On the electromagnetic spectrum, terahertz light is located between infrared radiation and microwaves. It holds enormous potential for tomorrow’s technologies: Among other things, it might succeed 5G by enabling extremely fast mobile communications connections and wireless networks. The bottleneck in the transition from gigahertz to terahertz frequencies has been caused by insufficiently efficient sources and converters. A German-Spanish research team with the participation of the Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf (HZDR) has now developed a material system to generate terahertz pulses much more effectively than before. It is based on graphene, i.e., a super-thin carbon sheet, coated with a metallic lamellar structure. The research group presented its results in the journal ACS Nano.

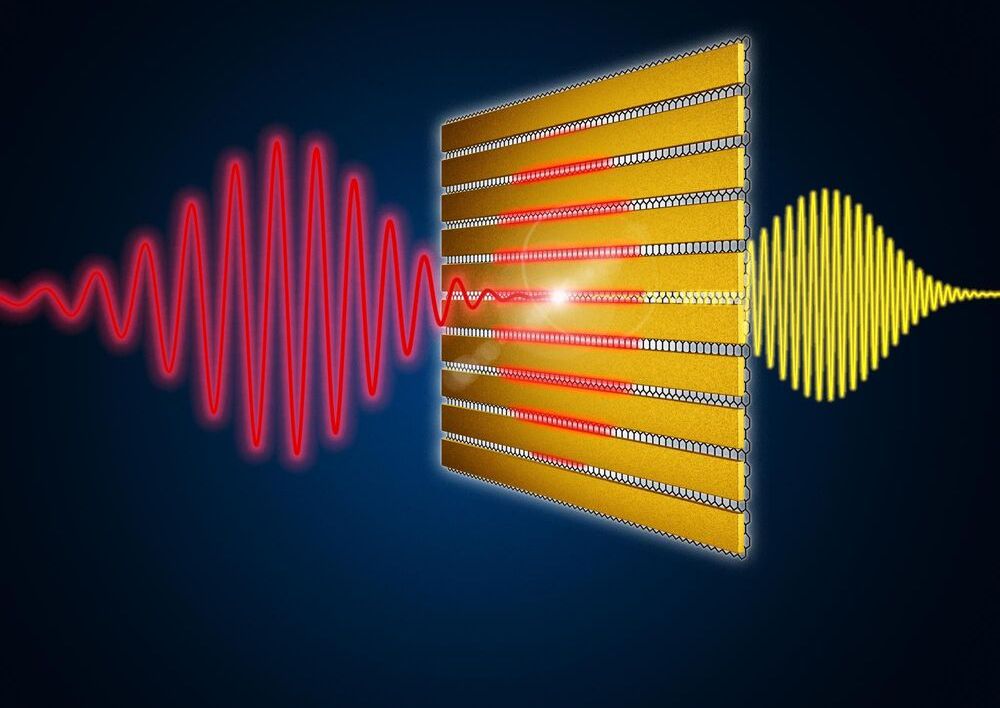

Some time ago, a team of experts working on the HZDR accelerator ELBE were able to show that graphene can act as a frequency multiplier: When the two-dimensional carbon is irradiated with light pulses in the low terahertz frequency range, these are converted to higher frequencies. Until now, the problem has been that extremely strong input signals, which in turn could only be produced by a full-scale particle accelerator, were required to generate such terahertz pulses efficiently.“This is obviously impractical for future technical applications,” explains the study’s primary author Jan-Christoph Deinert of the Institute of Radiation Physics at HZDR. “So, we looked for a material system that also works with a much less violent input, i.e., with lower field strengths.”

