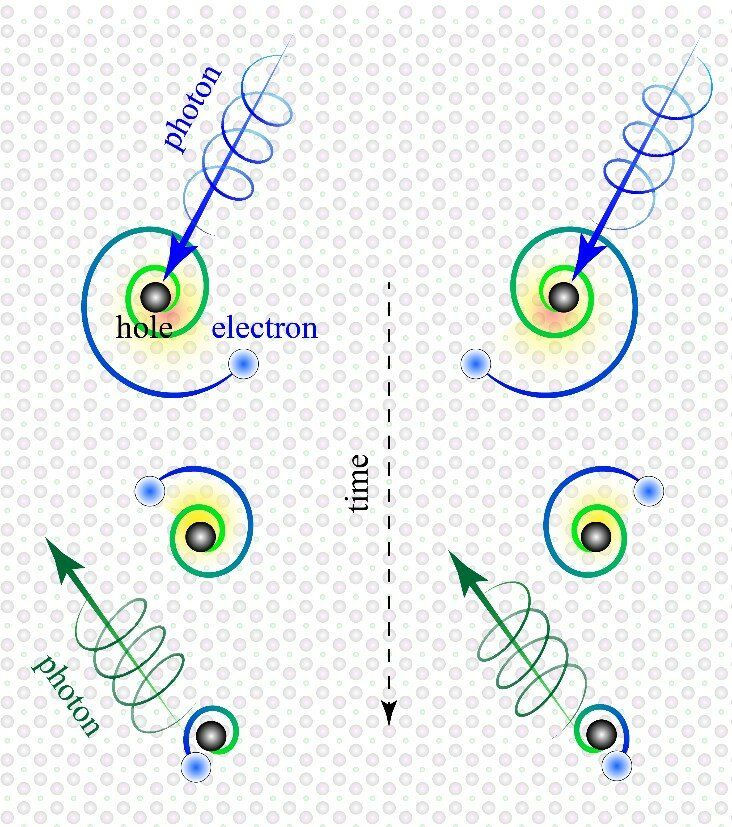

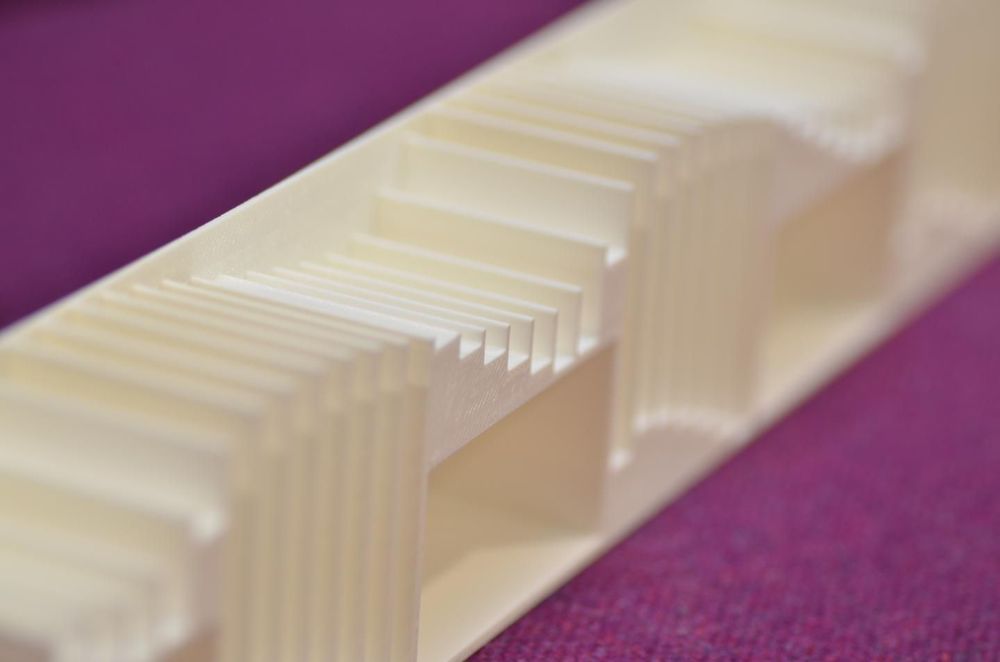

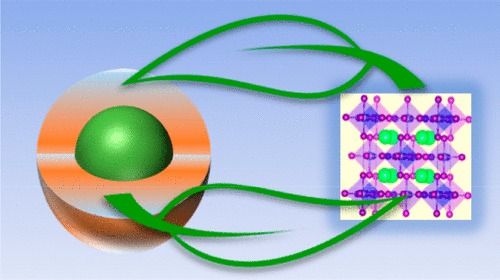

In theory, graphene can be altered to perform many different tasks within e.g. electronics, photonics or sensors simply by cutting tiny patterns in it, as this fundamentally alters its quantum properties. One “simple” task, which has turned out to be surprisingly difficult, is to induce a band gap—which is crucial for making transistors and optoelectronic devices. However, since graphene is only an atom thick all of the atoms are important and even tiny irregularities in the pattern can destroy its properties.

“Graphene is a fantastic material, which I think will play a crucial role in making new nanoscale electronics. The problem is that it is extremely difficult to engineer the electrical properties,” says Peter Bøggild, professor atDTU Physics.