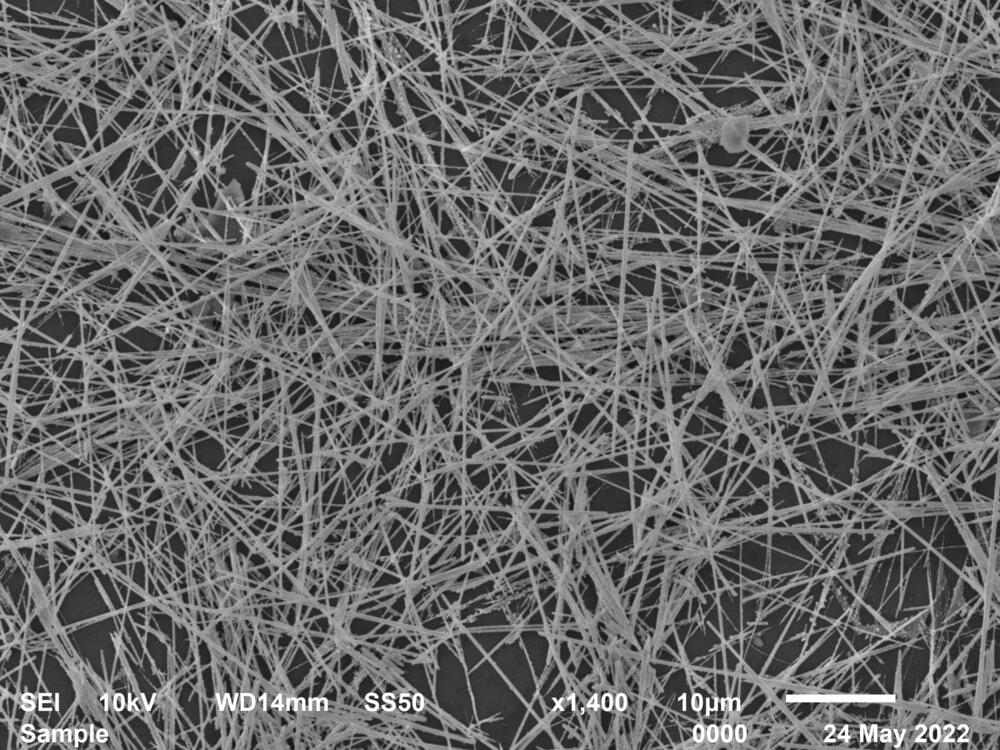

A tangle of silver nanowires may pave the way to low-energy real-time machine learning.

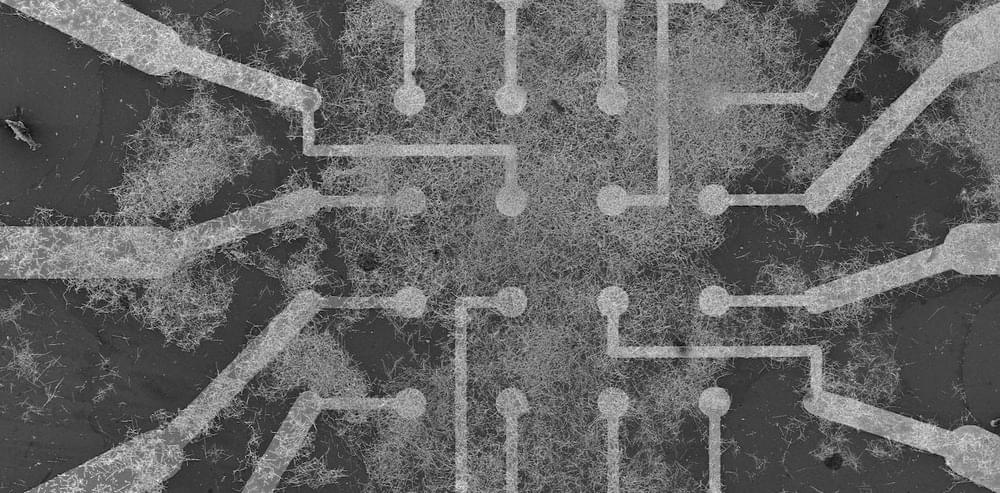

MIT physicists and colleagues have metaphorically turned graphite, or pencil lead, into gold by isolating five ultrathin flakes stacked in a specific order. The resulting material can then be tuned to exhibit three important properties never before seen in natural graphite.

“It is kind of like one-stop shopping,” says Long Ju, an assistant professor in the MIT Department of Physics and leader of the work, which is reported in the Nature Nanotechnology. “In this case, we never realized that all of these interesting things are embedded in graphite.”

