Dr. Nick Melosh at the BrainMind Summit hosted at Stanford, interviewed by BrainMind member Christian Bailey.

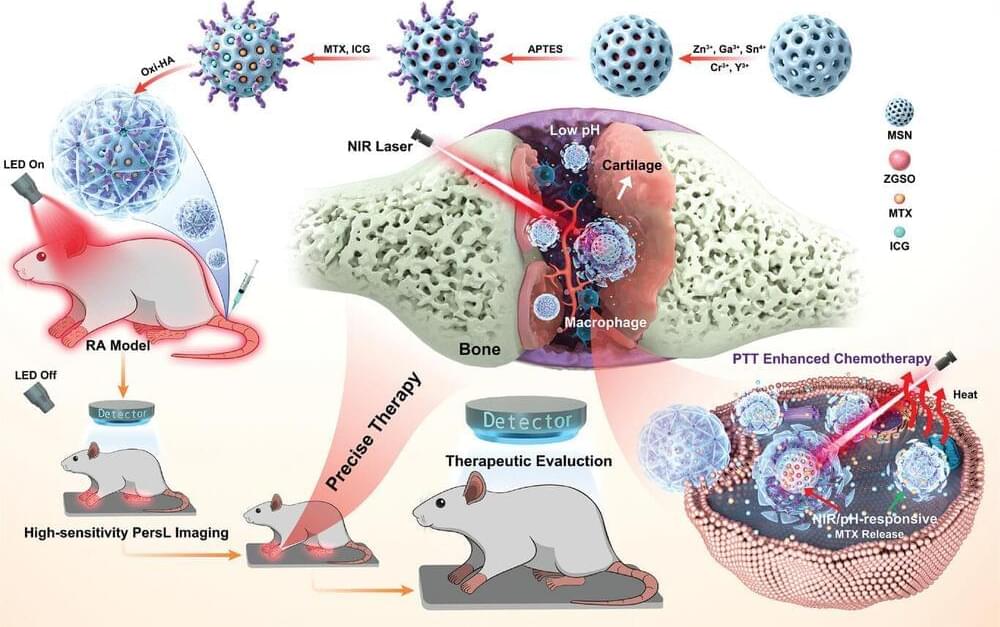

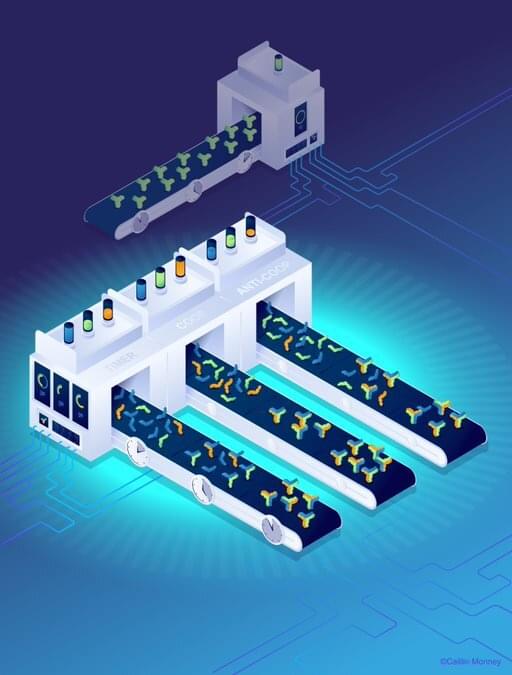

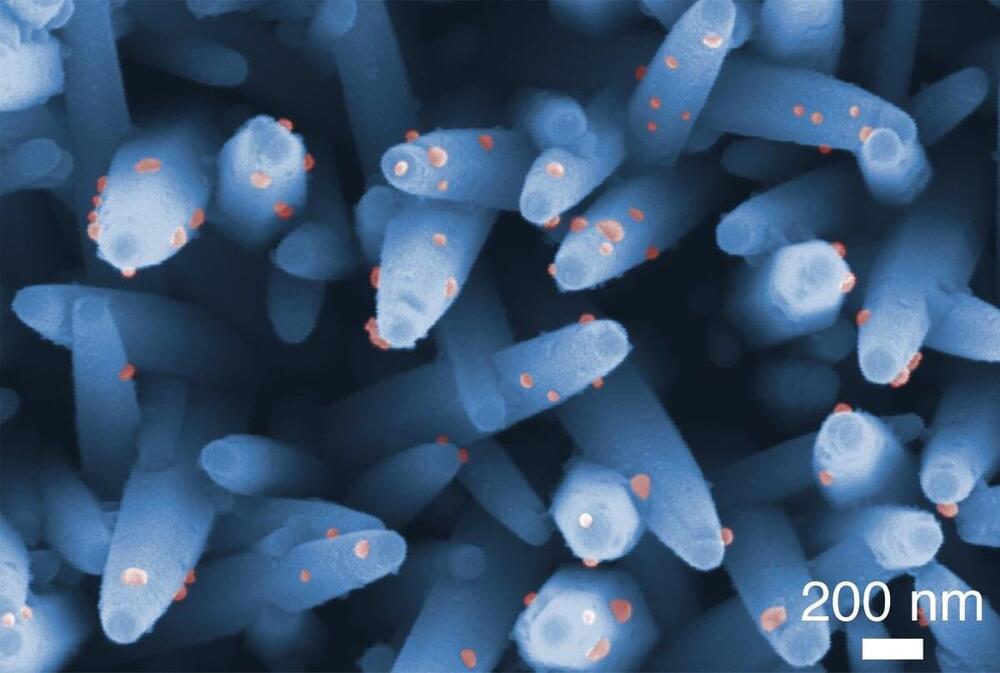

Nick Melosh is a Professor of Materials Science and Engineering, Stanford University. Nick’s research at Stanford focuses on how to design new inorganic structures to seamlessly integrate with biological systems to address problems that are not feasible by other means. This involves both fundamental work such as to deeply understand how lipid membranes interact with inorganic surfaces, electrokinetic phenomena in biologically relevant solutions, and applying this knowledge into new device designs. Examples of this include “nanostraw” drug delivery platforms for direct delivery or extraction of material through the cell wall using a biomimetic gap-junction made using nanoscale semiconductor processing techniques. We also engineer materials and structures for neural interfaces and electronics pertinent to highly parallel data acquisition and recording. For instance, we have created inorganic electrodes that mimic the hydrophobic banding of natural transmembrane proteins, allowing them to ‘fuse’ into the cell wall, providing a tight electrical junction for solid-state patch clamping. In addition to significant efforts at engineering surfaces at the molecular level, we also work on ‘bridge’ projects that span between engineering and biological/clinical needs. My long history with nano-and microfabrication techniques and their interactions with biological constructs provide the skills necessary to fabricate and analyze new bio-electronic systems.”

Learn more about BrainMind: https://brainmind.org/

Apply to BrainMind: https://brainmind.org/application