In summary — “I am cautiously optimistic about the promise of tDCS; cognitive training paired with tDCS specifically could lead to improvements in attention and memory for people of all ages and make some huge changes in society. Maybe we could help to stave off cognitive decline in older adults or enhance cognitive skills, such as focus, in people such as airline pilots or soldiers, who need it the most. Still, I am happy to report that we have at least moved on from torpedo fish” smile

In 47 CE, Scribonius Largus, court physician to the Roman emperor Claudius, described in his Compositiones a method for treating chronic migraines: place torpedo fish on the scalps of patients to ease their pain with electric shocks. Largus was on the right path; our brains are comprised of electrical signals that influence how brain cells communicate with each other and in turn affect cognitive processes such as memory, emotion and attention.

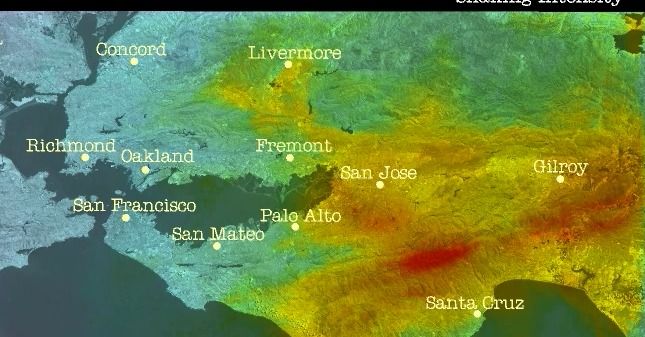

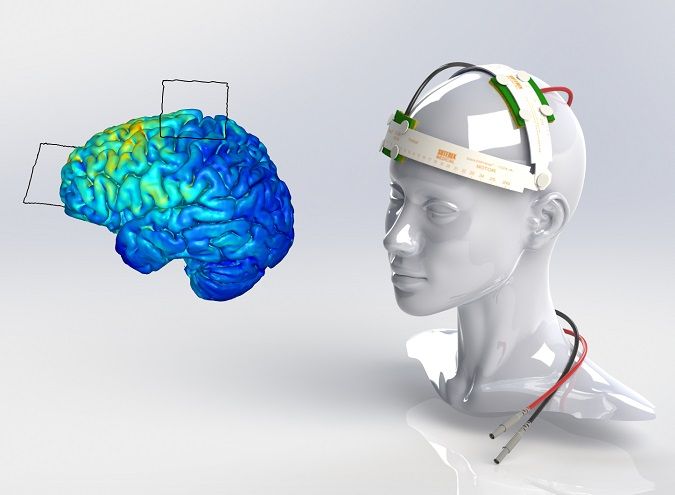

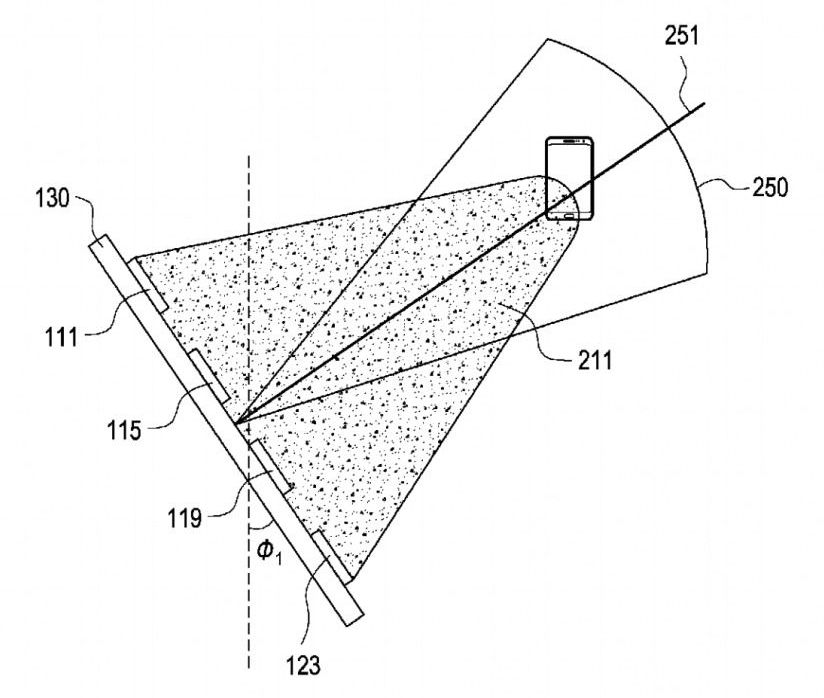

The science of brain stimulation – altering electrical signals in the brain – has, needless to say, changed in the past 2,000 years. Today we have a handful of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) devices that deliver constant, low current to specific regions of the brain through electrodes on the scalp, for users ranging from online video-gamers to professional athletes and people with depression. Yet cognitive neuroscientists are still working to understand just how much we can influence brain signals and improve cognition with these techniques.

Brain stimulation by tDCS is non-invasive and inexpensive. Some scientists think it increases the likelihood that neurons will fire, altering neural connections and potentially improving the cognitive skills associated with specific brain regions. Neural networks associated with attention control can be targeted to improve focus in people with attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Or people who have a hard time remembering shopping lists and phone numbers might like to target brain areas associated with short-term (also known as working) memory in order to enhance this cognitive process. However, the effects of tDCS are inconclusive across a wide body of peer-reviewed studies, particularly after a single session. In fact, some experts question whether enough electrical stimulation from the technique is passing through the scalp into the brain to alter connections between brain cells at all.