Further, he says, “It is very rare to find materials that can host this many properties.”

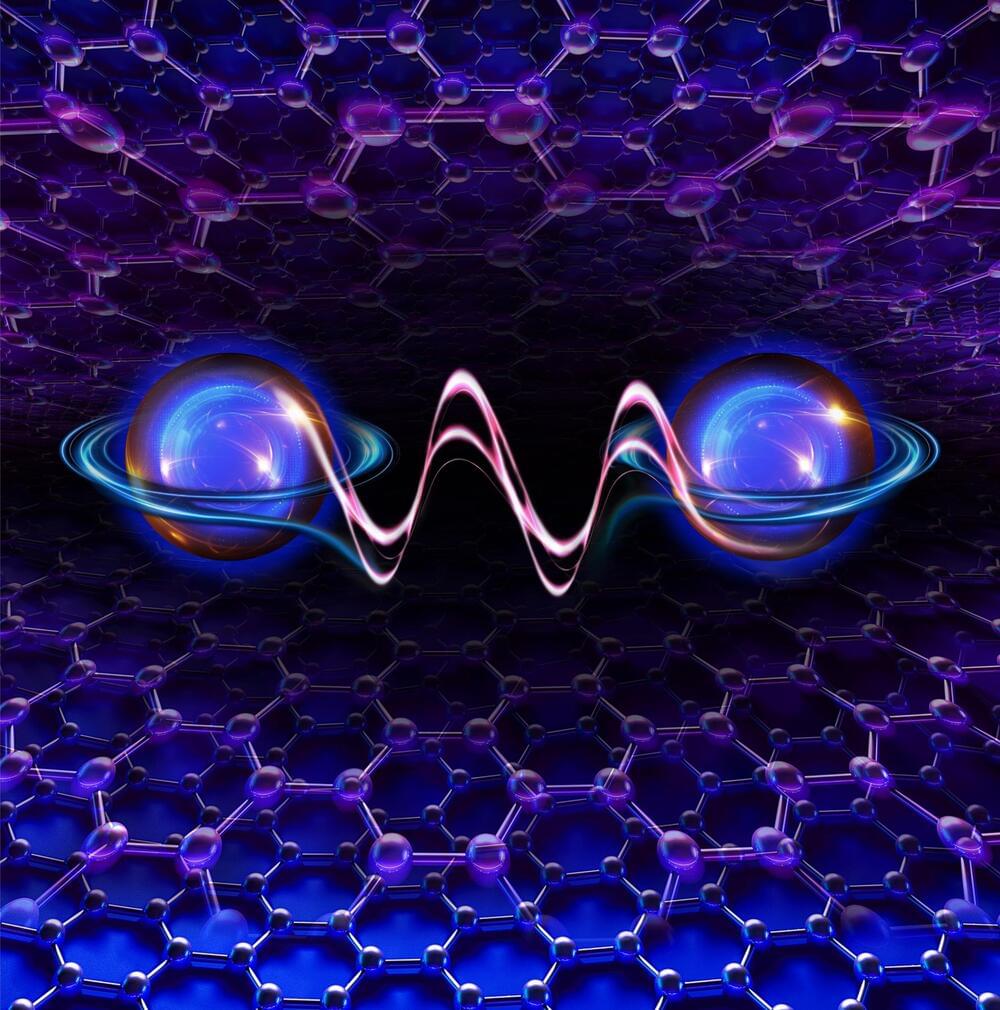

Surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) is a powerful fingerprint analysis and detection technique that plays an important role in the fields of food safety, environmental protection, bio-imaging and hazardous substance identification. Electromagnetic enhancement (EM) and chemical enhancement (CM) are the two recognized mechanisms of action for amplifying Raman signals.

EM originates from the localized surface plasmonic resonance effect of noble metal nanostructures such as gold, silver, and copper, while CM originates from the charge transfer between the substrate and the probe molecules. In principle, the charge transfer efficiency depends on the coupling of the incident laser energy to the energy levels of the substrate-molecule system.

Compared to EM-based SERS substrates, CM-based SERS substrates are usually made of two-dimensional materials including semiconductor oxides, metal carbides, and graphene and its evolutions, which have weaker signal enhancement capabilities. However, the advantages of CM-based SERS substrate, such as high specificity, homogeneity and biocompatibility, have attracted the attention of researchers.

