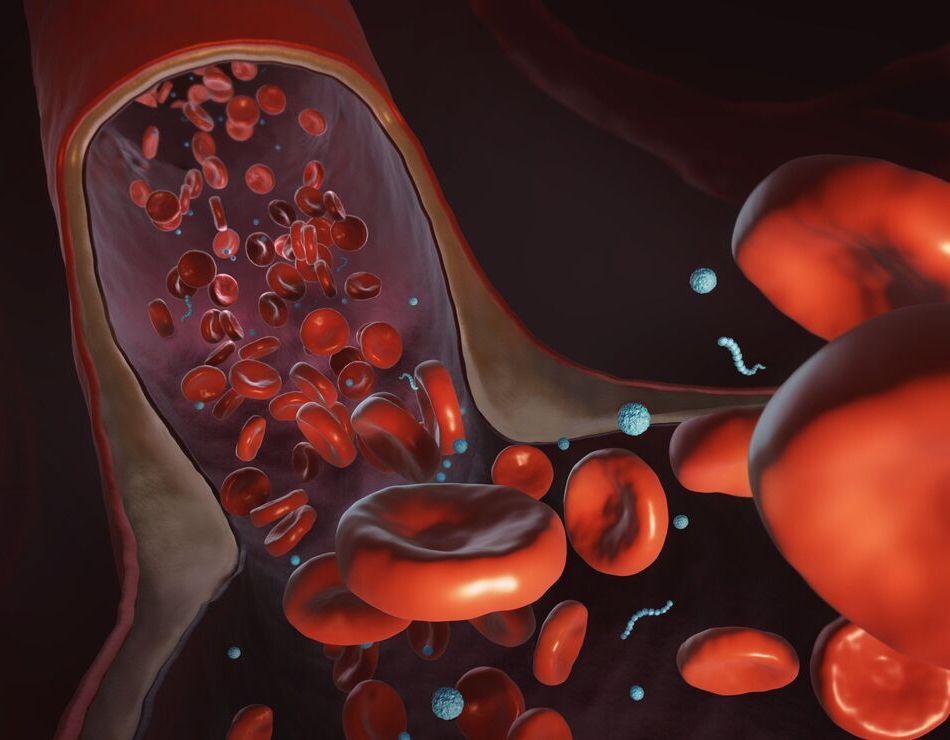

Influenza, commonly known as the flu virus, places a substantial burden on public health in the United States. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that influenza has resulted in about 9 million to 45 million diseases, 140000 to 810000 hospitalizations, and 12000 to 61000 deaths each year over the past decade.

Though flu vaccines are readily available to the public, they need to be remodeled and administered every year to combat new viral variants, which can undermine vaccine efficacy. Because of this, scientists have aimed to develop a universal vaccine that can protect against all influenza strains, and that can last for many years.

