But Moscow warns against insisting on including China in New Start negotiations.

University researchers have discovered that quantum communications are possible with submerged objects in turbulent water. The revelation means it might someday be possible for the National Command Authority to use quantum communications to securely communicate with underwater submarines, particularly those that make up part of the nuclear triad.

China might be secretly conducting nuclear tests with very low explosive power despite Beijing’s assertions that it is strictly adhering to an international accord banning all nuclear tests, according to a new arms-control report to be made public by the State Department.

The coming report doesn’t present proof that China is violating its promise to uphold the agreement, but it cites an array of activities that “raise concerns” that Beijing might not be complying with the “zero-yield” nuclear-weapons testing ban.

As the world fights against the COVID-19 pandemic, nuclear weapons have taken a backseat in most people’s minds. But for Global Strike Command (AFGSC)—the Air Force unit in control of two of the three legs of America’s nuclear triad—their mission remains top priority.

And it’s an unforgiving business. Nuclear deterrence requires extreme levels of readiness among pilots, maintenance crews, and security teams. Adversaries that don’t think the U.S. can respond with conventional bombing strikes or nukes could be emboldened to act aggressively.

But in a War of the Worlds-style twist, humanity’s most lethal weapons could be nullified by an organism that can’t even be seen. It’s up to the AFGSC to make sure that never happens.

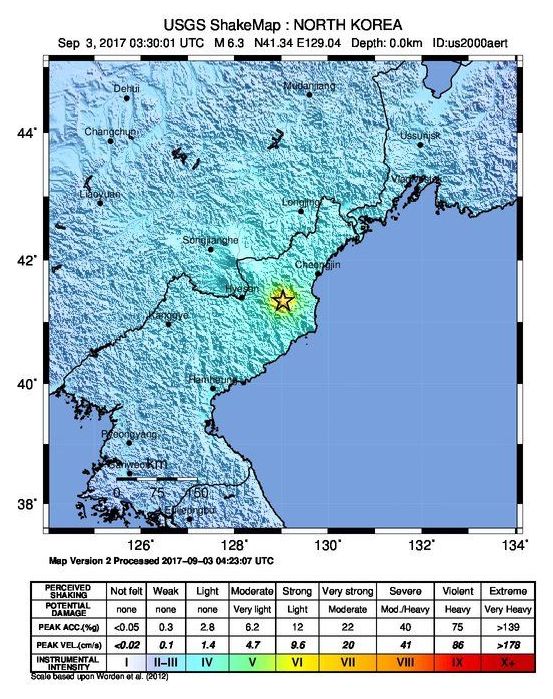

North Korea conducted its sixth nuclear test on 3 September 2017, stating it had tested a thermonuclear weapon (hydrogen bomb).[6].

A new look at 2017 test data reveals an explosion 16 times as powerful than the one that leveled Hiroshima.

Scientists looking anew at a 2017 North Korean nuclear test discovered that the explosion was likely about two-thirds more powerful than U.S. officials previously thought.

Earlier data put the yield somewhere between 30 and 300 kilotons; the U.S. intelligence community said 140 kilotons. That was already the most powerful device tested by North Korea, topping a 2016 test by about an order of magnitude. But a new look at seismological data suggests that the blast was between 148 and 328 kilotons, and probably around 250 kilotons.

Just days after North Korea announced it was suspending its testing programme, scientists revealed that the country’s underground nuclear test site had partially collapsed. This assessment was based on data gathered from smaller earthquakes that followed North Korea’s biggest nuclear test in 2017. A new study published in Science has now confirmed the collapse using satellite radar imaging.

The collapse may have played a role in North Korea’s change in policy. If correct, and with the hindsight of this research, we might have speculated that the North Koreans would want to make such an offer of peace. This shows how scientific analysis normally reserved for studying natural earthquakes can be a powerful tool in deciphering political decisions and predicting future policy across the globe.

In fact, another unusual earthquake in South Korea in 2017 also has the potential to affect geopolitics, this time by changing energy policy. “Seismic shift” may be a cliche often used by journalists and policymakers to describe changing political landscapes, but these recent earthquakes along the Korean Peninsula remind us there can really be authentic links between seismic events and global affairs.