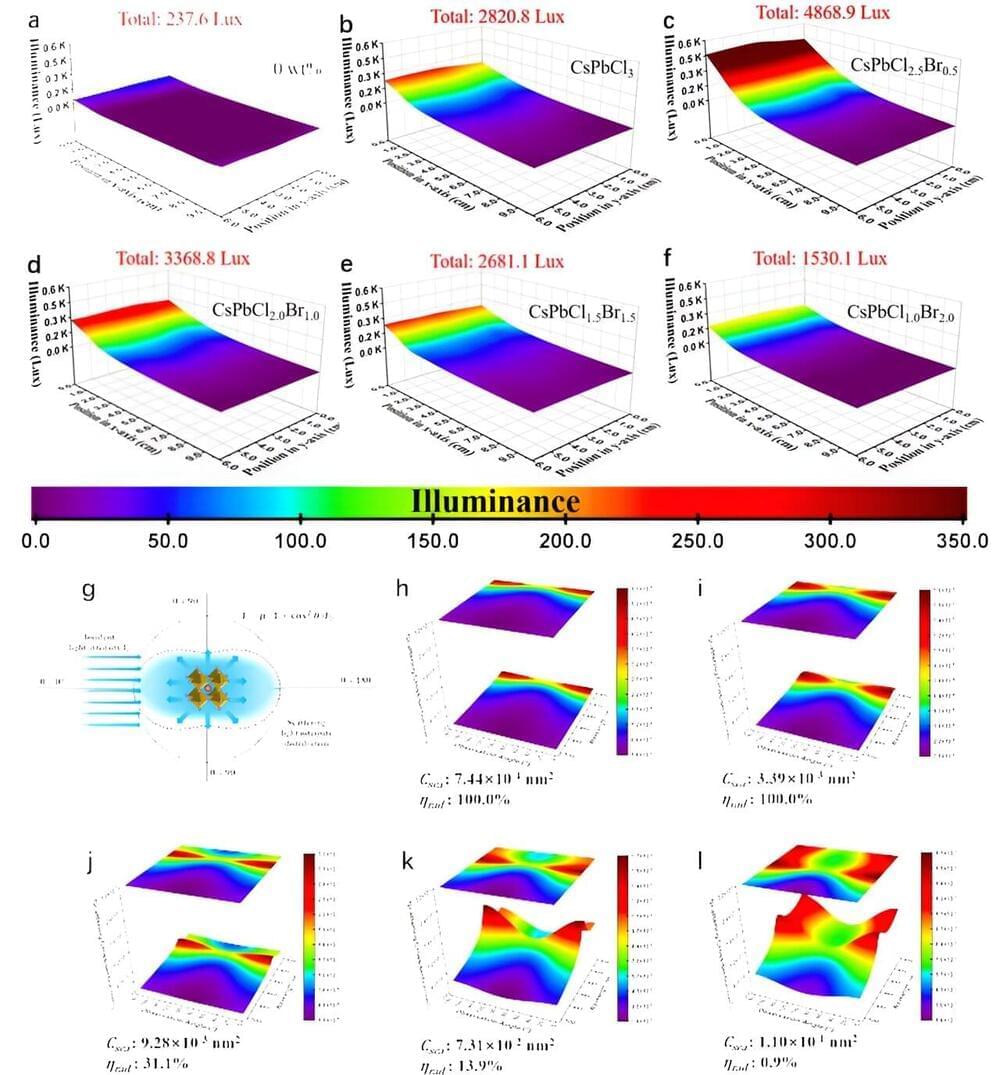

The fact that nanoparticle and polymer hybrid materials can often combine the advantages of each has been demonstrated in several fields. Embedding PNCs into polymer is an effective strategy to enhance the PNCs stability and polymer can endow the PNCs with other positive effects based on different structure and functional groups.

The uniform distribution of PNCs in polymer matrix is critical to the properties of the nanocomposites and the aggregation of PNCs induced by high surface energy has a severe influence on the performance of related applications. As such, the loading fraction is limited owing to the phase separation between PNCs and polymer.

Chemical interaction between PNCs and polymer is necessary to suppress the phase separation. Meanwhile, most of the fabrication methods of PNCs/polymer nanocomposites are spin coating, swelling-shrinking and electrospinning based on the in-situ synthesis of PNCs in polymer matrix and physical mixing, but extremely few works can achieve the fabrication of PNCs/polymer nanocomposites by bulk polymerization.