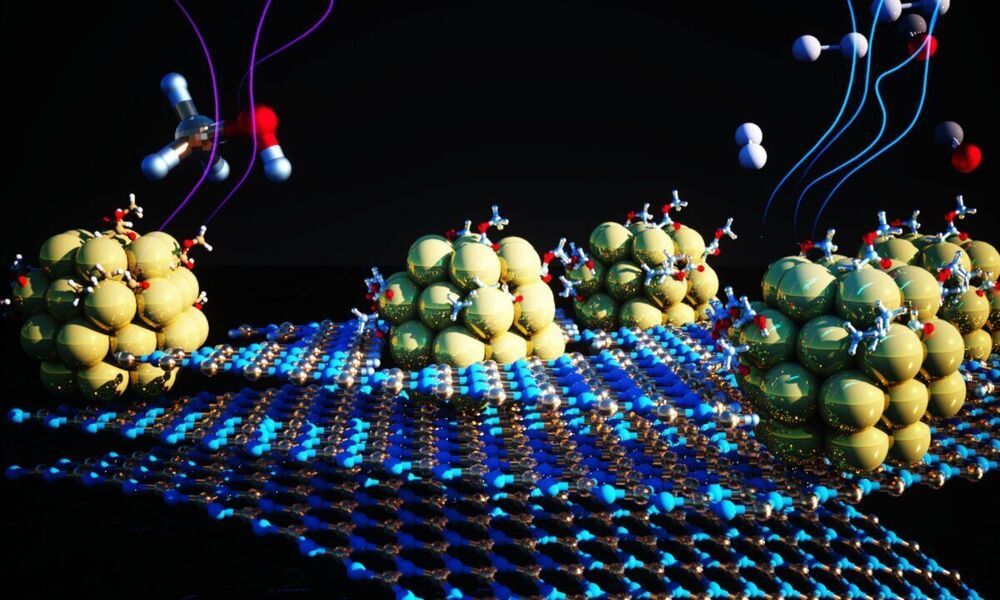

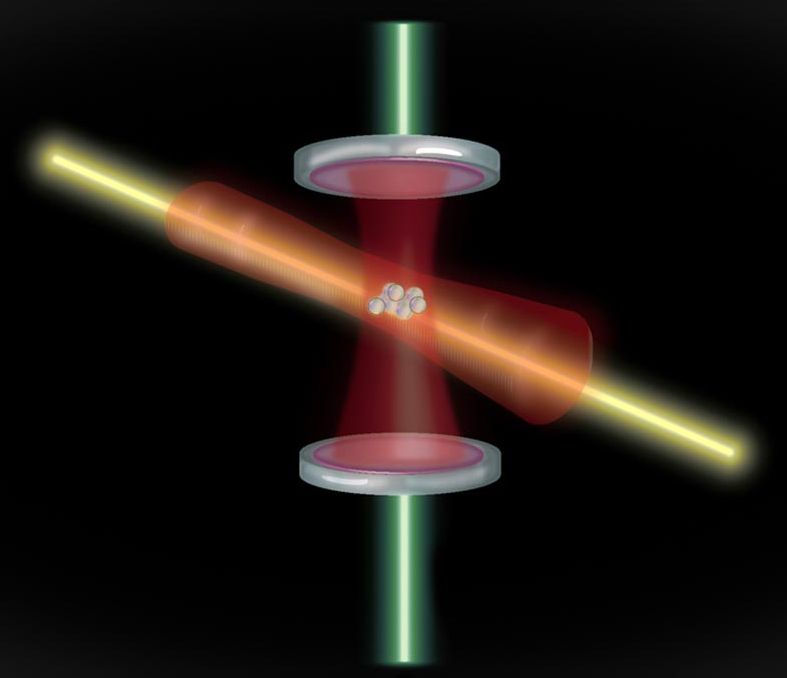

For this purpose, HZDR scientists, together with colleagues from the Catalan Institute of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology (ICN2), the Institute of Photonic Sciences (ICFO), the University of Bielefeld, TU Berlin and the Mainz-based Max Planck Institute for Polymer Research, came up with a new idea: the frequency conversion could be enhanced enormously by coating the graphene with tiny gold lamellae, which possess a fascinating property: “They act like antennas that significantly amplify the incoming terahertz radiation in graphene,” explains project coordinator Klaas-Jan Tielrooij from ICN2. “As a result, we get very strong fields where the graphene is exposed between the lamellae. This allows us to generate terahertz pulses very efficiently.”