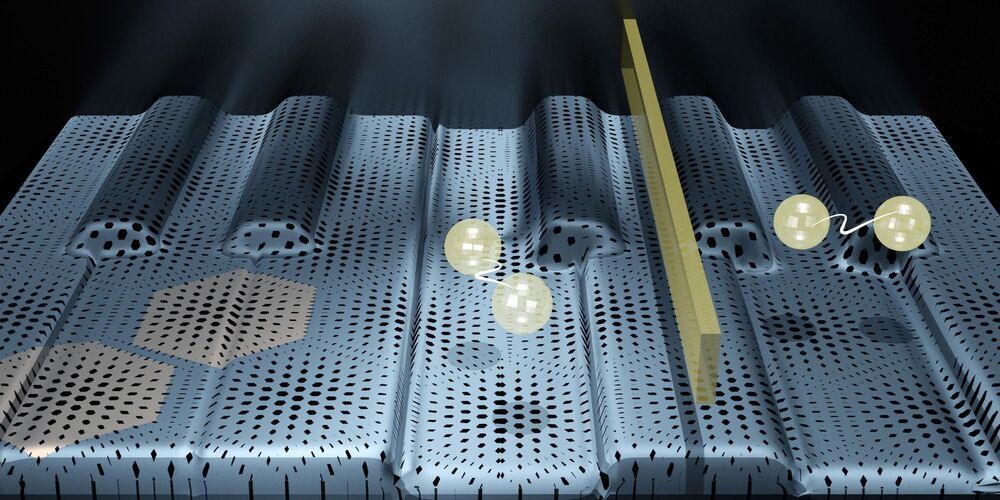

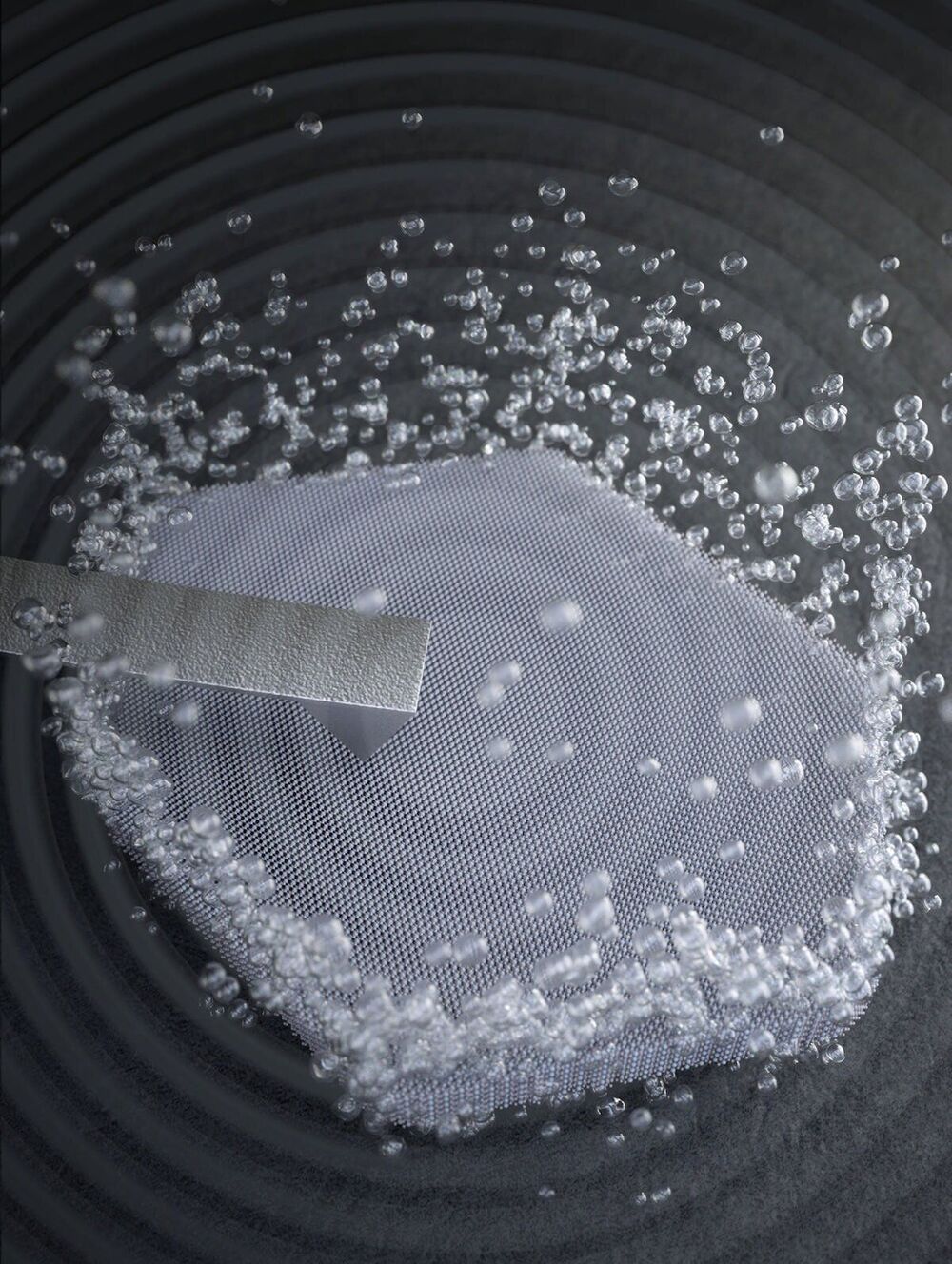

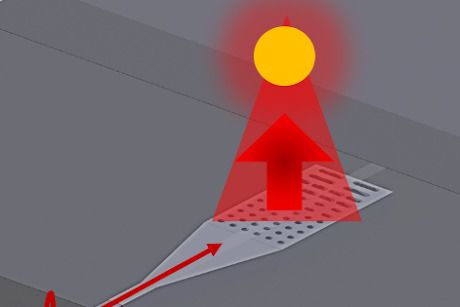

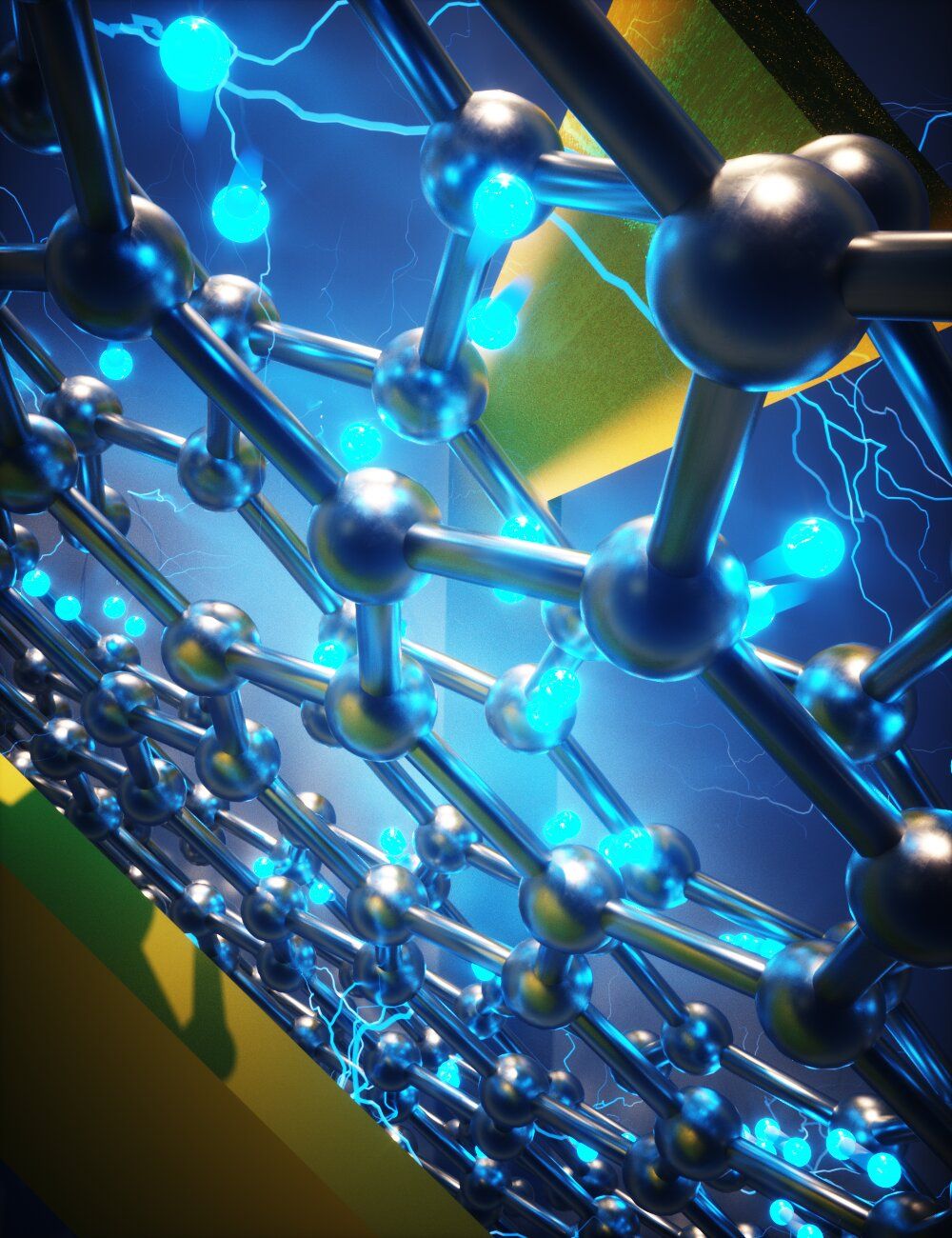

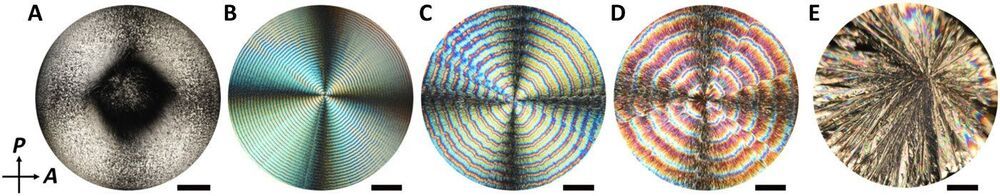

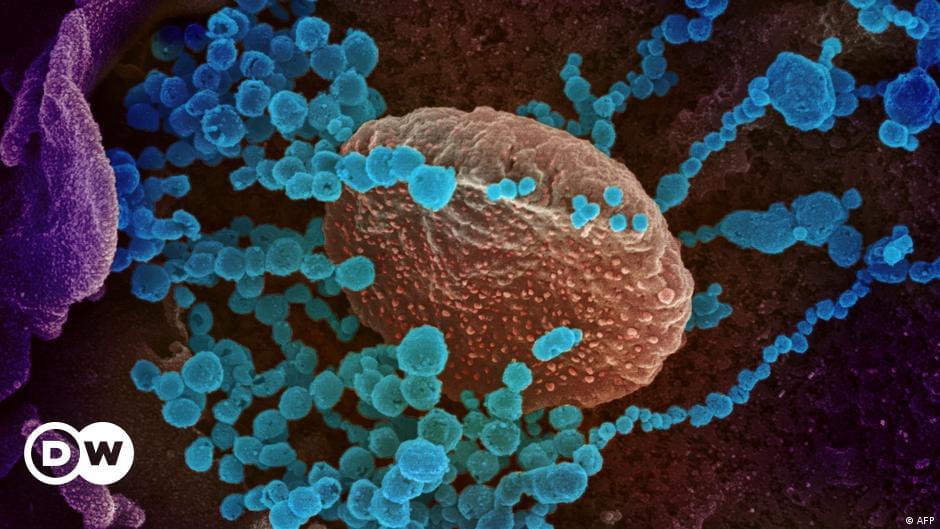

Now, researchers at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)’s Vaccine Research Center (VRC) and the University of Washington School of Medicine’s Institute for Protein Design (IPD) developed a universal flu vaccine candidate using small particles (nanoparticles), which can induce a long-lasting immune response.