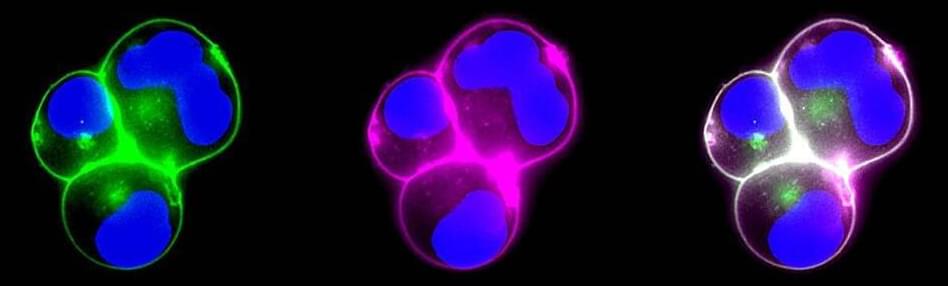

Despite exciting advances in gene editing, the efficient delivery of genetic tools to extrahepatic tissues remains challenging. This holds particularly true for the skin, which poses a highly restrictive delivery barrier. In this study, we ran a head-to-head comparison between Cas9 mRNA or ribonucleoprotein (RNP)-loaded lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) to deliver gene editing tools into epidermal layers of human skin, aiming for in situ gene editing. We observed distinct LNP composition and cell-specific effects such as an extended presence of RNP in slow-cycling epithelial cells for up to 72 h. While obtaining similar gene editing rates using Cas9 RNP and mRNA with MC3-based LNPs (10–16%), mRNA-loaded LNPs proved to be more cytotoxic. Interestingly, ionizable lipids with a p Ka ∼ 7.1 yielded superior gene editing rates (55%–72%) in two-dimensional (2D) epithelial cells while no single guide RNA-dependent off-target effects were detectable. Unexpectedly, these high 2D editing efficacies did not translate to actual skin tissue where overall gene editing rates between 5%–12% were achieved after a single application and irrespective of the LNP composition. Finally, we successfully base-corrected a disease-causing mutation with an efficacy of ∼5% in autosomal recessive congenital ichthyosis patient cells, showcasing the potential of this strategy for the treatment of monogenic skin diseases. Taken together, this study demonstrates the feasibility of an in situ correction of disease-causing mutations in the skin that could provide effective treatment and potentially even a cure for rare, monogenic, and common skin diseases.

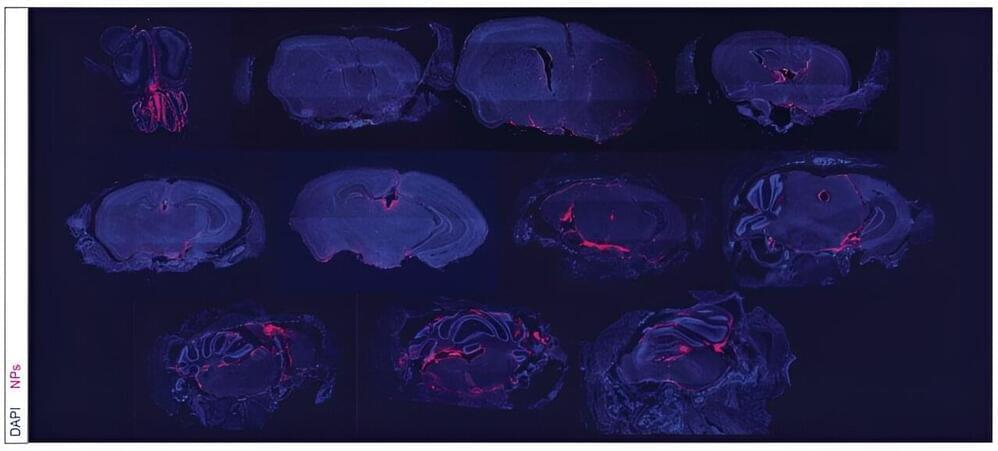

Using nanoparticles administered directly into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), a research team has developed a treatment that may overcome significant challenges in treating a particularly deadly brain cancer.

The researchers, led by professors Mark Saltzman and Ranjit Bindra, administered to mice with medulloblastoma a treatment that features specially designed drug-carrying nanoparticles. The study, published in Science Translational Medicine, showed that mice who received this treatment lived significantly longer than mice in the control group.

Medulloblastoma, a brain cancer that predominantly affects children, often begins with a tumor deep inside the brain. The cancer is prone to spread along two protective membranes known as the leptomeninges throughout the central nervous system, particularly the surface of the brain and the CSF.

Engineers at the University of California San Diego have developed modular nanoparticles that can be easily customized to target different biological entities such as tumors, viruses or toxins. The surface of the nanoparticles is engineered to host any biological molecules of choice, making it possible to tailor the nanoparticles for a wide array of applications, ranging from targeted drug delivery to neutralizing biological agents.

