Interesting.

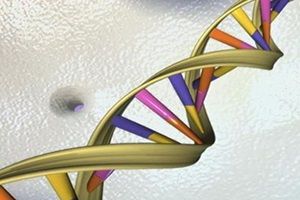

WHAT: Scientists at the National Institutes of Health are reporting new, unexpected details about the fundamental structure of collagen, the most abundant protein in the human body. In lab experiments, they demonstrated that collagen, once viewed as inert, forms structures that regulate how certain enzymes break down and remodel body tissue. The finding of this regulatory system provides a molecular view of the potential role of physical forces at work in heart disease, cancer, arthritis, and other disease-related processes, they say. The study appears in the current online issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Scientists have known for years that collagen remodeling plays an important role in a wide variety of biological processes ranging from wound healing to cancer growth. In particular, researchers know that collagen is broken down by a certain class of enzymes called matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), but exactly how they did this remained somewhat of a mystery, until now.

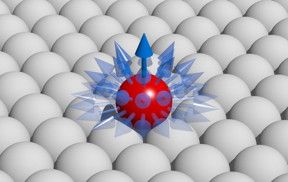

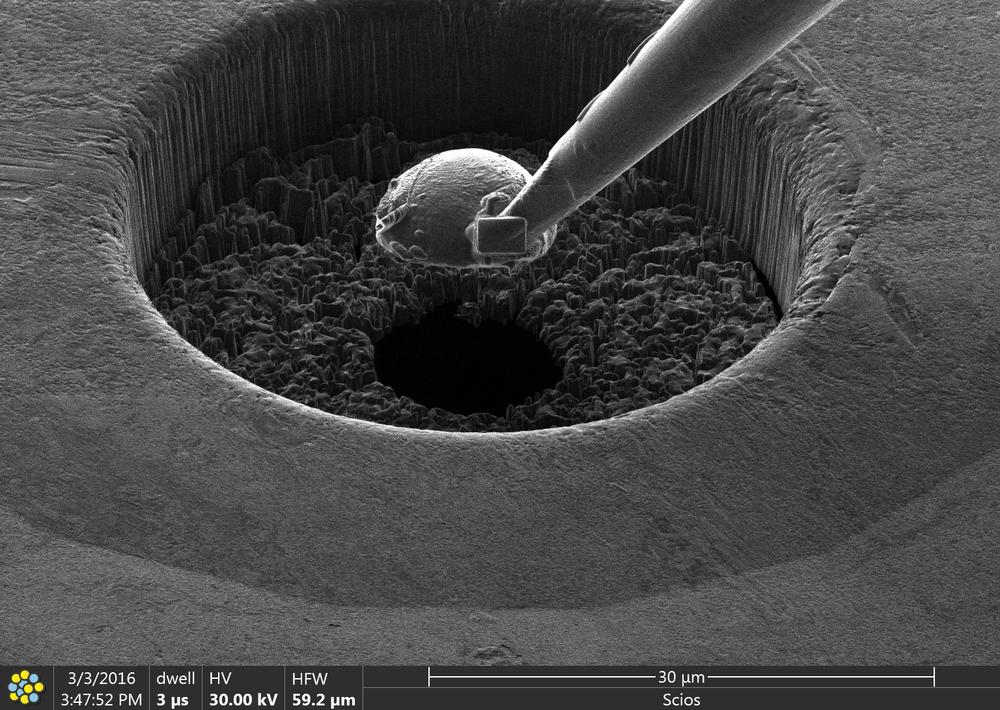

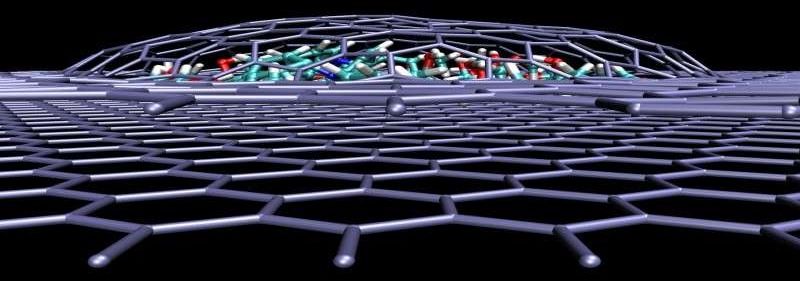

In the NIH study, the scientists isolated individual, nano-sized collagen fibrils from rat-tail tendons. They then exposed the collagen fibrils to fluorescently-labeled human MMP enzymes. Using video microscopy, the scientists tracked thousands of enzymes moving along a fibril. Unexpectedly, the scientists observed that the enzymes preferred to attach at certain sites along the fibril, and over time these attachment sites slowly moved, or disappeared and reappeared in other positions. These observations revealed collagen fibrils have defects that spontaneously form and heal. In the presence of tension, such as when tendons stretch, defects are likely eliminated, preventing enzymes from breaking down collagen that is loaded by physical force, the researchers suggest. In short, they identified a possible strain-sensitive mechanism for regulating tissue remodeling.