The beauty of this technology lies in its simplicity and efficiency. Instead of crafting entirely new nanoparticles for each specific application, researchers can now employ a modular nanoparticle base and conveniently attach proteins targeting a desired biological entity.

In the past, creating distinct nanoparticles for different biological targets required going through a different synthetic process from start to finish each time. But with this new technique, the same modular nanoparticle base can be easily modified to create a whole set of specialized nanoparticles.

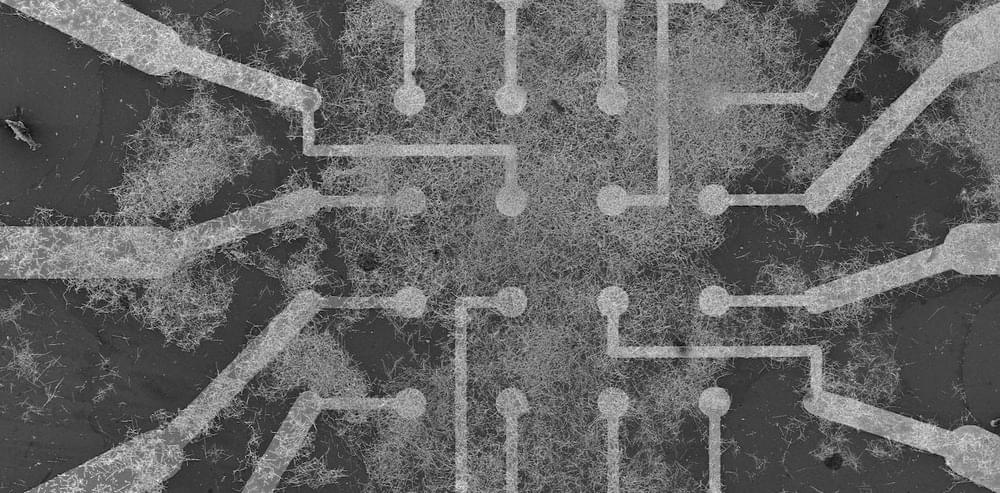

For the first time, a physical neural network has successfully been shown to learn and remember “on the fly,” in a way inspired by and similar to how the brain’s neurons work.

The result opens a pathway for developing efficient and low-energy machine intelligence for more complex, real-world learning and memory tasks.

Published today in Nature Communications, the research is a collaboration between scientists at the University of Sydney and University of California at Los Angeles.

Nanotechnology sounds like a futuristic development, but we already have it in the form of CPU manufacturing. More advanced nanotech could be used to create independent mobile entities like nanobots. One of the main challenges is selecting the right chemicals, elements, and structures that actually perform a desired task. Currently, we create more chemically oriented than computationally oriented nanobots, but we still have to deal with the quantum effects at tiny scale.

One of the most important applications of nanotechnology is to create nanomedicine, where the technology interacts with biology to help resolve problems. Of course, the nanobots have to be compatible with the body (e.g. no poisonous elements if they were broken down, etc).

We dive into an interesting study on creating nanobarrels to deliver a particular payload within the bloodstream (currently in animals, but eventually in humans). This study is able to deliver RNA to cancer cells that shuts them down, without affecting the rest of the body. This type of application is why the market for nanotechnology keeps growing and will have a substantial impact on medicine in the future.

#nanotech #nanobots #medicine.

DNA origami nanobots – The University of Sydney Nano Institute.

https://www.sydney.edu.au/nano/our-research/research-program…obots.html.

ASU scientists have successfully programmed nanorobots to shrink tumors by cutting off their blood supply.

The convergence of Biotechnology, Neurotechnology, and Artificial Intelligence has major implications for the future of humanity. This talk explores the long-term opportunities inherent to these fields by surveying emerging breakthroughs and their potential applications. Whether we can enjoy the benefits of these technologies depends on us: Can we overcome the institutional challenges that are slowing down progress without exacerbating civilizational risks that come along with powerful technological progress?

About the speaker: Allison Duettmann is the president and CEO of Foresight Institute. She directs the Intelligent Cooperation, Molecular Machines, Biotech & Health Extension, Neurotech, and Space Programs, Fellowships, Prizes, and Tech Trees, and shares this work with the public. She founded Existentialhope.com, co-edited Superintelligence: Coordination & Strategy, co-authored Gaming the Future, and co-initiated The Longevity Prize. She advises companies and projects, such as Cosmica, and The Roots of Progress Fellowship, and is on the Executive Committee of the Biomarker Consortium. She holds an MS in Philosophy & Public Policy from the London School of Economics, focusing on AI Safety.